By now I know all the tricks of my morning bus commute: Walk a few blocks out of the way to another stop in order to grab a seat before the bus gets full (which it always does). If the bus is already packed to the gills (which it sometimes is), hover over someone sitting down who might get off the bus soon. Don’t do it menacingly, but subtly let others know that if this person gets off the bus, that seat will be mine, suckers! Hey, it’s a dog-eat-dog world out there in the land of public transportation.

And here in Seattle, it’s about to get worse. Our bus provider, Metro, faces an ongoing budget gap of $75 million and, if we can’t find a way to close that gap, it will cut at least 72 routes starting in the fall. With the completion of a light-rail extension still years away, commuters who rely on public transportation here will find themselves stuck between a rock and a hard place, much like a certain tunneling machine in another ill-conceived Seattle transportation plan fail.

Like a lot of other cities in this country, Seattle’s public transportation story is a sad tale of post-recession budget shortfalls, outdated urban planning, and a not-so-efficient bus system with a PR problem. And like a lot of other cities, its problems run deeper than just figuring out how to keep the buses running.

But Seattle might be the city that’s tried just about everything to avoid bus service cuts (so far). First there was Plan A: The state legislature would vote to provide funding. FAIL! As in other states, the legislature has not been keen to support the transit plans of cities.

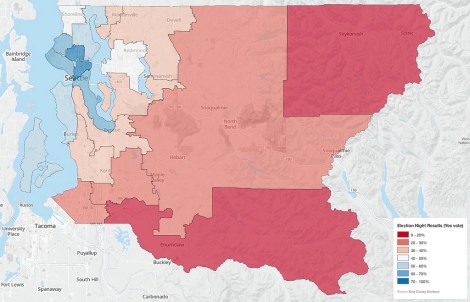

Then came Plan B: Prop 1, a county-wide, mid-year ballot measure that sought to fund the ailing Metro service by charging $60 “tabs” for cars in the metro area. The measure passed 2-to-1 in the city, but failed spectacularly in the surrounding suburbs, as you can see from the map below. The blue shades, which are mostly urban areas, show where people voted to save Metro bus service. The red shades show the surrounding suburbs where the measure was not supported (click here for the full interactive version).

Click to embiggen.Oran Viriyincy

After Prop 1 tanked, transit advocates started gathering signatures for what became known as Plan C, an initiative that would hike property taxes to prevent bus cuts — but only in the city proper. All those suburbanites who voted against the car tabs can sit in traffic and choke on their own exhaust fumes.

But at a press conference last week, Mayor Ed Murray warned that if Seattle becomes “the Lone Ranger on transit,” the city risks “the Balkanization of Metro,” isolating the city from the surrounding region. “We don’t live in a hobbit village,” he said. “Tens of thousands of people leave Seattle every day to go to work and tens of thousands of people come from outside Seattle to go to work.”

Murray has promised to put yet another plan on the ballot in November – one that would create a car tab, like Prop 1, but this time it’s for Seattle city residents only. Unlike Plan C, however, Murray’s proposal would keep bus service running to the suburbs with a regional transit fund. He sees it as a short-term fix. Since a lot of folks here in The Shire Seattle proper consider public bus access our precious, we can support service to the ‘burbs until residents there can be convinced to pitch in.

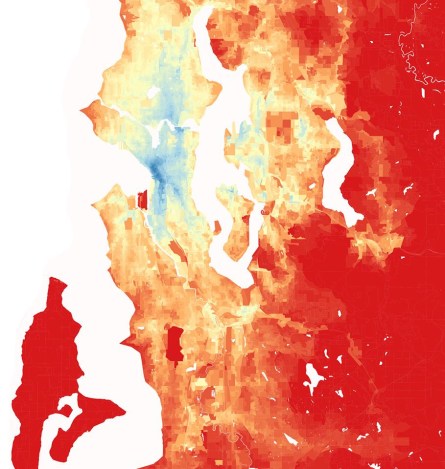

Well, that’s awfully nice of us. But there’s a reason suburbanites don’t like to pay for public transit: It doesn’t work well for them. The map below plots the total number of jobs accessible within 1 hour on our existing public transit starting at 7:00 a.m. on a weekday. The dark blue shades show areas where you can reach about 500,000 jobs within an hour’s transit time. In the red areas have fewer than 10,000 transit-accessible jobs.

Click to embiggen.Brandon Martin-Anderson/Conveyal

Look familiar? The colors on this map line up pretty well with the results of the Prop 1 map. Double rainbow! What does it mean? Public transportation is just not a viable option for getting to and from work in the suburbs. No wonder suburbanites aren’t willing to support transit measures.

The thing is that, the way things stand right now, buses can’t really compete with cars. Without dedicated bus lanes, they fill up highway space just like everybody else (although certainly a lot less space than cars do). Buses aren’t as reliable and convenient as rails, which tend to be the more popular option in the suburbs. According to The Stranger, only 27.2 percent of voters in suburban Kent wanted to save Metro bus service in April’s prop 1 vote, but 50.8 percent voted for funding the light rail in 2008.

So what can a straphanger-filled, cash-strapped municipality do to strike a healthy public transportation balance between the city and the suburbs? There’s a number of ways to go that don’t involve taxes or car tabs. One option is to bring back the “employee hours tax,” which offers businesses tax deductions for employees who do not commute to work in a single-occupancy vehicle. And there are many ways to encourage carpooling. (Chances are that the only point of tension among carpooling Seattle commuters would be which NPR station to listen to.)

Bus systems can also be retrofitted to serve the ‘burbs better. Grand Rapids, Mich., just launched the Silver Line, a “bus rapid transit” solution that functions like a light rail, with hybrid-electric buses that offer suburban commuters a straight shot into and out of downtown during peak rush hours on two designated bus lanes. Riders ditch the boarding lines with an honor system, and these ‘smart’ buses can even GPS their location to traffic lights so that they get a green light when behind schedule. (Seattle tried a less ambitious version of this kind of express bus service called RapidRide, but the restructuring efforts around it may have done more harm than good for some neighborhoods.) And the best part is the Silver Line was not funded by local dollars, but instead by a hefty Federal Transit Administration grant and state department of transportation money set aside for transit.

Seattle transit activist Ben Schiendelman from Keep Seattle Moving says that ultimately, this may be more a crisis of land-use than one of transportation. “King County Council was responsible for most of the zoning and initial construction in a lot of the places where Prop 1 failed hard,” says. “They allowed only one or two houses per acre — construction that’s totally highway dependent — and so the people who live there don’t see any benefit from transit. Once the highway gets built, it’s in your best interest to use it.”

So now that the highway’s already here, will it be used by buses or more cars? Seattle voters will decide in November.