This story was originally published by the Guardian and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

On a hot and lazy afternoon in Palm Beach, the only sign of movement is the water gently lapping at the grounds of Mar-a-Lago, the private club that is the prize of Donald Trump’s real estate acquisitions in Florida.

Trump currently dismisses climate change as a hoax invented by China, though he has quietly sought to shield real estate investments in Ireland from its effects.

But at the Republican presidential contender’s Palm Beach estate and the other properties that bear his name in South Florida, the water is already creeping up bridges and advancing on access roads, lawns, and beaches because of sea-level rise, according to a risk analysis prepared for the Guardian.

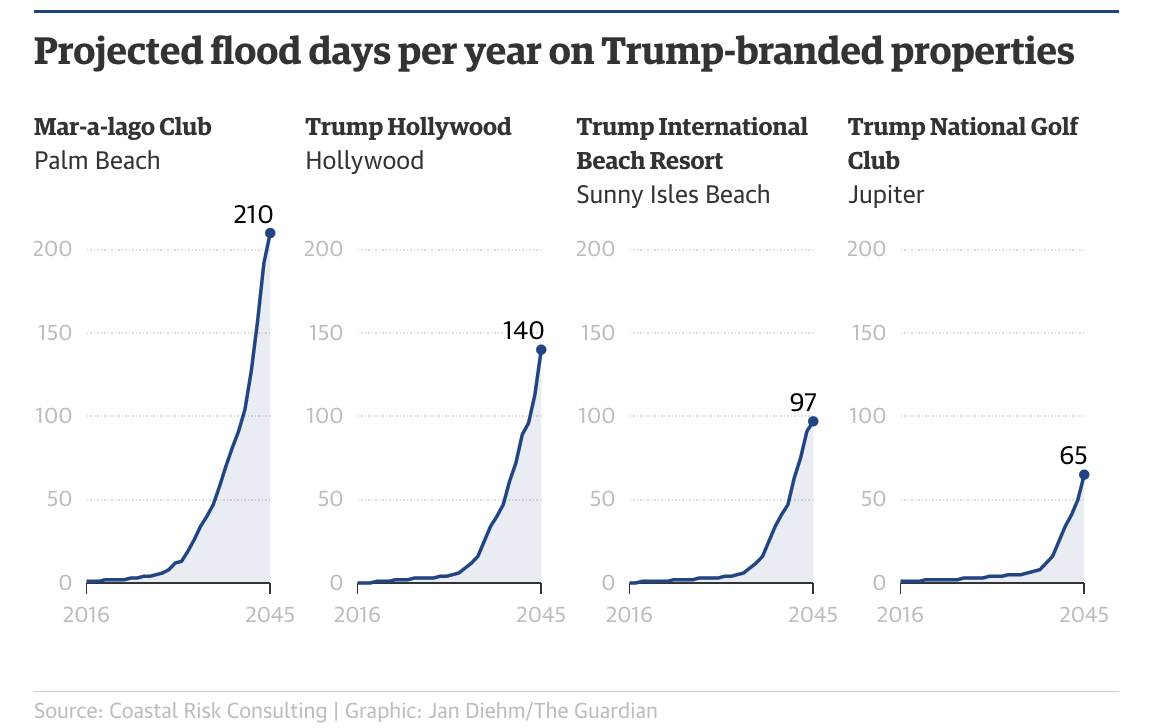

In 30 years, the grounds of Mar-a-Lago could be under at least a foot of water for 210 days a year because of tidal flooding along the intracoastal water way, with the water rising past some of the cottages and bungalows, the analysis by Coastal Risk Consulting found.

Coastal Risk Consulting/Jan Diehm/The Guardian

Trump’s insouciance in the face of overwhelming scientific evidence of climate change — even lapping up on his own doorstep — makes him something of an outlier in South Florida, where mayors are actively preparing for a future under climate change.

Trump, who backed climate action in 2009 but now describes climate change as “bullshit,” is also out of step with the U.S. and other governments’ efforts to turn emissions-cutting pledges into concrete actions in the wake of the Paris climate agreement. Trump has threatened to pull the United States out of the agreement.

And the presidential contender’s posturing about climate denial may further alienate the Republican candidate from younger voters and minority voters in this election who see climate change as a gathering danger.

When Guardian U.S. asked its readers about their most urgent concern in these elections as part of our Voices of America series, the single issue looming on their minds was climate change.

Real estate professionals, with perhaps an extra dash of self-interest, hold similar views. In a survey published in the Miami Herald last month, two-thirds of high-end Miami realtors were concerned sea-level rise and climate change could hurt local property values, up from 56 percent of them last year.

So too for mayors in South Florida. About a third of the civic leaders in South Florida’s compact of mayors are working on strategies to protect their towns from rising seas — and lobbying Florida’s governor and fellow Republicans in Congress to acknowledge the gathering threat.

Elected officials in those same Florida towns say they are already spending heavily to rebuild disappearing beaches and pump out water-logged streets.

Republicans in coastal districts can’t afford to play politics with climate change, said Steve Abrams, a Republican and mayor of Palm Beach County.

“We don’t have the luxury at the local level to engage in these lofty policy debates,” said Abrams. “I have been in knee-deep water in many parts of my district during King Tide.”

King Tides, the extreme high tides of the autumn, are a growing nuisance in Miami and other areas of South Florida — and are creeping up the manicured lawns of Trump’s Mar-a-Lago from the intracoastal waterway, according to the CRC analysis.

Parts of the estate are already at high risk of flooding under heavy rains and storms, the analysis found. By 2045, the storm surge from even a category two storm would bring waters crashing over the main swimming pool and up to the main building, the analysis found.

The historic mansion at the heart of Mar-a-Lago is not going to be underwater, “but they are going to have more and more issues with health and safety, access, and infrastructure,” said Keren Bolter, chief scientist for the firm.

Despite Trump’s pronouncements, there is strong evidence that he — personally — could pay the price for climate change in his property interests along the South Florida oceanfront and intracoastal waterway.

In South Florida, sea level is projected to rise up to 34 inches by the middle of the century and as high as 81 inches by 2100, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

South of Mar-a-Lago, where the elevation is lower, water already pools in the road in front of the Trump Hollywood condos after the briefest of cloud bursts. The luxury development, where three-bedroom units are on sale for up to $3 million apiece, offers “pristine beaches.”

“Right outside your door you’ll find the Hollywood Beach broadwalk, ranked as one of the five best boardwalks in the country,” the company website says.

But Peter Bober, a Hollywood native who is now the city’s mayor, said flooding was becoming a regular occurrence, when storms coincided with high tide.

“We have had neighborhoods where the water has been up to people’s front doors. That is not something that I remember as a kid growing up in the city of Hollywood,” he said.

Meanwhile, the city is spending heavily on pumping systems and to truck in sand to replenish beaches disappearing due to erosion.

Bober said he had seen storms with water pouring over the sea walls of the intracoastal. “Water just floods the entire neighborhood, and there is nothing we can do about it,” Bober said. “We have occasional storms where we are totally overwhelmed.”

Such instances are only growing more frequent. Bolter’s modeling suggests Trump’s Hollywood condos could be turned into islands for up to 140 days a year by 2045, cut off from the low-lying A1A coastal road because of tidal flooding and storm surges. Under a category two storm, a storm surge could wash right up to the front gate.

Further south, the Trump Grande in Sunny Isles also faces a soggy future, according to the projections. In 30 years, the boundaries of the property could face tidal flooding and storm surges for 97 days a year, cutting off access to the A1A road. The beaches could also be scoured away by erosion.

“The big issue here is that if a big storm hits, you have five-foot, six-foot waves, and that is going to eat away even at the grass here. It could push the waves even to where we are standing. And if that is going to eat away this whole area, that could do some serious damage,” Bolter said.

Other Trump-branded properties, such as the golf clubs in Doral and Jupiter, are at higher elevations, above the water line amid projected sea-level rise this century. But Bolter said the courses faced different risks from heavy rainfall and poor drainage because of Florida’s high water table.

Scientists have long expected sea-level rise on the southeast Florida coast to occur faster than the global average, advancing rapidly on barrier islands and beaches.

The low-lying coastal areas are exposed to an additional threat of inland flooding from the intercoastal waterways, and contamination of fresh water supply by high tides and storm surges.

But the pace of sea-level rise has accelerated over the last decade because of the collapse of ice cover in Greenland and Antarctica, and because of the weakening of ocean currents such as the Gulf Stream. Nowhere is this as evident as in South Florida.

Since 2006, the average rate of sea-level rise in South Florida has increased to nine millimeters a year from three millimeters a year, for a total rise over the decade of about 90 millimeters, or about 3.5 inches, according to Shimon Wdowinski, a research scientist at the University of Miami.

As a result, flooding in Miami Beach and other low-lying areas has doubled over the last decade, Wdowinski found, using tide gauges, rain records, insurance claims, and other data to construct the flood record. “People should be aware of where they want to invest for their properties,” he said. “I think for the next 20 years it will be OK, but I don’t know if it will be in 50 or 80 years. That’s a different story.”

Other sections of the low-lying South Florida coast are just as vulnerable. In 2012, Hurricane Sandy barely grazed Florida, reserving its fury for New York and New Jersey.

But a subsequent storm unleashed huge waves that uprooted traffic lights and street signs, and caused the collapse of a 1.5-mile stretch of the A1A coastal artery in the center of Fort Lauderdale.

“When the road collapsed, that was basically a huge wake-up call,” said Jason Liechty, environmental projects coordinator for Broward County. “Sometimes when you talk about climate change and sea-level rise it seems very abstract, but if you see big chunks of concrete just sticking up out of the road, it becomes very real.

“It took $20 million and 40,000 truckloads of imported sand so far to raise the mile-long section of road by two feet, sink in metal sheets 40 feet down, and rebuild sand dunes to provide buffers from future storms — and the repairs are still under way four years later.

“So let’s do the math here: You are talking about several hundred million dollars if the whole coast line is affected, and that’s a lot of money,” Liechty said.

A number of towns in South Florida are already beginning to make the investment, calculating that it would be cheaper to put in defenses against rising seas now than wait for a catastrophe.

Miami Beach is spending $400 million to raise roads and install pumps to drain streets that experience regularly flooding at high tide — and to prevent salt water from contaminating fresh water storage inland.

In other sea-level hotspots, such as Hollywood, newer construction — including Trump-branded buildings — are being built on top of steeply graded driveways, above the flood zone.

But for some of South Florida’s cities, there may be no alternative to retreat — even if it means abandoning some of the wealthiest real estate in the country.

In his offices in the historic city hall of Coral Gables, James Cason keeps a poster-size map showing a wide swath of land, sliced up by canals, yacht moorings, and multimillion dollar homes in gated communities with elevations below four feet.

About 34 miles of Coral Gables are exposed to the ocean. The entire area — representing about $3 billion in property and about 10 percent of homes — will be underwater in the second half of the century, according to NOAA’s projections.

Two schools, 20 bridges, 21 pumping stations will all be swamped, according to the projections. Some 302 yachts will almost certainly be trapped behind low-lying bridges. Water treatment plants and pumping stations will no longer work.

Cason has no patience for those, like Trump, who deny climate change is occurring. “It’s an existential threat to a city like us,” he said. So much so that Cason has hired consultants to contemplate a future when it may no longer be able to engineer a way out of sea-level rise.

“What do you do if and when the water is up so high you can’t provide services — when do you stop charging taxes?” he asked. “If your house is underwater, can you stop paying taxes on it?”

He would like to believe that by the end of the century, scientists will have figured out a solution to the rising seas that threaten his city. But there is one thing of which he is certain: Coral Gables will not survive by retreating behind a sea wall.

“There is no Dutch solution,” he said. “You can’t really build a wall around it. It will just come up from below.”