Up to one fifth of the world’s electricity supply could come from wind turbines by 2030, according to a new report released this week by Greenpeace and the Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC). That would be an increase of 530 percent compared to the end of last year.

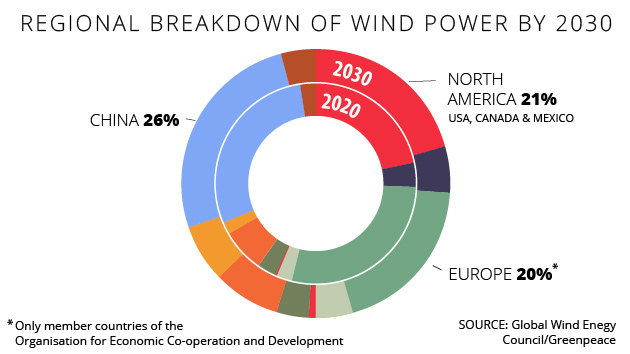

The report says the coming global boom in wind power will be driven largely by China’s rebounding wind energy market — and a continued trend of high levels of Chinese green energy investment — as well as by steady growth in the United States and new large-scale projects in Mexico, Brazil, and South Africa.

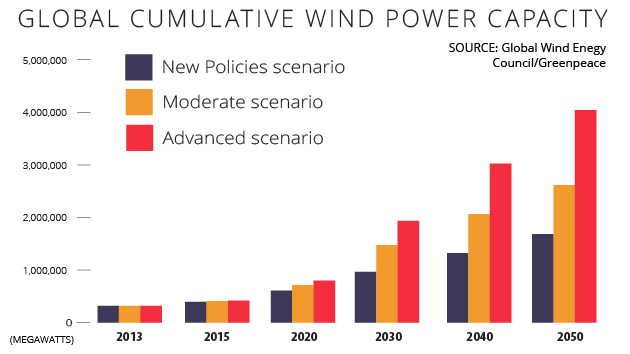

The report, called the “Global Wind Energy Outlook,” explains how wind energy could provide 2,000 gigawatts of electricity by 2030, which would account for 17 to 19 percent of global electricity. And by 2050, wind’s share of the electricity market could reach 30 percent. That’s a huge jump from the end of 2013, when wind provided around 3 percent of electricity worldwide.

The report is an annually produced industry digest co-authored by the GWEC, which represents 1,500 wind power producers. It examines three “energy scenarios” based on projections used by the International Energy Agency. The “New Policies” scenario attempts to capture the direction and intentions of international climate policy, even if some of these policies have yet to be fully implemented. From there, GWEC has fashioned two other scenarios—”moderate” and “advanced”—which reflect two different ways nations might cut carbon and keep their commitments to global climate change policies. In the most ambitious scenario, “advanced,” wind could help slash more than 3 billion tons of climate-warning carbon dioxide emissions each year. The following chart has been adapted and simplified from the report:

In the best-case scenario, China leads the way in 2020 and in 2030:

But as the report’s authors note, there is still substantial uncertainty in the market. “There is much that we don’t know about the future,” they write, “and there will no doubt be unforeseen shifts and shocks in the global economy as well as political ups and downs.” The more optimistic results contained in the report are dependent on whether the global community is going to respond “proactively to the threat of climate change, or try to do damage control after the fact,” the report says.

This story was produced as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

This story was produced as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.