This story was originally published by Mother Jones and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency wants states to do a better job planning for the natural disasters they are likely to face in a warming world. Beginning next year, the agency will require states to evaluate the risks that climate change poses to their communities in order to gain access to millions of dollars of disaster preparedness funding.

Environmentalists are praising the plan. But some on the right are furious, claiming that the Obama administration is seeking to punish states whose governors dispute the overwhelming scientific consensus that humans are warming the planet. “FEMA toys with denying disaster funds for states that doubt global warming,” warned the Drudge Report.

The new requirement won’t affect the post-disaster relief that communities receive after being devastated by hurricanes or tornados. Rather, the change comes as part of FEMA’s revision to its State Hazard Mitigation Plan guidelines. Under its Hazard Mitigation Assistance program, FEMA allocates disaster preparedness funds to states that submit formal documents outlining the risks their communities face and how they plan to address them. These efforts might include purchasing flood-prone properties to prevent future losses, building air-conditioned refuges for major heat waves, or creating procedures for shutting down or moving equipment in a floodplain.

The revised guidelines require states to consider the impacts of “changing environment or climate conditions” in order for their plans to be approved for funding. The guidelines further explain that “the challenges posed by climate change, such as more intense storms, frequent heavy precipitation, heat waves, drought, extreme flooding, and higher sea levels could significantly alter the types and magnitudes of hazards impacting states in the future.”

Experts on climate adaptation and disaster mitigation say the new rule will help states protect their residents. “It’s an important way to get states to think about the risks and vulnerabilities they face from natural disasters and the contribution that climate change makes to increasing the frequency and scope of natural disasters,” said Rob Moore, a policy analyst for the Natural Resources Defense Council, who has pushed for this change for several years. “It should have a big impact.”

Michael Gerrard, who directs the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia University, agrees. “A state that does not include climate-related impacts in its emergency planning will be closing its eyes to one major cause of extreme events and not fully protecting its population,” he said.

But the provision could put many climate-skeptic governors—especially those from the disaster-prone Gulf states—in a tough spot. The new guidelines also require the state’s “highest elected official” to formally sign-off on the plan in order to “demonstrate statewide recognition” of the its contents. According to information compiled by Think Progress, at least 13 governors of U.S. states deny the existence or risks of human-induced climate change, including possible GOP presidential candidate Mike Pence (Ind.). The requirement might also force other likely Republican presidential candidates who have frequently avoided talking about climate change—such as Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker, Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal, and New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie—to begin confronting the issue. (Though Jindal’s and Christie’s terms will end before the next versions of their states’ plans are officially due.)

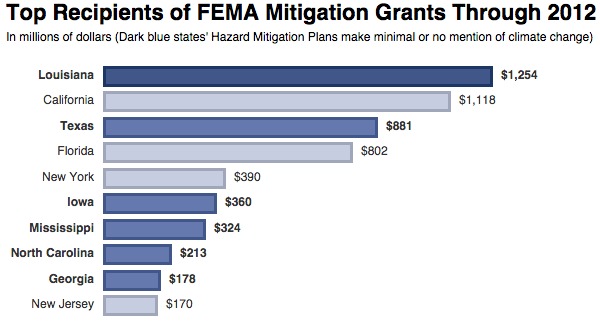

Many of the top recipients of FEMA’s disaster preparedness funding don’t adequately address climate change in their current plans. Twenty-nine states made no mention or minimal mention of climate change in their mitigation plans, according to a survey done by Gerrard’s group at Columbia in 2013. That included more than half of the top 10 recipients of the funding. In other words, these states could be spending millions of dollars of taxpayer money on emergency planning based only on historical climate data, which, as the Columbia report says, “is and will be less effective and less efficient.”

Mother Jones/NRDC/FEMA/Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia University

Interestingly, Florida—whose governor, Rick Scott, is a vocal global warming skeptic—does a better job than many of its neighbors, according to Columbia’s report. The Sunshine State’s plan acknowledges that its residents will be impacted by climate change more than other states and emphasizes the risks of sea-level rise. Still, the report faults Florida for failing to address other potential climate threats, like droughts and heat waves.

Some states, such as Texas, have added or strengthened their discussion of the impacts of climate change since the Columbia report came out. Texas’ plan now mentions that global warming contributes to sea-level rise. North Carolina, on the other hand, has moved in the opposite direction. Its 2010 plan contained an entire section describing the effects of climate change and sea-level rise. That information was omitted from its 2014 plan.

Going forward, if states refuse to acknowledge climate change in their plans, they could lose millions of dollars in funding. Gerrard also points out that states could face lawsuits if they ignore mandates that could have reduced the impacts of a disaster.

Jindal, whose state is the top recipient of hazard mitigation grants, has already spoken out against the new requirement. “This preparation saves lives,” he told the Washington Times. “The White House should not use it for political leverage to force acquiescence to their left wing ideology.”

But even some fiscal conservatives argue that if states did more in the way of climate preparedness and adaptation, billions of dollars could be saved. And a 2007 Congressional Budget Office analysis showed that for every dollar spent on disaster preparedness and mitigation, three dollars are saved in disaster recovery. Other studies show even more savings, according to Eli Lehrer, president of the conservative R Street Institute.

“Incorporating climate change into plans will pay dividends,” said Lehrer, who also supports a carbon tax. He adds that regardless of climate change, spending more on disaster preparation and mitigation often makes the most fiscal sense.

But Congress’ unwillingness to appropriate adequate federal funding has caused FEMA to make budget cuts each year, which often affects mitigation funding. According to Taxpayers for Common Sense, FEMA’s 2014 budget included $165 million in funding for pre-disaster mitigation programs; that’s 2.6 percent of the amount allocated for post-disaster relief. (To be fair, some post-disaster funds that are not part of FEMA’s annual budget are used to prepare for future disasters, as well.) “Congress seems to enjoy the drama of shoveling bucketfuls of disaster aid out in the wake of a disaster rather than the less glorious aspect of careful planning and methodical action in advance of the disaster,” said the NRDC’s Moore.

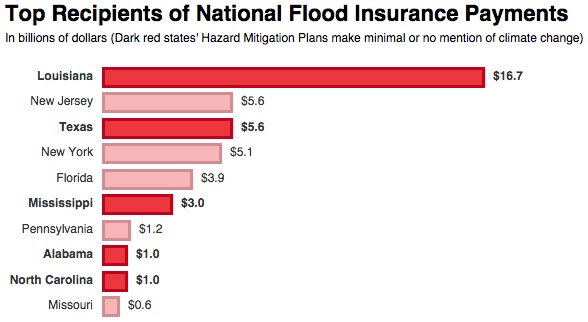

It’s perhaps not a surprise then that many of the states doing the least to prepare for climate change have received the most disaster relief money from FEMA. As of 2013, six of the top 10 recipients of National Flood Insurance Program payouts made no mention or minimal mention of climate change in their mitigation plans, according to the Columbia report. (Since then, Pennsylvania has submitted an updated plan that does address the impacts of climate change).

Mother Jones/FEMA/Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia University

Moore and Gerrard both believe that when the new FEMA guidelines take effect next year, many states will promptly update their plans, even if they are not required to do so right away (states must submit plans at least every five years). For Gerrard, adapting to climate change is just common sense. “Before 9/11, we weren’t anticipating people hijacking airplanes and running them into buildings,” he said. “Since we’ve known it’s a risk, many more protections [were] put in place and it hasn’t happened since.”