Bali is an undeniably sexy place, and anyone who tries to tell you otherwise should not be trusted on any matter. Everything is lush, steamy, and fragrant. The primary activity for the vast majority of those visiting the island is basking in the sun in varying states of nudity. In full disclosure, I spent a significant portion of my time there in a state of deep regret that I wasn’t there with a guy. (Shout out to my seat partner on the flight from Seattle to Seoul, with whom I had the following exchange: “Oh, you’re headed to Bali? What for?” “I’m going for work.” “Isn’t that where everyone goes on their honeymoon?” “… Yep.”)

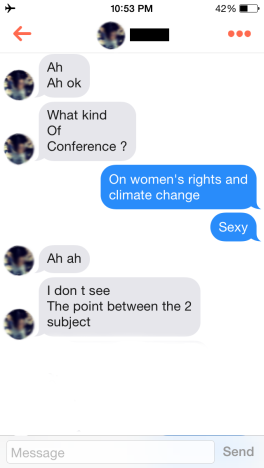

It’s a place where physicality is almost always on the brain — which is why it almost makes perfect sense to host the first Summit on Women and Climate, a collaboration between Global Greengrants, the Greengrants Alliance of Funds, and the International Network of Women’s Funds. But I’m aware that the connection there is not readily apparent to everyone, as noted in an exchange with a French denizen of Tinder (downloaded for research purposes only, of course):

Women’s bodies, however, are smack on the front lines of combat against climate change. This is what we know: Climate change is going to fuck everyone over, but it will especially fuck those who are already socially and economically disadvantaged, because it’s just that kind of adversary! And for indigenous women — particularly in developing countries — threats to their environments constitute direct attacks on their physical, social, and economic health.

“For indigenous women, the relationship with the environment is very important – it has such a high impact on [their] lives,” says Mariana Lopez, program coordinator for the International Indigenous Women’s Forum. “They have a very close relationship with the cycles of nature. But with climate change altering those patterns — well, when nature is unpredictable, it’s very disruptive to their lives.”

In terms of environmental threats, it’s hard to get more daunting than the relentless increase of global temperatures. Here’s the other thing about climate change: In many places it’s already gone from threat to reality. And in those places, women are suffering the impacts of that reality moreso than their male counterparts for a variety of complex reasons I’ll get into later. Furthermore, their lack of a voice in decision-making processes is guaranteed to only compound that suffering.

The need for women’s voices to be heard becomes most vividly apparent when considering the fact that indigenous women are struggling to protect and retain control of the very natural resources that they depend on — which are directly threatened by climate change.

“We are seeing a sort of ecological violence that highly affects indigenous women,” Lopez tells me. “The damage that corporations are inflicting on natural resources have an impact on the life of indigenous women — a very, very direct impact. We see a lot of sexual and reproductive health problems specific to indigenous women — and not men — that are linked to pesticides, toxins, contamination of water. If environmental rights are not guaranteed, the human rights of indigenous women are not going to be guaranteed, either.”

I may talk a lot of game about dealing with climate change as a woman. But as a white, city-dwelling American, I almost never have to confront its effects in my daily life (at least for now). So if you’d like to hear war stories, I’m really not the one to ask.

Instead, ask Ursula Rakova, executive director of Tulele Peisa, who is in the process of relocating her entire community from the Papua New Guinean island of Tulun to the nearby island of Bougainville. Why would someone go to all that trouble? Because Tulun is slowly disappearing into the sea. Oh.

Eve AndrewsUrsula Rakova.

Rakova, like many other of the summit delegates, occupies an important role. As a woman in her community, she is primarily responsible for every aspect of food provision: farming, fishing, foraging, preparation. Because Tulun has been slowly eaten away by an invading ocean, the arable land is gone; the soil has been soaked in salt water. Nothing will grow except rice, which is not part of the traditional diet. The traditional staple of taro has died off from Tulun completely.

“Women are now being forced to do more physical work because they’ve got to find food,” she tells me. “And when they find the little food that they can, they give it to their children. They go without food almost every day. It is the women on the island who are suffering more of the impact [of climate change] than anyone else.”

Nearly 40 years ago, the Tulun community noticed that the ocean began to eat away at the shores of the island.

“We knew that something was happening to the island,” she says. “Although we did not really understand the science of climate change, we could see before our eyes that the islands were getting smaller, and the storms were more frequent, the king tides were frequent.”

In the early 1990s, experts began to visit Tulun to study what was happening to the island, and explained to Rakova and her community that they were being directly affected by rising sea levels. “That was when we started to read about what was causing climate change,” she says. “And then we started to realize: We are victims of something we have not created – of some other people’s doing.” She pauses and then adds: “But then we also know we cannot blame anybody. It’s a global issue, and everyone has to make an effort to solve that issue.”

Mama Aleta Baun and I are sitting opposite each other in an enormous bamboo hall on the grounds of the summit. It’s about 95 degrees and humid, and through a heavy heat-and-jetlag haze I’m trying to register some facial responses to what she’s saying — however, because she’s speaking in Indonesian through an interpreter, everything is on a 30-second delay. She is very calmly describing the physical attacks that she’s endured in the name of defending her community’s lands against a mining company’s interests. I’ve seldom felt so out of my element.

“According to Timorese philosophy, the Earth is considered our mother,” Baun tells me. She was awarded the Goldman Prize in 2013 for her work in blocking a mining development in West Timor that would contaminate her people’s water supply. “The soil represents the body, the water is the blood, the rocks are the bones, and the forests are the air. When one of these elements is destroyed, it creates an imbalance in the Earth.”

For the average young cynical westerner (hi!), the “Mother Earth” trope has essentially become a punch line — a standby in the vernacular of the outdated and clueless. But the concept carries renewed gravity coming from a woman who has faced rape and death threats, public beatings, and even an assassination attempt by machete, all in the name of protecting the natural resources of her community.

“There is no difference between fighting for women’s rights and fighting for environmental protection,” says Baun. “They are equal.”

I asked many of the delegates the same question: What role does the natural environment play in the daily lives of women in your community? Each time, the question was met with the kind of side-eye that transcends spoken language to say: Do you really need me to explain something so basic? For each of these women, natural elements — forests, rivers, oceans — form such inextricable components of their health and livelihoods that to explain how they are seems an exercise in stating the obvious.

But for those of us who look no further than Whole Foods for our next meal (hi again!), this relationship is not necessarily that easy to conceptualize. When I asked this of Suryamani Kumari Bagat, who is fighting for the land rights of the indigenous peoples in India’s Jharkhand Forest, she all but laughed at me.

Eve AndrewsSuryamani Kumari Bagat is defending her community’s right to control the Jharkhand Forest, which they call home.

“The relationship? It’s like your heart and soul are connected with the forest,” she says. “A woman’s entire day is spent in the forest, and for many things … but it’s mostly about food and survival. And if we don’t eat food, how will we live?”

Bagat told me how women in her community have already noted irregularities in the forest cycles over the last five years. Leaves don’t fall when they’re supposed to. Migrating birds are showing up at odd times. Periods of drought have become far more frequent.

I asked her whether these changing patterns made her and her community anxious for the health and longevity of the forest. Again, she laughed at me. For Bagat, climate change may be a persistent worry, but the more immediate threat lies with the mining companies that are determinedly encroaching on her lands.

“Our fear is that [mining companies] will come and take the land away,” she explains. “The government is giving away the land to these companies as if it’s their own father’s land, but it’s not – the land is ours. And the mining will ruin the forest, our culture, our life, our livelihoods. So that is the biggest fear: how will the mining ruin the natural surroundings. Our whole life would be finished.”

There’s a lot of talk about the role that indigenous peoples’ protection of resources — specifically forests — can play in mitigating climate change, including a report released just last month by the World Resources Institute. As Lorena Aguilar, senior advisor for the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Gender Program, explained at the summit this week: “Indigenous women are implementing actions to adapt to and mitigate climate change, because they’re aware of how to manage natural resources and ecosystems.”

Fair. But in talking with these women, these actions might not be with the express goal of mitigating climate change. Rather, they’re reclaiming and protecting what’s rightfully theirs — not just as a matter of rights, but as a matter of survival.

Says Bagat: “If we have ownership of the resources of the forest, then the right to life is ensured.”

Berta Cáceres is the general coordinator of COPINH, an organization that has been fighting for control of indigenous lands for the Lenca people of Honduras for more than 20 years. Just last fall, COPINH defeated a hydroelectric dam that had been illegally installed by the Honduran corporation DESA in the Gualcarque River. “It’s a place of very potent spiritual and cultural meaning for the Lenca people,” says Cáceres.

“We’re not just fighting for the forests, the Earth, our lands,” she explains. “We consider the defense of issues of land, sovereignty, and independence to be the same as defending our rights as women. We’re demanding control over our lands just as we demand control over our bodies.”

Eve AndrewsFor her efforts to block a hydroelectric plant on a river sacred to her community, Berta Cáceres has been relentlessly persecuted and threatened by the Honduran government.

As a result of her work, Cáceres says she and her colleagues (who are both men and women) have been the target of armed assault, death threats, rape threats, and highly orchestrated smear campaigns involving falsified Twitter and Facebook accounts. These aren’t only perpetrated by DESA, but also from the Honduran government, which has supported a slew of extractive industries in the country for decades. The government has actively refused to recognize the illegality and illegitimacy of building hydroelectric dam projects – and there are 17 more in the works – on indigenous lands.

I asked Cáceres if she feels that her position as a woman makes these attacks more extreme. “I’m absolutely convinced that if I were a man, this level of aggression wouldn’t be so violent,” she said. “There are always campaigns against leaders, but when we are women leading … this fight defending nature as a public good, and also reclaiming our right to sovereignty over our bodies, thoughts, and political ideals, our cultural and spiritual rights, of course the aggression is much greater.”

As we’ve seen, indigenous women tend to be excluded from the policymaking conversation around protecting natural resources in a warming and increasingly overcrowded planet. For a concrete example of that irony, just ask Ursula Rakova what she thinks the biggest obstacle to her mission of moving her community from Tulun to Bougainville will be.

“[It] is the lack of recognition by the Papua New Guinea government and Bougainville government,” she says. “They have got to realize that this is happening, that they are responsible for supporting [relocating the community.] They cannot continue to work on the policy, they cannot continue to talk about planning, when people are already suffering.”

A small sliver of hope: This September, the United Nations will host its first ever World Conference on Indigenous Peoples, bringing together organizations and community leaders from around the world. Mariana Lopez tells me that one of the main points of discussion will be the issue of environmental violence against indigenous women, and also how they can participate in political processes to combat it. In an astounding failing of bureaucracy, however, it just happens to be taking place on the exact same day — in the same building, no less — as Ban Ki-Moon’s Climate Summit.

“I don’t know whether it’s funny or sad,” says Lopez. “But it’s not very good for indigenous peoples. The high-level government delegates are going to go to the Climate Summit, so the World Conference will have less visibility. It’s a joke, because we spent so many years pushing for the World Conference, and this will be the first time [that it’s happening.]”

An enormous, sloth-paced international organization made some questionable scheduling decisions and ended up screwing over an underprivileged group. No surprises there! But it does make for a fairly stark metaphor of indigenous women’s role in the global climate change conversation: closed off from a discussion amongst high-profile political figures about a global force that will completely and inevitably impact their lives.

When I asked Berta Cáceres how she considers the role that women — particularly indigenous women — will play in fighting climate change, this was her response:

“We have to change the system, not the climate, right? I think that we, as women, are in a very important moment right now, politically and historically speaking. Now is the era of women.”

For the sake of the planet, let’s hope so!

3/3/2017: This post has been updated to reflect the correct spelling of Berta Cáceres’s name.

UPDATE: On March 3, 2016, Berta Cáceres was assassinated in her home in Honduras for the efforts to defend her land described in this story.