As global emissions continue to rise, the idea that the world will likely overshoot its climate targets is increasingly becoming a reality. In response, a growing contingent of companies have been looking to a technology known as “direct air capture,” or sucking carbon dioxide from the air, to help curb climate change. On Tuesday, this nascent industry got a boost when dozens of companies, nonprofits, foundations, and universities formed a coalition to organize the carbon removal industry and bring together people who have so far been thinking about and working on direct air capture in isolation.

Carbon removal technology is a growing but still controversial component of the global response to climate change. In April, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the United Nations’ top climate body, said that keeping global warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius will require removing some carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. And despite opposition from some environmental advocates, groups like the DAC Coalition believe direct air capture is one way to meet those climate goals.

The new group, known as the Direct Air Capture Coalition, is registered in the U.S. as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization but will have a “global focus,” according to Axios. Members include for-profit companies such as Climeworks, which opened the world’s largest carbon-capture facility in Iceland last year, along with “partners and observers” like the nonprofit World Resources Institute and New York University’s Energy, Climate Justice, and Sustainability Lab. The goal, according to the group’s website, is to bring together leaders from the technology, business, finance, government, and civil society sectors to “educate, engage, and mobilize” the world toward carbon removal.

“There is no single nonprofit organization that is focused on accelerating deployment and doing so in a way that is effective, that is sustainable and that is equitable,” Jason Hochman, the coalition’s co-founder and senior director, told the news site Protocol. “So we’re trying to change that.”

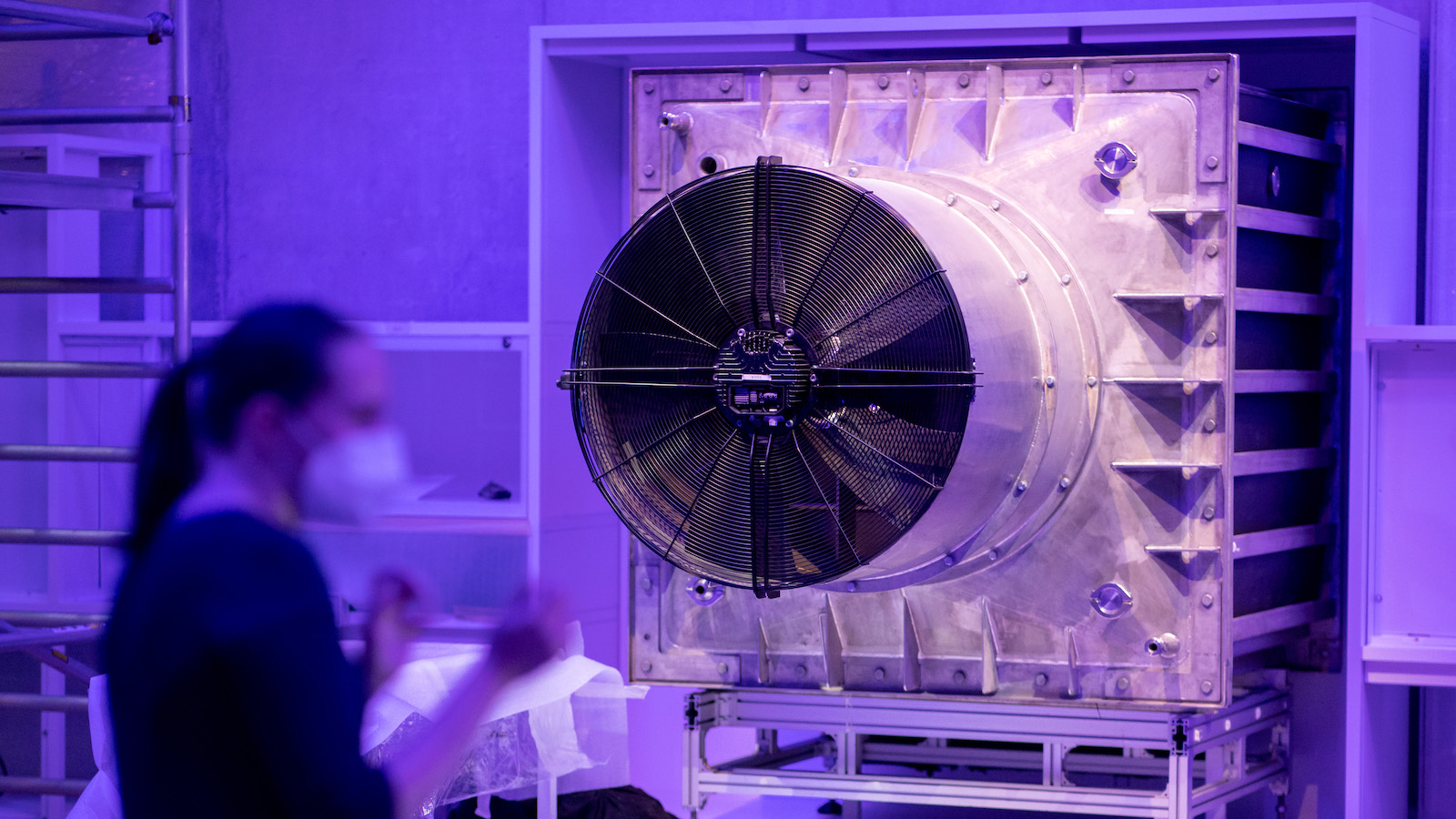

Carbon dioxide removal, or CDR, is a broad category that encompasses both natural solutions and technology. Ecosystem-based strategies include creating “carbon sinks” by planting trees or restoring wetlands that pull carbon from the air and sequester it in biomass, water, or soil. Technologies like DAC are another component, using large fans to suck in air and a chemical reaction to filter out the pure carbon dioxide, which would then be piped to underground storage areas around the country or turned into products like concrete.

Direct air capture technologies have not yet been tested on a large scale, and can be prohibitively expensive, costing several hundred dollars to remove a metric ton of carbon dioxide. But local governments in states like Colorado and Arizona have already begun to move forward with carbon removal. And the federal government has supported the idea, too; last week, the Department of Energy announced that it intends to fund a $3.5 billion carbon capture and storage program as part of last year’s bipartisan infrastructure law.

The initiative would create four regional DAC hubs that would each capture and store at least 1 million metric tons of carbon dioxide each year. But according to the department, “CDR will need to be deployed at the gigaton scale” by the middle of the century — capturing 1 billion metric tons of CO2 annually, approximately the amount produced by 250 million vehicles.

The Department of Energy promised that it would “emphasize environmental justice, community engagement, consent-based siting, equity and workforce development” in developing CDR projects, and said that this strategy would need to go hand-in-hand with decarbonizing the economy. But environmental justice groups like the Climate Justice Alliance criticized the decision to promote carbon removal technologies, arguing that funding should instead support “real and proven” renewable energy projects in areas that are most affected by pollution.

“The mere promise of DAC technologies acts as cover for continuing fossil fuel extraction and use, resulting in continued harm to frontline communities,” Basav Sen, the Climate Justice Project Director for the Institute for Policy Studies, said in a press release. “It is also a dangerous gamble, since we are already in the midst of a severe climate crisis, and the promise of DAC may never materialize and only harm frontline communities in new, unacceptable ways.”

Instead, the alliance has called on President Joe Biden to ban new oil and gas leasing on federal lands, stop approving fossil fuel projects, and declare a climate emergency under the National Emergencies Act, which would allow the government to fast-track renewable energy development.

Hochman told Protocol that the DAC Coalition wants to play a role in getting these regional hubs off the ground, although the organization won’t be engaging in direct lobbying. The group’s next steps include holding a summit in the fall, with the goal of developing a strategy to guide the industry through 2030.