Alexis MadrigalThe San Luis Reservoir in the center of California is a key link between the State Water Project and the federally funded Central Valley Project.

Hood, Calif., is a farming town of 200 souls, crammed up against a levee that protects it from the Sacramento River. The eastern approach from I-5 and the Sacramento suburb of Elk Grove is bucolic. Cows graze. An abandoned railroad track sits atop a narrow embankment. Cross it, and the town comes into view: a fire station, five streets, a tiny park. The last three utility poles on Hood-Franklin Road before it dead-ends into town bear American flags.

I’ve come here because this little patch of land is the key location in Gov. Jerry Brown’s proposed $25 billion plan to fix California’s troubled water transport system. Hood sits at the northern tip of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, a network of human-made islands and channels constructed on the ruins of the largest estuary from Patagonia to Alaska. Since the 1950s, the Delta has served as the great hydraulic tie between northern and southern California: a network of rivers, tributaries, and canals deliver runoff from the Sierra Mountain Range’s snowpack to massive pumps at the southern end of the Delta. From there, the water travels through aqueducts to the great farms of the San Joaquin Valley and to the massive coastal cities. The Delta, then, is not only a 700,000-acre place where people live and work, but some of the most important plumbing in the world. Without this crucial nexus point, the current level of agricultural production in the southern San Joaquin Valley could not be sustained, and many cities, including the three largest on the West Coast — Los Angeles, San Diego, and San Jose — would have to come up with radical new water-supply solutions.

I’ve come here because this little patch of land is the key location in Gov. Jerry Brown’s proposed $25 billion plan to fix California’s troubled water transport system. Hood sits at the northern tip of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, a network of human-made islands and channels constructed on the ruins of the largest estuary from Patagonia to Alaska. Since the 1950s, the Delta has served as the great hydraulic tie between northern and southern California: a network of rivers, tributaries, and canals deliver runoff from the Sierra Mountain Range’s snowpack to massive pumps at the southern end of the Delta. From there, the water travels through aqueducts to the great farms of the San Joaquin Valley and to the massive coastal cities. The Delta, then, is not only a 700,000-acre place where people live and work, but some of the most important plumbing in the world. Without this crucial nexus point, the current level of agricultural production in the southern San Joaquin Valley could not be sustained, and many cities, including the three largest on the West Coast — Los Angeles, San Diego, and San Jose — would have to come up with radical new water-supply solutions.

Too much is being asked of the Delta. The levees that define the region’s water channels are aging, and geologists and climate scientists worry that earthquakes or rising sea levels could rupture them. More immediately, the Delta ecosystem is collapsing. Native fish species are on the brink of extinction in part because of this massive water-transfer apparatus. The unnatural flows disrupt their natural habitat, and when they reach the pumps—which they often do, despite the state’s efforts—they die. The Delta smelt population, for instance, has gone from hundreds of thousands to tens of thousands in the last few decades.

Brown’s father, Pat, oversaw the completion of this productive, destructive system, and Jerry Brown himself tried to fix it during his first round as governor 30 years ago. A statewide vote thwarted him then, but he’s ready to try again. His proposal, the Bay Delta Conservation Plan, would bore two tunnels longer than the English-French Chunnel underneath the Delta, while simultaneously restoring thousands of acres of wetland.

The water intakes for the tunnels would flank Hood: two to the north, one to the south. Water that would have flowed down through the Delta, then sent south, will be diverted here instead. If the water goes underground at Hood, passing through new, high-tech fish screens, it will pick up fewer endangered creatures on the way to the south Delta pumps. State officials hope that means federal environmental agencies will stop interfering in their water delivery operations.

It is an audacious plan, one that seems to come from another era, where governments were more ambitious in their transformation of the natural world. Brown explicitly invoked this grand spirit in unveiling an early version of the plan in mid 2012.

“There’s a lot of history here. Taking this history, I can say that the proposal that we’re unveiling today is a big idea for a big state for an ambitious people that since the Gold Rush has been setting the trends and tone for the entire United States,” Brown said. “California has prospered because we’ve taken risks, we’ve pioneered, and we’ve been able to collaborate. Yes, there is going to be some opposition. Political, citizen, activist, whatever, it goes with the territory.”

Hood is one base for that opposition. Everywhere you look in this part of the state, you see signs that read, “Stop the Tunnels! Save the Delta!” The tunnels would take at least 10 years to build, and the $15 billion price tag, which doesn’t include $10 billion for habitat restoration, could go up, based on the experience of other underground projects like Boston’s Big Dig. Huge construction vehicles would patrol the roads for a decade. There would be regular detours along River Road, a main thoroughfare. And at the end of all that inconvenience, there would be three massive industrial facilities flanking the river, jutting into adjacent fields.

The locals don’t like that, but their real worry is that the tunnels will be used to drain the Delta’s fresh water — in effect, wiping out the farmers here in favor of bigger southern producers. At the moment, the Sierra water that flows through the region overground acts as a hydraulic barrier to keep salty San Francisco Bay water from creeping eastward. The tunnels will change that. The Delta, they fear, could end up wiped out like Owens Valley, once home to a 100 square mile lake, which Los Angeles drained like a cold beer on a hot day. Chinatown was made about that battle, and Delta residents don’t want to be immortalized in a sequel. Only this place wouldn’t become a dustbowl like Owens Valley so much as a saltwater world. As soon as the tunnels went into operation, much of the fresh Sierra runoff would leave the Delta waterways, and higher salinity Bay water would creep in. Then, perhaps, over time, once southern interests stopped relying on the Delta’s above-ground channels for water transport, the state might not be so eager to pay the hundreds of millions of dollars needed to keep the local levees standing. Sea levels are rising, and already, a few tracts of land have been permanently submerged.

Outside the Hood Market, the only open business in town, a man in a brown corduroy jacket and pants leans against one of the skinny white posts holding up the corrugated tin roof. I ask him if he knows Mario Moreno, the man I’d arranged to meet in town through the Hood community Facebook page.

“Is his truck here?” he asked, looking around at the four cars parked in the lot. “He’ll probably be here in that big SMUD truck.”

The town is boxed in by several large buildings, remnants of a time when the area shipped its produce by boat and rail. The man gazes blankly at them, finishing his cigarette and lighting another.

A Toyota Tacoma swings around the corner: In the driver’s seat, I recognize Moreno from his Facebook profile. Cropped black hair with some salt and pepper around the sides. A groomed mustache. Aftershave wafts out of the cab.

“Chetttyyy,” he says to the man in the corduroy.

“Mario!” comes the reply.

The three of us stand in the parking lot, and I bring up the tunnel project. The topic turns to Jerry Brown.

“Fuck him, man,” Nadar Chetty says.

“We’re like ground zero for this whole thing,” Moreno says. “Aside from the politics and the technologies and the engineering, which would be a big massive project and I don’t know—”

Chetty cuts in, “This town, a good 65 percent of the population is third, fourth, fifth generation.”

Moreno, who works for the local utility, is related to dozens of people in town. Most of them originally came up from the southwestern Mexican state of Mihoacan as part of the WWII-era bracero program, and then perched for a while in Colorado before heading west. Moreno’s mother arrived in Hood in 1945. She lives in a mobile home at the end of Fifth Street, which dead-ends into a farm. Across a vibrant green field sits the impressively restored Rancho Rosebud about a mile to the north, and right next to the likely location for one of the intakes. It was once the home of the most powerful man ever to live in Hood, William Johnston, a Pennsylvanian who became a state senator and two-time California delegate to the National Grange.

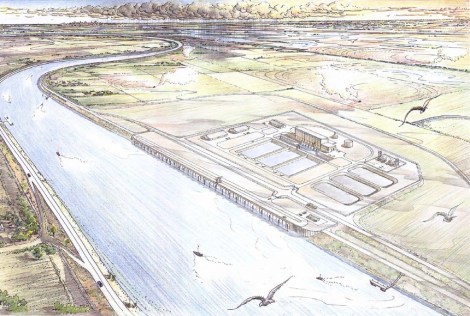

A concept drawing of a tunnel intake near Hood, as envisioned by the Bureau of Reclamation. The fish screens are located in the structure along the canal. If the plan goes through, there will be three similar intakes along the Sacramento River near Hood.

Picking up the theme, Moreno says, “Absolutely, lot of history here, lot of farming families.”

“History that would be destroyed by this,” Chetty declares. Areas around Hood will become the staging grounds for the biggest alteration of the ecological and economic landscape in the Delta since the 1960s, when the State Water Project began, or even the 1860s, when people like Johnston carved farmable Delta land out of the swamp.

“So those are the things I look at, how it’s gonna affect the people who are here,” says Moreno. “Take it away from all the politics. I do know that this is a state that needs water and manages water resources, but have we done everything that we can? It’s just like in energy efficiency, what I do. I make sure that we do everything that we can before we start bringing on new supply.”

Go to a faucet. Turn it on. This — water flowing out, clean, drinkable, always-on — this is the lifeblood of society.

A cup of water is eight ounces. There are 16 of those in a gallon. In the water world, the main unit of measurement is not the gallon, but the cubic foot of water. One cubic foot is 7.48 gallons, or 62.4 pounds of water. Imagine an office water cooler, but 1.5 times bigger.

If a little bit of water is moving, it’s quantified in gallons per minute. A bathroom sink might deliver 1.5 gallons per minute. If a lot of water is moving, then the measurement of choice is cfs, cubic feet per second. A fire hose delivers about 4.5 cubic feet per second.

If water is sitting in a reservoir or being bought or sold, then people talk about acre-feet of water. One acre-foot of water equals 43,560 cubic feet, or 325,851 gallons. An unofficial rule of California water politics holds that if you want to make an amount of water sound large, use gallons. If you’d like to make it sound small, set your units to acre-feet or even million acre-feet.

Compare: 1) Los Angeles uses about 600,000 acre feet of water per year. 2) Los Angeles uses 195,510,600,000 gallons of water per year.

For the rest of this article, I’ll go with acre-feet because it reflects the scale of these projects better. They are not working at your puny human level.

So, to set the scene: All of the golf courses, parks, and other “large landscapes” in the state use 700,000 acre-feet. That’s a bit more than Los Angeles uses.

But then take a look at Kern County, at the southern end of the San Joaquin Valley. Last year, it consumed 2.7 million acre-feet of water. The vast majority of it went to agriculture. Kern County’s water usage could support an urban population of 15.9 million people at L.A.’s per capita consumption rate.

Not to let the thirsty southern Californian cities off the hook, but agriculture soaks up the vast majority of water in the state. Depending on the year, up to 80 percent of the water diverted by people goes to farms and ranches. If you include water used for environmental purposes, like having flowing streams and places for aquatic animals to live, then agriculture’s share drops to 40 percent, with the environment getting roughly the same amount, and all urban uses gulping down the last 20 percent.

Alexis MadrigalThe cities of the southland depend, at least for now, on water imported from other places to the north and east.

This water doesn’t usually come from streams adjacent to family farms. Much of it is pumped from underground aquifers. And the rest is delivered by two vast interconnected hydraulic machines that push melted snow from dams in the Sierras, through the Delta, to massive pumps that fill the aqueducts traversing the state. One machine is called the Central Valley Project, and it’s managed by the federal government under the Bureau of Reclamation, the same agency that built the Hoover Dam. Historically, it’s sent 7 million acre feet of water south of the Delta.

The other machine is California’s own concoction. That’s the State Water Project, and it was cemented into place by Gov. Pat Brown. It’s never delivered less than 1.1 million acre feet of water to the south, and it’s often delivered millions of acre feet.

The Central Valley Project sends about 70 percent of its water to farms and 30 percent to cities. The State Water Project’s proportions are inverted: It delivers water to the southern California cities and a few, large farming districts. The two projects work in concert and share some facilities, including the vast San Luis Reservoir in central California, not to mention the byways of the Delta. Both machines are controlled at a Joint Operations Center in Sacramento, where an interactive map on the wall shows the condition of the waterworks as best as it can be known.

Taken together, this is the infrastructure that does the dirty work of California’s long-held water policy: Take water from the north and move it to the south.

It’s a kind of landscape arbitrage. In a sunny place, water tends to be the main constraint to growth. Add water and anything — people, alfalfa, nine-hole golf courses, swimming pools — can proliferate endlessly. According to the logic of half a century ago, when the word ecosystem was just coming into the common parlance, water in a wet place does humans no good. Water in a dry place? Well, that’s Los Angeles. That’s the fields of the San Joaquin Valley. That’s the Inland Empire.

A Department of Water Resources Annual Report, released in 1968 as the State Water Project neared completion, laid it out bluntly:

California is in the midst of constructing an unprecedented water project for one essential reason — the State had no alternative. Nature has not provided the right amount of water in the right places at the right times. Eighty percent of the people in California live in metropolitan areas from Sacramento to the Mexican border; however, 70 percent of the State’s water supply originates north of the latitude of San Francisco Bay.

And the construction was unprecedented. The State Water Project is the biggest of its kind in the country. The Banks Pumping Plant at the south end of the Delta can send 10,300 cubic feet of water 200 feet into the air and then down into the California Aqueduct. In a given year, the State Water Project can deliver a maximum of 4.1 million acre-feet of water, though it averages more like 3 million. The Central Valley Project delivers more than twice that volume down south through the Delta-Mendota Canal.

Moving so much H20 from north to south requires tremendous amounts of energy: The two projects alone consume nearly 5 percent of all the state’s electricity. The San Joaquin River, which naturally flows north and west, flows backward during irrigation season. Water released from the Oroville Dam in the Sierra mountains takes 10 days to travel the whole State Water Project, branching across to the Bay Area and Silicon Valley, then down the Central Valley and over the Tehachapi mountains, and then into a pipe along the edge of Los Angeles to the Inland Empire, where eventually, after everyone’s taken the water they’ve paid for, what’s left fills a small lake on the edge of what was once known as the Great American Desert.

For a long time, the system has worked. But the infrastructure is getting old, the political arrangements that underpinned it are breaking apart, and climate change is threatening droughts and sea-level rise — all of which terrifies powerful farmers and big-city water managers south of the Delta.

The state’s water system and the farms and cities it feeds are perceived to be so important to the functioning of the country that when a drought hits California, the White House pays attention. This month, President Obama visited the San Joaquin Valley. He explicitly connected the drought to climate change and the national interest. “California is our biggest economy. California is our biggest agricultural producer,” he said. “Whatever happens here happens to everybody.”

Alexis MadrigalBy the time water reaches Lake Perris — the southern end of the State Water Project, 90 miles east of Lost Angeles — it has traveled 700 miles from the Sierra Nevada Mountains.

In the desert of Riverside County, there is a slatted metal grate sunk into a hill sloping towards the human-made Lake Perris. A small door would allows a skinny maintenance man to shimmy down via a crude ladder bolted into the concrete tube.

There’s no plaque to indicate what this place is. There are prickly plants. A few morning walkers. A couple fishermen down on the imported sandy beach. Empty fairgrounds stand just on the other side of the dam.

It is just one more patch of California scrub desert down the road from a Jiffy Lube and a logistics center.

The only sign is the sound, a roar rising up and out from the grate. It sounds like a mountain stream transported into the middle of the desert and that is what it is. I’ve found the very end of the State Water Project’s aqueduct. The water rushing under my feet probably fell as snow up in the Sierra, 500 miles from here, then it melted, rushing down the Feather River to the 3.5 million acre-foot Oroville Reservoir, or into the Bear and Yuba, two other tributaries of the Sacramento River. The Sacramento, then, flows into the Delta — the connection between the mountains, the Pacific Ocean, and the watershed of the Central Valley.

As the water rushes to meet up with the San Joaquin River and its tributaries along its natural southeasterly path towards the San Francisco Bay, vast pumps divert the flow into a reservoir at the bottom of the Delta. There, they suck it in and shoot it 200 feet up into the California aqueduct, a deceptively narrow canal that runs 30 feet deep. Something like 75,000 gallons rush onward each second. This cold, blue ribbon runs down the western edge of the entire Central Valley, getting a boost from pumps when it falls too close to sea level as it winds among almond orchards, past prisons, around ratty vineyards, behind Jack in the Boxes, and through communities built to serve the needs of I-5 travelers, people who want to leave as quickly as possible.

This is the state’s own aqueduct. Like the federally run Central Valley Project’s Delta-Mendota Canal, it’s a product of the great age of Reclamation, a time when any river water reaching the ocean was considered a waste of potential.

This is the state’s own aqueduct. Like the federally run Central Valley Project’s Delta-Mendota Canal, it’s a product of the great age of Reclamation, a time when any river water reaching the ocean was considered a waste of potential.

The two water projects meet up near the San Luis Reservoir, a joint state-federal facility a couple miles east of I-5 and a smidge north of the latitude of Santa Cruz. Set amidst the fractal buckling of the hills, the thick wall of the dam that holds in the weight of the water is a spectacle of flatness. It is so flat and so large as to simulate the horizon, though it’s higher and smoother, straight as a pencil line drawn sharp and fast against a ruler.

In this drought year, which follows two other drought years, every single blade of grass that is not managed by humans is brown. Where the blue water splashes onto the soil, it erupts into oversaturated greens almost libidinous in their vibrancy. Where the water hasn’t touched for long enough, there is sand, and not even the husk or memory of plants. The highway does not pass over a single stream with running water for 250 miles. There are tumbleweeds caught in the rows of almond trees in Kern County.

At the bottom of the valley, the water runs into the Tehachapi Mountains. There, a few miles off the I-5 — past a natural gas outfit, a vineyard, and a sand and gravel purveyor — a building has been pounded into the mountainside, as if by Tolkien’s dwarves. These are the great Edmonston Pumps, which send 110 million gallons an hour up across the pass. They do their work silently, the wind whipping around them, cows grazing in the distance, the lights of the gas company’s facilities blinking in the dusk. These pumps are one of the many superlatives of the system: Nowhere in the world is water pumped higher than right here from the dwarf building inside the mountain.

Once on the other side, the water is fed into the vast distribution networks that the Metropolitan Water District uses to dispense water to local utilities across the southland. This service does not come cheap. Over the past 10 years, north-to-south water have doubled in price to $800 per acre foot, or about on-fortieth of a cent per gallon. This is considered very expensive in the world of Big Water.

After the L.A. basin, the water rolls on through a pipeline, pushing into the Inland Empire — a land of relentless sun that is, with the exception of Palm Springs, the end of civilization before the great western desert takes over with continental force and distance.

And here, we find another great flatness. A dam, surrounded by rocky outcroppings and nearby mountains, hulks awkwardly behind the Riverside Fairgrounds. This is the Lake Perris reservoir, the southernmost piece of the State Water Project, the end of the line. Early on a February morning, with the sun rising over its beaches, fishermen’s trucks pulled up to the water, poles leaning on their tailgates, pheasants running across the roads, and leafy trees swaying in a slight breeze, it could easily be called beautiful. For decades, various levels of government have touted the “recreation” benefits that reservoirs deliver. In the desert, just seeing water and the possibility of trees is a relief.

Alexis MadrigalWater pours silently and invisibly into the Lake Perris reservoir.

It’s hard to spot the place where the Sierra water enters this desert holding tank After driving back and forth along the lake’s western edge, I ran into a state park official exiting a port-a-potty. He chewed on his soul patch for a moment. No, he didn’t know, brah. But he led me back to the main office — a pre-fab building with a small porch and a large grill — and there, a man told me to drive back up the road and look for a small shed on the side of the road.

A couple minutes up the road, I saw the humble shed. The bricks that covered its exterior blended seamlessly into the surroundings. I pulled off the road into a convenient parking spot labeled 10 minute parking, as if someone had expected this spot to receive a crush of visitors.

And that’s when I saw the grate and I heard the water of the Sierra. In the blackness, an ellipse the precise azure of the sky shimmered.

The desert surrounded me. The sun rose higher.

When I asked one Riverside local if she’d ever gone to the lake, she wrinkled her nose and rolled her eyes. “Not really, it’s manmade,” she said.

Richard White, a Stanford historian of the American West, pointed out to me a funny paradox that crops up all over this state: “The least natural places in California become the only refuge of the natural world.”

When Gov. Pat Brown came into office in 1959, both northern and southern Californians needed something from the existing water system. The north wanted a dam to tame the Feather River, which had done severe damage in the winter of ’55-’56. The south needed the water that the dam would impound. To push the original State Water Project through, Brown needed to unite the flood control interests of the north with the water supply interests of the south — and thread the needle right through the Delta just south of the state house in Sacramento. His biographer Ethan Ratrick describes his chutzpah. “You’ve got to remember that I was absolutely determined that I was going to pass this California Water Project,” Brown declared years later. “I wanted this to be a monument to me.” And it has been for 50 years.

Library of CongressA miner blasts through rubble with a hydraulic cannon in an 1883 illustration from The Century magazine.

But there’s a basic tension inherent in California’s water story. Ever since the Gold Rush days, people in the state have claimed a right to the full flow of water flowing past their own land — so-called “riparian rights.” But what if the guy upstream wanted to use the water for, say, mining? He might impede the flow. This did, in fact, happen. And the miners coined the tagline “First-in-time, first-in-right.” If you could get to it, you could use it.

Eventually, the State Supreme Court ruled in 1886 that people who owned land along the rivers had first dibs on the flow of the water. This victory for riparian rights had consequences that have lasted for decades. “Millions of acres of arable land throughout the Central Valley could not qualify for riparian rights because they were not adjacent to reliable sources of surface water, and their water rights were now effectively subordinate to those of riparians,” wrote the Public Policy Institute, a California think tank, in a 2011 book on water management. “This meant that downstream riparians — including those farming the lower reaches of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers and in the Delta itself — could claim the full, unencumbered flow of the rivers despite the burdens such claims would place on upstream appropriators. Moreover, riparian rights would become an obstacle to developing water supplies for California’s growing cities, which sought to acquire supplemental water sources.”

A series of laws has tried to patch up the leaky system since then, the most important of which was the Water Commission Act of 1913, which serves as a milestone even today. Everyone who has wanted to appropriate water since 1914 has needed a permit. Those who claimed their rights before that time are considered “senior,” and they don’t need anybody’s stinking permit. Those are some valuable rights. A 1928 constitutional amendment knocked the riparians down a peg, saying they couldn’t claim the whole flow of a river, but rather only a “reasonable and beneficial” amount of water. Unfortunately, reasonable and beneficial are contestable terms. Basic question remain unresolved: Does one’s historical standing or land location mean anything? Or should all water flow to the highest-value uses?

This Chitty Chitty Bang Bang of a system kept on clanking along through the creation of Central Valley Project and the State Water Project and all the way up through the environmental legislation of the 1960s, when people began to ask, “Don’t the fish need water, too?” just as the cities and the San Joaquin Valley were exploding.

Banks Pumping Plant near Tracy, Calif., is not a solution to California’s water riddle, or a monument to the Brown family. It’s the biggest pump in the Delta: Turned all the way up, it’s like 2,300 fire hoses all blasting away at once. It’s also one of the pump systems that has drawn ferocious protests from environmentalists for chewing up fish, despite the state’s efforts to keep them out of the massive machines. The plant can exert such force on the Delta’s waters that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service now regulates how and when pumping can be done to protect endangered species.

Jim Odom, who runs the Banks Plant, is a humble guardian of the status quo. I visited him there on the day the Department of Water Resources announced that, for the first time ever,the State Water Project would not be delivering any water to the cities or farms that pay for its survival. Scientists and analysts determined that there just wasn’t enough snow in the Sierras or water in the reservoirs, the state explained, to keep the fisheries alive while sending water out of the Delta. Some water that their customers had banked would still move, but 0 percent of the water they’d be allocated in a good, wet year would be sent southward. In effect, Californians were told that more than a million fewer acre-feet of water for farmers and cities would be on the move.

Jim Odom, who runs the Banks Plant, is a humble guardian of the status quo. I visited him there on the day the Department of Water Resources announced that, for the first time ever,the State Water Project would not be delivering any water to the cities or farms that pay for its survival. Scientists and analysts determined that there just wasn’t enough snow in the Sierras or water in the reservoirs, the state explained, to keep the fisheries alive while sending water out of the Delta. Some water that their customers had banked would still move, but 0 percent of the water they’d be allocated in a good, wet year would be sent southward. In effect, Californians were told that more than a million fewer acre-feet of water for farmers and cities would be on the move.

We stood in the charmingly old-school tour reception room, underneath foam picture boards showing the construction of the State Water Project, and contemplated that for the first time ever, the enormous system wasn’t doing what it had been built to do.

“Nobody wants to shut off any water who works for the State Water Project. We want to deliver you water. That’s what we’re here to do,” Odom told me. “And it’s not like I don’t want to get up and do my job. I really like my job.”

This is not the most interesting job that Odom has had. He’s been a movie stuntman. He’s a champion flat track motorcycle racer, the king of Altamont Speedway (yes, that one) out when this area used to be the stomping grounds of the Hell’s Angels.

Odom is in the Motorcycle Hall of Fame. I found him in a 1971 advertisement for Suzuki sitting on a TM-400 Cyclone, with a trophy in one arm and a bikinied blonde woman in the other. Empty desert opens out behind them. The tagline reads, “Built to take on the country.”

In 2004, well into his middle age, Odom rode a motorcycle called the Ack-Attack more than 300 miles an hour over the Bonneville Salt Flats. As he neared the end of his ride, in the spot where his speed would be measured for world-record purposes, a crosswind kicked up and the conditions on the track deteriorated. A writer on the scene says Odom slammed on the throttle and tried to “muscle his way through the wind and soft, slippery, rutted salt.” It didn’t work. His front wheel left the ground. The bike started to roll, its canopy popping off. His emergency parachute stopped the roll, and he got out of the Ack-Attack unharmed.

Now, at the State Water Project, he controls the throttle of a far more powerful machine.

Alexis MadrigalThe channel leading from the Clifton Court Forebay into the Banks Pumping Plant can send more than 10,000 cubic feet of water per second flowing into the California Aqueduct.

Nominally, his work is mechanical, but most of what increases or decreases his plant’s pumping has nothing to do with horsepower. As a whole, the State Water Project tries to generate electricity when energy prices are high and draw power to pump when prices are low. That makes keeping the pumping plants going that much more difficult. Plus, federal court orders relating to the Endangered Species Act can call pumping completely to a halt.

“Way above us, they’re mitigating and doing all the regulatory things and try to comply and do what we can do. But nobody thought about that. This was a feat in itself when we made it happen,” Odom said. “It was supposed to last for 50 years, and it has lasted for 50 years.”

Orders come down from the Sacramento Project Operations Center, where engineers and forecasters stare at a huge map and all kinds of models to try to figure out where and how much water to release and pump and store — based on variables like reservoir levels, the Sierra snowpack, and long-range weather models. Nothing’s instantaneous in a water grid: Remember, it takes 10 days for water released from Oroville Dam in the Sierra foothills to reach Lake Perris in Riverside County, and all along the way, people are pulling water out. There are dozens of reservoirs, dozens of contractors who wholesale the water, and dozens of legal agreements that govern what can be done.

The last several decades have seen failed attempt after failed attempt to find some kind of a balance that protects the environment, farmers, and the people with the most money to pay for water, who turn out to be living in the cities.

The tunnels won’t solve all of Odom’s problems down here at Banks. (The only opinion he offers on the project as a whole is that “there are some pros and cons.”) But they would give him and the rest of the Department of Water Resources operators more flexibility in how they run the system. They could have a more consistent water supply that was cleaner and contained far fewer fish, thanks to the fancy new screens on the intakes near Hood.

We drive up on top of the pumps. Massive gates can open and close to let water in and out. They’re paired with another set on the other end of the canal, at Clifton Court Forebay, the giant holding tank for the water that enters the system. The current plan would bring two kinds of water into the Forebay: water from the tunnels and water that sloshes in overland through the Delta. The tunnel water would, in theory, have no fish and less organic material, which would reduce costs for people treating the “raw” water.

In the hills behind us, old wind turbines, installed with tax credits dreamt up by Jerry Brown in his first turn as governor, have mostly stopped spinning. The hills are brown for miles around. The squat pump house doesn’t look like anything special, certainly not a force disrupting the whole Delta ecosystem. Odom points out where the tunnels would terminate, pouring fresh water into the reservoir that feeds the pumps. He says to look for a small grove of eucalyptus trees.

State Water Project facilities like Banks were not designed with the needs of fish hatchlings in mind. The project’s goal, explicitly, was to dominate nature, not nurture it. Now that the ecological problems are so large that they can’t be ignored, the state has extended — not changed — its logic. To the squishy challenges of working with biology, it responds with the world’s largest tunnel boring machines. The goal remains: Deliver as much water south as possible.

The original State Water Project contained a crucial omission: It did not codify how the water would be split up between the north and the south, leaving that crucial detail up for future squabbling, which, essentially, has never ended.

My Hood tour guide Mario Moreno introduces me to Brian Whitney, a bear of a man in coveralls who wears a resolute white fu manchu mustache. Whitney’s grandfather bought the land he farms in 1945. His father, Galen Whitney, fought the original State Water Project plan. When the bond measure passed by a thin margin, Brown wrote in his diary, “Water wins.” Galen Whitney lost.

Later, in the 1980s, Galen Whitney battled Jerry Brown’s effort to complete his father’s vision with a so-called “peripheral canal,” which would have sent water around the Delta, knocking out 6,600 acres of agricultural land along the way. “When I was a little kid, the peripheral canal was gonna come through,” Brian Whitney tells me. “It was gonna be one big ditch right along that levee all the way back. And my dad has been pushing — well, he’s passed away now, but for his whole life he was pushing against that.”

That time, Whitney and his allies won. And that battle set up the way a lot of people around the area think about the tunnels. If they won once, they can win again, they figure.

Newer people in town are rushing off to meetings to listen to the authorities. But Whitney isn’t hearing any of it. “Him, he heard so many stories. He died pretty early. But man, I could tell he just got sick and tired of holding it back, trying to push them back, just keep pushing them back. You look up Galen Whitney in this stuff. He’s been gone for 10 years, but man there’s a lot of people knew him. A lot of people didn’t like him. He did what he thought was necessary for his area. He kept pushing and shoving and kicking and scratching.”

Of course, everyone learned from the failure of the peripheral canal. Backers of the Bay Delta Conservation plan have tried to distance it from the old peripheral canal model. They distribute a whole pamphlet showing how different the tunnels are from the old canal. The new plan has less than half the water capacity, which means it will divert much less water from the area. Its above-ground footprint is much smaller. There are more fish protections. And a half-dozen other arrangements are probably better for the Delta than they were in the proposal that failed 30 years ago. But the Delta political forces refuse to see it as anything but an inglorious return of the peripheral canal.

What, I ask Whitney, do you want the state to do in the Delta?

“Leave it alone. It works just fine. Let them do a little cleaning, a little maintenance, on the levees,” he said. “It’s been working fine for 150 years.”

Working fine since this land was created in the middle of the 19th century. The process began in 1850, when Congress passed the Swamp Lands Act — a piece of legislation that made federal “swamp and overflowed” land available for sale to private citizens.

Meanwhile, up in the Sierras, where the water came from, miners were mowing down mountains with hydraulic cannons, then snatching the gold out of the rubble, and letting the rest pass downstream. The sediment piled up in the rivers, making them shallower, and more prone to flooding. This area has a complicated history, and it has always been about water and money.

The year Congress passed the Swamp Lands Act, William Johnston carved out his Rancho Rosebud, across the field from Moreno’s mother’s house, in 1850. As he and other Delta residents were building levees and beginning to reclaim the great backswamp, floods caused by the mining sediment swept through time and again.

Library of CongressChinese laborers in California, circa 1880.

Then, through crooked legislative dealings, most of the swampland in the state ended up being sold to just 200 wealthy people. They used Chinese immigrant labor to make a fortune building up the Delta as we know it today. “I do not think we could get the white men to do the work,” declared George Roberts, the biggest property owner in the Delta. “It is a class of work that white men do not like.” Rural Chinatowns cropped up in towns all over the region. The workers toiling in this New World delta sent money to the Pearl River Delta back home and tried to get by. With all that cheap labor, the farms in this part of California began to resemble the plantations of the South. When a newspaperman visited Rancho Rosebud, he found that Johnston had “so many cows, he is able to make butter all the year round.”

Not bad for a guy who arrived with a horse and a dog on at the edge of a seasonal inland sea so wild and difficult that the Spaniards had declined to build a mission there. For thousands of years before European colonization, in the winter, one would have stood in a vast, flooded field of reeds that stretched for miles, a home to migratory birds, elk, and grizzly bears.

But in the span of one man’s life, the Delta became 57 islands and tracts, crisscrossed by plumbing masquerading as river, barricaded in by 1,100 miles of levees. The land and water became levers in a money-making machine that dispensed most of its profits into the hands of a few lucky white men. In that, the Delta is a lot like Los Angeles, and not a bit more natural.

Yet a nostalgic narrative continues to animate the debate about the Delta. It focuses on returning the Delta to its rightful agrarian condition, the one that existed before the State Water Project and the decline of the fisheries and the constant threat of bad water. The idea that this was the natural state of things — the way the area once was, or the way it should be — is a powerful political fiction now butting up against physical and economic realities.

Many of the islands are sinking. The sea level is rising, creeping up the Delta. The levees are holding the water for now, but suburbs are approaching from all angles. Even if the tunnels never materialize, human development will continue to transform the region, just as they did back in Johnston’s day. Towns that feel rural are now a 15-minute drive from tanning salons and Subway sandwiches.

It is, by all accounts, an ominous time for the Delta and California’s water system. There are bad outcomes in all directions.

The most acute problem is the drought. “It’s bad. It’s dismal,” Carl Torgersen, deputy director of the State Water Project, told me before the big rains of the last few weeks. “The way things are right now,” he said, “it is the worst ever, at least since we’ve been keeping records.”

Even with recent rains, California’s on its way to another arid year, right after two other drought years. In the language of the United States Drought Monitor, 99 percent of California is “abnormally dry.” Ninety-five percent is in some kind of drought. Sixty percent is experiencing “extreme” drought conditions. And 10 percent is in the midst of an “exceptional drought.” Then-and-now satellite photos of the Sierras have circulated on the Internet because they vividly depict the scale of the problem. The west is missing its snowpack, which has long served as the ecosystem’s natural water storage for the dry summer months.

Water people have begun whispering the years of other bad droughts, almost like incantations. ’91-’92. That one was bad. ’76-’77. Oh. That one was terrible. Average precipitation is 50 inches for California; that year it was 17. And, Lord, ’23-’24, you don’t even want to know. There was so little river flow that the San Francisco Bay swept far, far into the Delta. During the dry season, sugar refiners at the C&H factory at the mouth of the Bay, in Crockett, Calif., had to send their barges 40 miles inland looking for fresh water. Eventually, they gave up, and started sucking in fresh water from across the Bay in Marin.

These recollections are soothing because the specter of climate change hangs over California. Could this unseasonably warm, dry weather be a casual occasion for a February picnic? Or is it an omen of doom? Will melting ice sheets lead to sea-level rise that drives salty Bay water deep into the Delta?

Climate models have a hard enough time peering into the long future — and now we want them to provide us with the kind of fine-grained analysis that would let a decision-maker in Riverside, Calif., know how to invest water infrastructure dollars?

But if drought is not your preferred apocalyptic scenario, there is always the flood. The ur-text here, which has spawned many different variations, comes from the Department of Water Resource–commissioned Delta Seismic Risk Report, prepared by two consulting companies in 2005. The more comprehensive Delta Risk Management Strategy report from 2009 found that “a seismic event is the single greatest risk to levee integrity in the Delta Region. If a major earthquake occurs, levees would fail and as many as 20 islands could be flooded simultaneously. This would result in economic costs and impacts of $15 billion or more.”

More recent investigations by the U.S. Geological Survey of individual points in the Delta have found that earthquake risks are higher than this report indicated. The reclaimed Delta islands are not less prone to earthquake damage than other types of land, as some Delta residents have contended, but actually will shake more.

People sometimes call this scenario “California’s Katrina,” because that is the most recent time in American memory when levees failed. It’s a terrifying prospect because the saltwater pulled in from earthquake-triggered floods could ruin the export water supply for months or even years.

But for people in the Delta, this scenario is unimaginable. Not a single resident has been alive for a major earthquake in the region. The fault lines nearby seem as mythical as devils or elves.

Water policy people have even named this tendency towards amnesia: “flood memory half-life.” The last major levee failure was in 2004, when the Jones tract in the southern Delta flooded in a “sunny day” event. It cost $50 million to patch things up. But that was 10 years ago. And in the intervening time, the levees have held. Each year that passes, the image of that blue water flooding onto the island fades.

The truth is that in any given year, the chance of a major, levee-destroying earthquake is very low. The chance that such an earthquake would occur in the dry time of a dry year, which is how a major water export disruption would occur, is even lower. “Multiple island failures caused by high water would likely be less severe than failures from a major earthquake,” the Delta Risk Management report maintained, “but could still be extensive and could cause approximately $8 billion or more in economic costs and impacts.” But it’s hard to take the proclamations of the risk planners seriously that, if they continue with business-as-usual, the Delta should expect 140 levee failures in the next 100 years, when the frequency of levee failures has gone down in recent decades.

And besides: 100 years? Most people in the Delta are looking ahead 100 days. Financial precarity is a perpetual crisis in places like Hood. And the state wants them to pay for more flood insurance and back a $15 billion plan to build tunnels? This is not wealthy coastal California; the per-capita income of Hood is $18,455. Sea-level rise and once-a-century earthquake risks can wait. There’s food to be put on the table.

Moreno has to think all the way back to’72 to recall a major flood, the one that hit Isleton, a Delta town south of Hood. The water came in the night. Two sheriff deputies noticed the lights were out at the Spindrift Marina, and when they arrived, they found not a road, but a river. Shortly thereafter, the water broke through another spot in the levee and the flood was on. A hundred forty thousand acre-feet of water were deposited on land, covering some areas 17 feet deep. A Heinz Pickle Cannery sustained serious damage. A reporter touring the scene a year later noticed “a surprising absence” of “pets and wild creatures.” They’d drowned. For years afterward, when folks from Hood headed down to Isleton for a football game or to visit cousins, the whole place smelled like pickles.

“You can find sympathetic people out there in the Delta but the fact is that they don’t stand for anything,” Richard White, the historian, tells me. “They are an uncountable minority in California. The census doesn’t even count ‘farmer’ anymore.” I mention the spate of recent stories in the Sacramento Bee that begin with anecdotes about a Delta farmer. White scoffs. “What the Bee does is that you have a farmer who comes in and stands in for farmers without ever asking how many there are. Or what this way of life is about.”

White is a bit of a curmudgeon. After a lecture at Stanford, I once saw him needle David Kennedy, a Pulitzer Prize–winning American historian in front of the whole crowd. Kennedy had been the lecturer.

But it’s worth asking: What’s the scale of the agrarian economy in the Delta? There are 7,000 farm jobs in Sacramento County, 8,000 more between Yolo and Solano county to the west. Add in San Joaquin County to the southeast (much of which is outside the Delta proper) and you’re looking at something like 26,000 farm jobs throughout the Delta region. If the state’s total agricultural commodity production is $45 billion, or less than a percent of California’s economy, then Delta agriculture’s contribution to the gross state product is a fraction of a percent.

The logic of this rough utilitarianism says that if the water can do greater good for more people elsewhere, then it should be used that way. The people in the Delta aren’t stupid. They know the richer areas of the states have more political pull.

“It’s the big corporate farmers like Del Monte and them. Those are the morons behind all this,” NadarChetty tells me, from his chair behind the counter of his general store. “As far as my business is concerned, my business will probably quadruple. I will be the biggest beneficiary of this tunnel. But at what cost? You cannot destroy a whole town and be the only beneficiary in town.”

His wife sits beside him, eating a plate of rice as he rails on.

“If they do what they say they’re going to do, we’re going to have salt water in this river during high tide,” he says. “If we’re going to have salt water during the high tide, then all these farmers right here are out of farming.”

“They are trying to help those farmers there, but what about the farmers here?” his wife asks.

“They are little people,” Chetty answers. “They are mom and pop farmers. They are not corporate.”

“Ohhhh, OK, so that’s what it is it,” she answers in mock surprise.

“They don’t give money to Jerry Brown for his reelection.”

“Ohhhh, so that’s what it is.”

“Or Darrell Steinberg.” Steinberg is the president of the California State Senate.

“Ohhhh. They are not as big as they are.”

“It should be Daryl Scumbag instead of Steinberg.”

Then they both go quiet and the fork scrapes again.

“The governor is like the father of the state,” Cheddy said. “How can you favor one child over the other children?”

Kern County, one of the state’s most water-hungry counties, has 60,000 farm jobs, according to California’s Employment Development Department. Many of them come tending tens of thousands of acres of almond orchards. California almonds have become one of its hottest exports: four of every five almonds sold in the world come from here, for gross revenues of $6.2 billion in 2012. To the north, in Fresno county, the Westlands Water District irrigates another vast set of trees, supporting some of the 40,000+ farm jobs in those areas. The Westlands almonds alone, as East Bay Express‘s Joaquin Palomino pointed out, require about 300,000 acre feet of water a year. That’s half a Los Angeles worth of the state’s precious water going to a single small region for a crop that is not exactly a dietary staple. This is optional — though profitable — water expenditure.

imakeamericaSpringtime in a Central California almond orchard.

The razor-sharp anonymous water blogger, On the Public Record, who revealed her identity to me and said she is someone working deep within the state’s water system, said almonds preoccupy her.

“Why are we supplying the world’s almonds? Why? Is that a choice we want to make?” she told me. “If there weren’t almonds for my existence, I’d be a little bummed. But I also feel like the Almond Board created demand for almonds. And now our almonds have to meet this glut. And now it’s a cycle. I come back to almonds all the time.”

For people around the Delta, the choice seems that stark: It’s the almonds versus us. That’s because pumping lots of water to the orchards through the tunnels will make Delta water worse.

The state says that no more water will be pumped out of the Delta than before, and that the tunnels are simply an alternative means of moving it. But the loss of the flow through the Delta will erode the hydraulic barrier that’s protected the farmers from the salty Bay water. And the intuitive economics of a very expensive project are simple: If it costs a lot, it will be used a lot. With all the debt the water importers would have to take on to pay for the tunnels, they’ll have to get plenty of water out of the deal.

“They aren’t building $15 billion tunnels for the fish,” economist Jeffrey Michael of the University of Pacific told me. “They need water to pay that debt.”

Michael is not chanting “Save the Delta” here. He is, rather, calling the state’s bluff. Publicly, state water representatives have talked a lot about the possibility of a catastrophic earthquake that would flood 20 islands, kills dozens of people, and foul up southern California’s water supply. They say they need to build the tunnels to guard the water supply against such a possibility.

“If the state really thinks that the probability of that event is as high as they say when they’re talking about tunnels, then the state has an economic and more responsibility to get in there and do what needs to be done to the levee system to improve it,” he maintains.

In the worst-case Delta earthquake scenario presented by the state, 600 people would die and there would be $500 billion in damage. “But only 20 percent of that economic loss was due to reduced water exports or a loss of the water pumping system,” Michael noted. The real costs would be to the infrastructure of the Delta itself, not to mention its property owners, and the state isn’t unveiling any big plan to guard against those damages.

In fact, by strengthening the levees, instead of building the tunnels, the state could get more flood protection for the water supply. The levee system is actually improving, thanks to smart investments by the state over the last 25 years. And for only a few billion dollars more, Michael maintains, the state could seismically upgrade the Delta’s levees, securing the water supply and the people who live behind them.

Alexis MadrigalSherman Island used to be dotted with bright green farms, but in 1987 the Department of Water Resources let salt water creep into its water supply.

Then, the state could pour the rest of the proposed tunnel outlay, more than $10 billion, “into local and alternative water supplies” — a bunch of different water fixes in a bunch of different places. That would make local communities more self-reliant and help solve the Delta’s environmental problems, because the pumps wouldn’t need to pull so much water out of the Delta.

A grid of small solutions is exactly what UCLA’s Mark Gold, director of the school’s Coastal Center, thinks could get Los Angeles to zero imported water by 2050. He rattles off actions could be taken in the near future: Invest in technological breakthoughs and infrastructure operations research. Change the laws that restrict the use of treated wastewater. Capture more stormwater. Desalt groundwater.

Take the Inland Empire Utilities Agency, which services the cities east of Los Angeles, and has been a model of water management in an arid place. It’s cut demand even as the population it serves grows. It’s gone in big on “recycled” water, which is collected and treated wastewater. And, along with several other water agencies, it has invested in desalting brackish groundwater from the Chino Basin. The utility’s total water production is about 200,000 acre-feet. It gets roughly 110,000 acre feet of that from groundwater, 25,000 acre-feet from local surface water, 35,000 acre-feet of recycled water, and 25,000 acre-feet of desalinated ground water. The remainder, then, a small slice of its supply, comes down from the Delta and through the Metropolitan Water District, which farms out the water to southern California districts.

“I’m not saying shut off the State Water Project,” Gold said. “But southern California’s and Los Angeles’s reliance on it isn’t necessary.”

After all, the vast majority of water production in California is already local, pointed out Martha Davis, executive manager for policy development at Inland Empire Utility. By her calculations, only 8 percent of the water used in the state actually flows through the Delta. “Groundwater is the backbone of California’s water system,” she said.

That’s not to say the Delta water isn’t important. It tends to have very low salinity, which allows local water districts to create significantly less salty water blends with a relatively small supplement of that Sierra supply. But nearly every water expert I spoke with outside the state’s Department of Water Resources had a long list of partial fixes to the dilemmas posed by California’s water system that would reduce the south’s dependence on that northern water.

“We’re never going to shut down the State Water Project,” the Pacific Institute’s Peter Gleick told me, echoing Gold. “We’ll supplement it with more local sources of supply. More treated wastewater. Desalination if we’re willing to pay the cost. Conservation and efficiency that cuts the demand.”

The Natural Resources Defense Council has been one of the tunnel plan’s biggest and most constructive critics. It has a comprehensive alternative plan for the Delta. The NRDC plan would reduce the two tunnels to one, and the overall flow through that tunnel would be 3,000 cfs, or one third of the current design. The council says that would cost $8.5 billion, which leaves a bunch of leftover money for other things. A few billion of it could go toward local water supply and conservation, the kinds of things Inland Empire is doing: recycling water, desalting groundwater, more efficiency measures. All of that would allow the state to decrease exports from the Delta by about half a million acre-feet. Flows would be higher in the Delta and there would be more water overall, if the NRDC’s numbers can be believed.

What’s more, the NRDC “portfolio” alternative would spend a billion dollars of the savings from a smaller tunnel to improve the levees in the Delta. As University of the Pacific’s Michaels said, perhaps the strangest thing about the pro-tunnel messaging is that the tunnels would do precisely nothing to protect the residents of the Delta from a horrible flood. It’s hard to understand how the state can talk up the danger to the water supply a 20-island flood poses while simultaneously ignoring what such a flood would do to the people living behind the levees.

One could certainly be forgiven for thinking the whole water supply system was about to collapse. That’s what the messaging looks like from action groups like the Southern California Water Committee, which is sponsored by the two biggest users of water from the Delta — Kern County and the Metropolitan Water District — and bolstered by a host of consultants and lawyers who stand to make a bundle on the huge tunnel project.

But even the Southern California Water Committee’s documents show how much progress has been made in the state’s water picture almost because of the gridlock in the Delta. The municipalities that take water from the Metropolitan Water District have transformed their strategies from heavy reliance on the State Water Project to far more local supplies, more storage, and more conservation.

Even with the worst conceivable climate change, the kind of global warming that brings 70-year droughts to California, the state might do OK. That seems counterintuitive, but that’s what Jay Lund, who heads the UC Davis Center for Watershed Sciences, loves about his model of the state water system, CALVIN. He and his colleagues ran a range of climate scenarios through CALVIN, asking for a look at what very dry, very warm scenarios might do to the state’s water system out to the year 2100. The results were shocking.

Basically, in CALVIN’s rendering of the future, the state’s economy is fine. “It was amazing how little the damage was to the state’s economy,” Lund said. That’s because the state’s cities sail through. First, they can afford to pay for water at quite high prices, so the economic gravity built into the model sends it their way. But it’s not just buying water from agricultural interests or through the State Water Project that saves them: A whole portfolio of nascent water ideas bloom.

Agriculture does not fare quite as well, but the state’s agricultural production only falls 6 percent. That’s despite increasing urbanization of agricultural land and, in the driest scenario, a 40 percent reduction in water deliveries to the Central Valley. “The farmers are all smart people and they’ll cut back the least profitable stuff,” Lund said. They’ll also fallow land, according to CALVIN — roughly 15 percent of the irrigated parcels currently farmed today, or 1.35 million acres. That sounds like a lot, but it’s only about 16,000 acres a year, from now until the end of the century. And, besides, the state’s farms and ranches generate $45 billion a year, but the state’s gross state product is $1.9 trillion. Viewed through CALVIN’s eyes, Big Ag means very little.

Throughout his description of these scenarios, Lund is almost cheery. He seems to enjoy cutting against the foreboding of the times. “We think climate change and think. ‘Oh this is terrible, and the optimization model says, ‘What’s the best I can make of this?’” The whole thing will work out, he says, because “the water system is run by all these smart people” who are, in fact, trying to get the most out of the water here. The current institutions and infrastructure are going to buckle one way or the other, and that will get people to reset their expectations of what water can do for California, which is still a whole hell of a lot.

When you look at what’s happening on a local level, California’s intractable water problem turns out to be Riverside’s solvable water problem and Fresno’s solvable water problem and Oakland’s solvable water problem. There’s a structure to the individual changes going on beneath the roiling chaos of the surface. And the political impasse has opened up space for people to come up with smart ways of making the system a little better and a little smarter.

What all this means for the tunnel plan is clear: If there are small-scale alternatives that reduce the risk of systemic collapse and strengthen urban self-reliance, then why spend $15 billion on two risky tunnels?

Lund doesn’t expect a grand bargain. “It’s hard to ask us to value things explicitly,” he told me. Everything has to at least seem like a win-win for everybody. Who wants to look farmers in the face and tell them that it’s their land that should be fallowed? Or tell the farmworkers who labor for that farmer that it’s their jobs that are going to go? Or tell the urban poor that their water bills are going to go up? Or tell the McMansion developers that there’s no water for their projects? (Actually, there may be a few volunteers for that last job.)

“It’s most likely we’ll just let things fail,” Lund said. “And if something fails that we really value, then we’ll go back and try to fix it.”

I take the road east out of Hood towards Elk Grove, a suburb of Sacramento with a population just under 156,000. In the mid-60s, when the State Water Project was under construction, Elk Grove was a town of 3,500, not much larger than the nearby Delta towns. Even in 2003, it was home to just tens of thousands. Then, between July 2004 and July 2005, Elk Grove became the fastest-growing city in the country. New construction jumped the 99 freeway like a wildfire: The farms just northeast of Hood got swallowed up and turned into the sorts of vast housing developments that remind one of China. In early 2000s satellite imagery, the once-green fields are dirt brown, inscribed with strange arcs that will one day be roads named Blossom Ranch Drive and Denali Circle and Novara Way and Fire Poppy Drive. Then the homes filled in, emptied through a horrific round of foreclosures, and refilled with new owners over the last few years.

We now know this kind of McMansion building was powered by vast financial machinery — a frenzy of loose money at low rates. Elk Grove is an echo of the boom. But it is also a glimpse of a new future that will end the Delta way of life. This place is engineered to be difficult for the upwardly mobile of the Delta to resist. It’s where Moreno himself lives, though he contemplates returning to Hood.

Elk Grove has learned from its ancestors’ mistakes. It’s not a post-war burb or 1980s gridded ranch development. The local Walmart is called a “neighborhood market” and the sidewalks that line its endless parkways are curved and xeriscaped, making the place feel walkable. Medium-density and single-family housing sit cheek-by-jowl with specialized healthcare centers and places that sell sushi wrapped into a burrito.

There is racial and ethnic diversity. At a school bus stop at the edge of a subdivision, a swarm of fathers waited to walk their children home. It’s not a retrograde place. In fact, it’s why people tend to come to America. What it lacks in charm it makes up for in orderliness and normalcy. Elk Grove is an everywhere.

But there is something about its whole-cloth conformity that might make a child long to see something authentic and wild. Inspired by a few too many novels, he might dream of collecting sticks along one of the creeks that divide subdivisions and weaving them into a raft. He’d stuff his backpack with a thermos and extra fruit rollups and ply his way down Franklin Creek. With a few quick scampers across a roadway or two, he might end up in the slough running past Mound Farm, where the first fields were planted in the vicinity of Hood, and if he kept traveling, he could go to Isleton, where the great pickle flood happened, and then to Rio Vista, where locals helped rescue a young whale who’d accidentally voyaged upriver. The boy would go sailing under the butter-yellow bridges, and past Locke, the home of the last rural Chinatown in America. Finally, he’d come out at Sherman Island, the western edge of the Delta, so close to the Bay he could smell it.

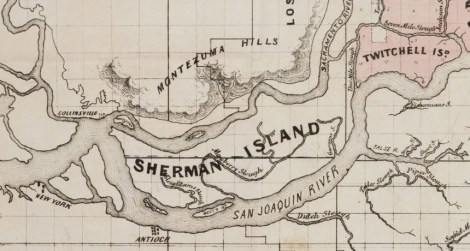

A historical map of Sherman Island, the first drained-and-leveed island created in the massive estuary where the rivers of California’s Central Valley meet the waters of the San Francisco River.

Most of that tract is owned by the Department of Water Resources. The island used to be filled with bright green farms like the rest of the Delta. But in the drought of 1987, the Department of Water Resources didn’t have enough water to flush down the Delta. The Bay’s salty tentacles crept into the freshwater supply, and the Sherman Island farmers sued the state a few years later. They got a few million dollars, and then the DWR bought them out. The land is still farmed, but it looks nothing like the rich orchards and asparagus fields further north. To be blunt: Sherman Island met the fate that local farmers fear up and down the Delta.

If an island was going to go, Sherman makes a poetic kind of sense. It was the first Delta land reclaimed by George Roberts, the Delta’s biggest 19th century property owner, through the Tide Land Reclamation Company after the passage of the Swamp Lands Act. Building it up was a wildly profitable business, especially with the help of the poor, stranded, desperate Chinese workers. “Reclamation” is a euphemism. The labor conditions were brutal. I ask White, the historian, what it might have been like to be in the Delta when humans began to intervene. “You’d be looking at a bunch tule reeds, you’d be bitten by mosquitoes, and you’d have malaria,” he said.

After the levees were built and the swampland was drained, the tule reeds were chopped down and roots plowed up, and the peat-heavy soil itself was burned. That began the process of what’s called “subsidence,” but you can think of as sinking. After the peat was exposed, it began to oxidize. Some people colorfully describe it as a slow-motion burning. The interior elevation of the island is now 20 feet below sea level.

Over time, the original peat-brick levees dried out and cracked. So the island flooded in 1861, 1871, 1874, 1876, 1878, 1880, 1894, 1904, 1906, and 1909. The sand and gravel that still form the levees were dredged-up leftovers from the hydraulic gold mining of the 19th century. In California, everything comes back to gold.

Now, you can stand on a levee made from sediment blasted from the Sierras, on the pivot between the estuary and the Bay, and watch a regiment of wind turbines spin happily away across the water. The industrial facilities of Pittsburgh and Bay Point steam in the distance. Down on the island floor, huge powerlines loom over cows. A few hardy people live in an RV park. Big succulent gardens poke through their fences. Fishermen sit on tailgates waiting for a bite.

If this is the slow apocalypse the residents of the Delta fear, it’s actually not so bad, just post-industrial. It’s a place where humans scavenge what they can from the land, after their efforts at improvement have failed. Land is not what it used to be, anyway. It’s not a proxy for money, which can now be created out of thin air, or derived from code. The economy has been dematerialized, based on intellectual property instead of physical things. A place like the Delta — and all farmland — is less important than it used to be, when enchanting food out of the soil was the purpose of life. That’s why economists don’t mind if most of the farmland goes away. We can always import food from some poorer place.

But for now, California’s water story is all about tradeoffs, and the writer behind the On the Public Record blog would like the public to be more aware of them. “I wish we made explicit societal choices. Say, ‘Yes, I would rather we supplied pistachios to the world than had a San Joaquin River’ or ‘No, I don’t actually want my lawn as much as I want to know there are salmon in our rivers.’ We can manage our water system to do a very large range of things, but we can’t do them all well,” she emailed me. “I wish we were guided by actual explicit choices, rather than by every water district manager trying to keep our status quo going just a little longer. If we knew we (all 39 million of us, overall) didn’t want to use water to grow alfalfa for dairy cows, we could design a good transition for the people involved in that industry now. But we don’t make those choices, so we can’t design programs to make the transition to a more extreme climate more gentle for people. We just try to keep spreading the water thinner.”

But who could make those societal decisions? Who could be we?

Protesters in marches like to chant a call-and-response: “Tell me what democracy looks like! This is what democracy looks like!” Well, this is what democracy really looks like. We’ve voted in some people who protect the fish, others the farms, and still others the cities.

Perhaps all the gridlock is supposed to exist. That’s one conclusion historian Robert Kelley reached from his study of flood control in the Sacramento Valley. “The people of the Valley pursued their long learning process within the framework of a Madisonian constitutional system,” Kelley wrote in 1990. “In that arrangement, unique to the American republic, power, conceived by the American people to be the common enemy, was broken up, dispersed, coop’d and cabined in by bills of rights, and fettered by divided and competing powers between branches of government, as well as by a triumphant national faith in laissez-faire.”

Or maybe triumphant faith in anything is an ethos for a different time. In a landscape as massive and manipulated as California’s, water issues fragment even the most potent special interest groups. Farmers might be a single, symbolic category in the state’s politics, but the current water crisis doessn’t pit farms against cities, but the agricultural interests of the San Joaquin Valley against the smaller, historic farms of the Delta. Instead of a sweeping Brownian solution — a statewide water management scheme aimed at pleasing everyone — the best answer may be a collection of small fixes. “Most of my preferences can be summed up as managed retreat,” On the Public Record told me.

No one else is willing to name this strategy, though many seem to see it as inevitable. And it may be precisely what yields the best outcomes. Centralized planning and megaengineering would be replaced by innovation throughout the system as the state slowly unwinds its commitment to sending water from north to south through an ecosystem that can no longer take the strain. We are slouching towards the future and the end of a certain kind of grand California ambition.

This story first appeared on The Atlantic as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

This story first appeared on The Atlantic as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.