Greg Thompson / USFWSDamaged homes along New Jersey shore after Hurricane Sandy.

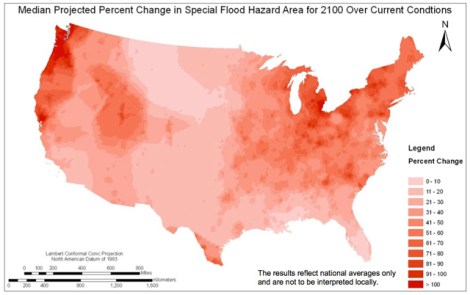

Rising seas and increasingly severe weather are expected to increase the areas of the United States at risk of floods by up to 45 percent by 2100, according to a first-of-its-kind report released by the Federal Emergency Management Agency on Wednesday [PDF]. These changes could double the number of flood-prone properties covered by the National Flood Insurance Program and drastically increase the costs of floods, the report finds.

The report concludes that climate change is likely to expand vastly the size and costs of the 45-year-old government flood insurance program. Like previous government reports, it anticipates that sea levels will rise an average of four feet [PDF] by the end of the century. But this is what’s new: The portion of the U.S. at risk for flooding, including coastal regions and areas along rivers, will grow between 40 and 45 percent by the end of the century. That shift will hammer the flood insurance program. Premiums paid into the program totaled $3.2 billion in 2009, but that figure could grow to $5.4 billion by 2040 and up to $11.2 billion by the year 2100, the report found. The 257-page study has been in the works for nearly five years and was finally released by FEMA after multiple inquiries from Climate Desk and Mother Jones.

The report attributes only 30 percent of the increased risk of flooding to population growth; 70 percent is due to climate change. FEMA designates what are known as special flood hazard areas, where there is a 1 percent risk in any given year of a major flood occurring. (They’re also known as 100-year floodplains.) If you have a federally backed mortgage on your home and it’s in a special flood hazard area, you are required by law to carry flood insurance. As of 2013, the NFIP insures 5.6 million properties. But that number could double by 2100, to as many as 11.2 million, the report found.

Having to insure twice as many properties would be a big deal for the NFIP. It generally works like any other insurance program, using the premiums that policy holders pay in each year to cover losses when they occur. But the program has been walloped by major storms in the past decade. The NFIP went $16 billion in debt on Hurricane Katrina and after Sandy will be $25 billion in the hole, a debt it may be unable repay. The report projects that the average loss on each insured property could increase as much as 90 percent by 2100. If future storm victims aren’t forced to eat their losses, taxpayers may have to cover the difference.

The FEMA study is based on the assumption that sea levels will go up by four feet in the next 86 years. But a report released last year by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration noted that sea level rise could be more than six feet. Whether it’s four feet or six feet, rising seas cause shoreline erosion and recession, and create greater surge risk in the event of major storms. The FEMA report also notes that flooding around rivers will likely become worse in a warming world, due to changes in precipitation frequency and intensity. Population growth, which causes increases in paved areas and changes in runoff patterns and drainage systems, will affect the amount of flooding from rivers, the FEMA report notes.

The FEMA findings paint a grim picture for an insurance program that is already debt-laden and is one of the largest fiscal liabilities for the U.S. government. The projections for climate costs make it appear much less likely that the program will ever be fiscally sound without significant changes. The report warns that future payments from the program “may be larger than the NFIP’s current funding and borrowing structure accommodates.”

Climate change has been conspicuously absent from the formulation of FEMA’s projections. But this report finds that climate change is a major driver of increased flood risk, and FEMA is expected to start considering climate change as it draws up maps highlighting areas that could face future flooding.

Climate change will likely make flood insurance much more expensive for the federal government, but also for individual policyholders. Right now, a number of homeowners who get their flood insurance from the federal government pay subsidized rates. But for the program to stay solvent, the average price of policies would need to increase by as much as 70 percent to offset projected losses, according to the FEMA report. That means individual policyholders who now pay an average rate of $560 per year could have to pay as much as $952 per year by 2100.

The report, which was put together by the consulting firm AECOM, stated that it is intended to serve as a “scoping-level study” and is not a set of policy recommendations. The point is to “serve as the foundation for more refined analysis as the science of climate change advances.”

This story was produced as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

This story was produced as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.