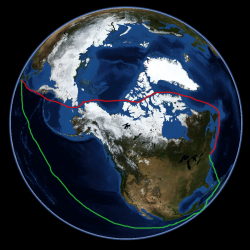

After 300 years of fruitless (and sometimes deadly) attempts to find the fabled Northwest Passage, a sea route to connect the Atlantic and Pacific oceans via the Arctic, global warming’s shown up all those hard-man sailors by suddenly making the journey easy. In 2007, higher temperatures had melted enough of that pesky Arctic ice to open the passage up to non-icebreaking vessels for the very first time, and since then the ice has only continued to melt — meaning more and more shippers will be using this efficient trade route.

But what’s good news for shippers is not necessarily good news for the rest of us: More vessels taking the northern course is also projected to spread harmful invasive species.

NASAThe Northwest Passage

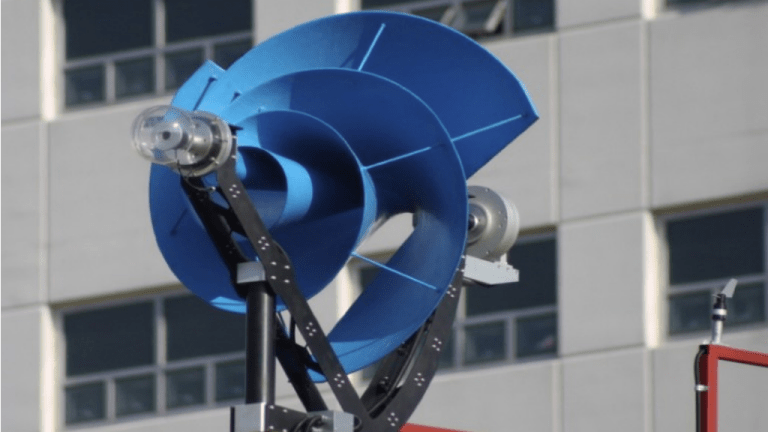

“What’s happening now is that ships move between oceans by going through the Panama or Suez [canals], but that means ships from higher latitudes have to divert south into tropical and subtropical waters,” says Whitman Miller, who recently wrote about the issue in a commentary in the journal Nature Climate Change. “[S]o if you are a cold water species you’re not likely to do well in those warm waters.” And, since freshwater flows through the Panama Canal, critters that cling on to hulls often die from osmotic shock as they go from saltwater to freshwater and back again.

But as more ships take a northerly route, the barnacles, mussels and crabs that hitch along for the journey won’t be exposed to those shocks, and so will be more likely to survive the ride.

What’s this gonna mean for our ports? The answer still unknown. But past examples of invasive species that are thought to have spread by boat, such as zebra mussels, have shown us that the damage ain’t pretty. Not only do invasives change an area’s ecology, but they cost a lot, too. Zebra mussels, which harm infrastructure like pipes, have caused billions of dollars of economic damage in the Great Lakes area.

“Invasive species are one of those things that once the genie is out of the bottle, it’s hard to put her back in,” climate scientist Jessica Hellman told Scientific American. Thankfully, if we act now there may be some ways to keep that genie in, such as requiring open water ballast exchange, and making sure that ships keep their hulls clean. Because, hey, if we’ve waited 300 years for the passage to open up, we might as well do what we can to make sure we don’t regret it.