If we learned anything from The Day After Tomorrow, it’s that disruptions in ocean currents lead to flash-frozen people on Madison Avenue and wolves prowling beached tanker ships in New York City.

OK, so the climatological apocalypse portrayed in the 2004 classic may not actually be how it’s all going to go down. But a new study on Antarctica’s Weddell Sea shows that global warming is messing with the motions of the ocean.

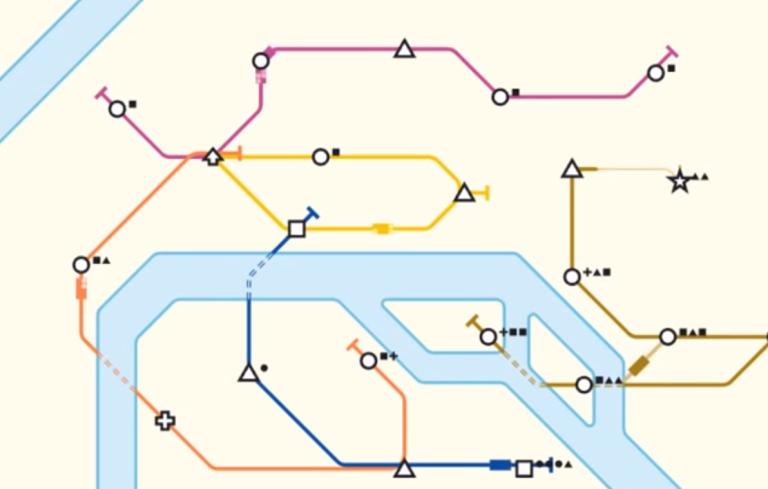

Researchers have been scratching their heads at the disappearance of the coldest, saltiest seawater over last couple of decades. Historically, this “Antarctic Bottom Water” originates in the Weddell and Ross Seas when it cools in polynya — areas of open water in which sea ice does not form — and then sinks down into the deep. After, it roams the Earth on a sort of “ocean conveyor belt,” taking almost 1,000 years to return from where it came, distributing yummy nutrients (at least I imagine they taste good if you’re plankton) and helping to keep the Earth’s climate in check along the way. But scientific sleuths think they’ve now solved the mystery of the vanishing waters: Climate change is causing more precipitation over the southern ocean, shutting down the normal mixing process.

Why? Because of density. Normally, the Weddell Sea’s surface waters are denser (because they’re colder, thanks to cooling off in the polynya) than what’s below, causing them to sink down and form Antarctic Bottom Water. But now, the increased renewal of super-fresh stuff keeps the Weddell Sea’s surface water density low, so it just stays on top instead of replenishing the Antarctic Bottom Water stores below. “I like to say it’s like a bottle of Italian salad dressing — so it separates between the dense stuff underneath and the less dense stuff on top,” says Eric Galbraith, assistant professor of Earth System Dynamics at McGill and coauthor of the new paper.

The Weddell Sea is particularly sensitive because there’s already historically less of a density difference between the layers of water. “That makes it very sensitive to a little bit of freshening at the top,” he says. “It was just kind of poised on this knife edge of whether or not it was going to make this column mixed.”

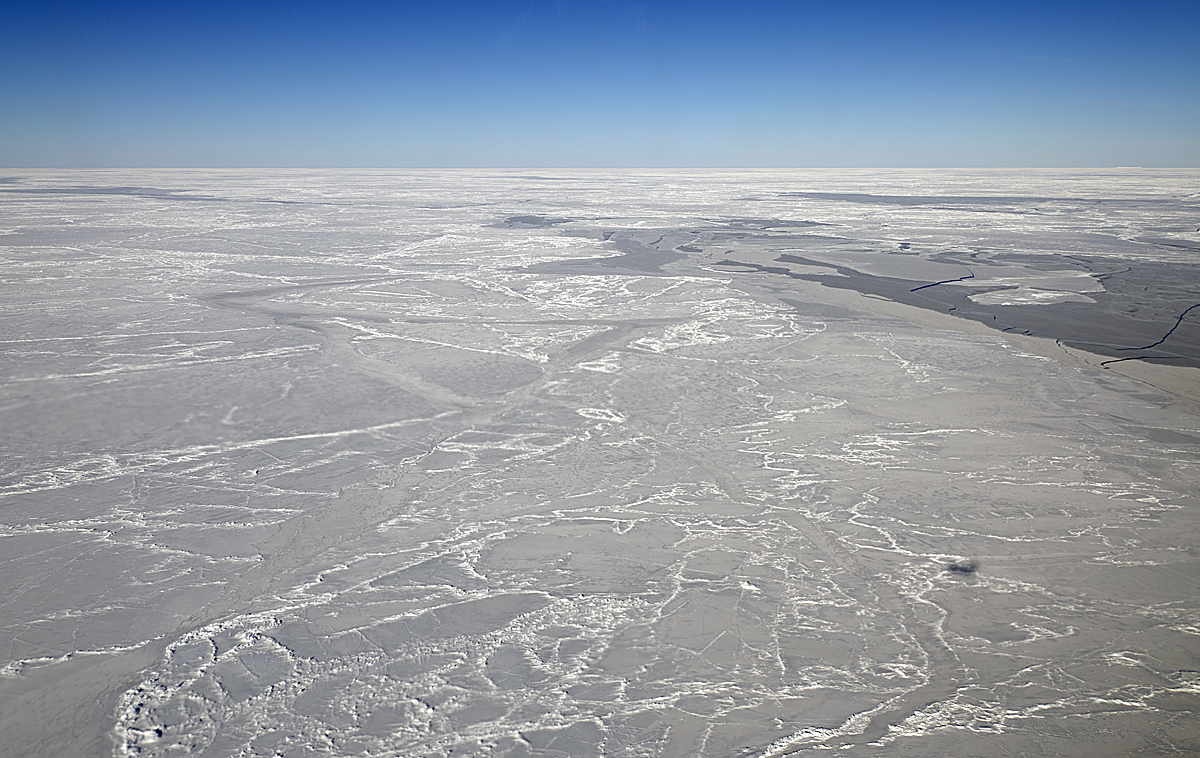

Galbraith and his team, headed by Casimir de Lavergne, think the reason behind the disappearance of the big polynya in the Weddell Sea is also related to changing currents; it’s why the Weddell Sea has been mostly hidden by an icy blanket in recent years. In the past, when the surface waters sunk down in the Weddell Sea, slightly warmer water came up to replace it — at one degree Celsius probably still not swimming temps (burr), but warm enough to ward off the sea ice. Now that the mixing’s not happening, the polynya has disappeared.

Which just means that we’ve hit on yet another way that climate change is shaking things up. Or, in this case, not shaking things up. “Really, the study is just saying, ‘Hey, wait a second, isn’t this funny that the polynya never came back after 1976?’” Galbraith says (Golly! Not the polynya!). “And all of these pieces are suggesting that an increase in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is preventing it.”

And it’s also preventing that good ‘ol Antarctic Bottom Water from doing it’s thing — which includes helping stabilize a warming climate. Scientists can’t really predict what will happen if Antarctic Bottom Water goes away forever, but if you end up next to Jake Gyllenhaal and being chased by wolves in a thousand years, don’t say we didn’t warn you.