The ever-thought-provoking David Levinson posed a question at his Transportationist blog that’s worth a longer look: Are you more likely to die from being in a car crash or from breathing in car emissions? If your gut reaction is like mine, then you’ve already answered in favor of crashes. But when you really crunch the numbers, the question not only becomes tougher to answer, it raises important new questions of its own.

First, let’s look at U.S. traffic fatalities at the national level. For consistency with the pollution statistics (more on that in a moment), we’ll focus on 2005. That year, there were 43,510 traffic crash fatalities in the United States, according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. That’s a fatality rate of roughly 14.7 per 100,000 Americans.

Now we turn to deaths attributable to air pollution — more specifically, to particulate matter produced by cars. A research team led by Fabio Caiazzo of MIT, who appears from his university profile to be an actual rocket scientist, recently quantified the impact of air pollution and premature death in the United States for the year 2005. They reported that about 52,800 deaths were attributable to particulate matter from road transportation alone. (Road pollution had the largest share of any individual pollution sector, at around a quarter of all emissions-related deaths.) That’s a mortality rate of roughly 17.9 per 100,000 Americans.

By that estimate, road-related particulate matter was responsible for about 19 percent more deaths, nationwide, than car crashes were in 2005. And keep in mind that particulate matter isn’t the only air pollutant produced by cars (though it is the most significant type). Caiazzo and company attribute another 5,250 annual deaths to road-related ozone concentrations, for instance. In other words, the true health impact of auto emissions may be much greater.

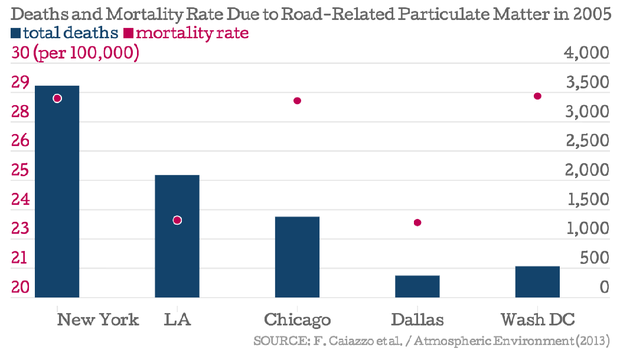

At the city level, this broad conclusion remains the same. Here are the mortality totals and rates attributable to road-related particulate matter in five major metro areas tracked by Caiazzo and colleagues: New York (3,615 / 28.5), Los Angeles (2,092 / 23.3), Chicago (1,379 / 28.4), Dallas (374 / 23.2), Washington, D.C. (533 / 28.6). The rates are well over 20 per 100,000 people in all five places.

CityLab

Now here are the fatality totals and rates from car crashes in the same five metros, via the Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Granted, these figures are from 2009 instead of 2005, but even taking that inconsistency into account, the difference is striking: New York (986 / 5.1), Los Angeles (848 / 6.6), Chicago (565 / 5.9), Dallas (611 / 9.8), Washington, D.C. (408 / 7.5). In no case does the fatality rate even reach double digits.

These straight fatality figures make a strong case that car emissions are deadlier than car crashes at both the national and major metro levels. But death is only one measure of these health impacts. Age of death matters, too, especially since younger people tend to be involved in fatal car crashes. In 2012, for instance, about 55 percent of the people who suffered motor fatalities were under age 45. Caiazzo et al. report that emissions tend to cut lives short about 12 years, whereas crashes cut them short about 35 years.

Levinson tries to adjust for age through the Global Burden of Disease database, which includes a measure called Years of Life Lost. In 2010, there were 1,641,050 years of life lost attributable to particulate matter, against 1,873,160 years of life lost to road injuries.

That might seem like a near wash, but in fact the gap is much wider, because the these data reflect all air pollution, not just road-related air pollution. If we figure (based on Caiazzo*) that 25 percent of all deaths attributable to air pollution come via car emissions, then road injuries account for more than four times as many years of life lost as particulate matter from cars — 1,873,160 to 410,288.

Circling back to the original question, whether car crashes or auto emissions is deadlier, we find any answer requires additional parameters. Strictly speaking, Americans appear more likely to die from auto emissions. In terms of wasted life potential, crashes seem the bigger danger. If anything, the absence of a clear single answer is a revelation in itself, suggesting that the problems are more on par than we typically treat them.

So why don’t elected leaders pay as much attention to emissions-attributable deaths as they do to car fatalities? The answer no doubt has a lot to do with something Levinson’s University of Minnesota colleague, Julian Marshall, said during their discussion of the topic: “no death certificate says ‘air pollution’ as cause of death.” Rather, emissions are yet another risk factor and invisible killer in a world full of risk factors and invisible killers. As such they’re convenient (and perhaps even comforting) to ignore. A road death, meanwhile, is stark and tragic and undeniable — in political terms, a much stronger platform.

But what should cities do about it? Well, they can start by drawing more attention to the problem. A true Vision Zero campaign, for instance, would acknowledge that even a New York without road fatalities wouldn’t be a New York without car-related deaths and illnesses. (That’s not to criticize this initiative; just to make a point.) As a stronger step, cities can follow the likes of London, which recently announced an additional tax on emissions-heavy cars, and start charging these drivers the true cost of their social impact (or something closer to it). A few drivers can pay now, or general public health can pay later, but everyone pays eventually.

* It’s worth pointing out that the Caiazzo study and the GBD reach vastly different conclusions about how deaths are attributable to total emissions in a given year: roughly 200,000 for the former to roughly 103,000 to the latter.

This story was produced by The Atlantic’s CityLab as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

This story was produced by The Atlantic’s CityLab as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.