Imagine 2200, Grist’s climate fiction contest, celebrates stories that offer vivid, hope-filled, diverse visions of climate progress. Discover all the 2024 winners. Or sign up for email updates to get new stories in your inbox.

It was a typical Thursday, except for the potatoes. Dario and Vin stared down at the heap of them: crispy hash browns here, grilled home fries there. A half-dozen peeled spuds sat in a bucket of cold water, waiting for a turn that wouldn’t come.

“Huh,” Vin said.

“Huh,” Dario agreed.

“I don’t think this has ever happened before,” Vin commented.

“Not while I’ve worked here,” Dario concurred.

“So what do we do with … ” Vin gestured. It was a little helpless, a half-limp sweep of the sheer volume of uneaten potatoes in the kitchen.

Zinnia poked her head in from the front-of-house. “Honestly,” she said. “Am I going to have to come back there? It’s turnover in, like, 20 minutes.”

“Nobody ordered potatoes,” Dario told her. “Like, at all. All day.”

“No fries,” Vin said.

“No hash browns,” Dario said.

“No baked,” Vin added.

“No roasted,” Dario said, starting to smile.

“No scalloped.”

“No mashed.”

“No chips.”

Dario grinned. “Oooh, good one. Here: no latkes.”

“Damn!” Vin said. “No gnocchi.”

“No gratin.”

“No salad.”

“No hassletop,” Dario said, and Zinnia clapped her hands to get their attention.

“It’s hassleback, children! Seriously, how are you cooks?”

Vin flicked a fry at her. “Pretty sure we’re both older than you, fingerling.” He threw a fry at Dario, who caught it in his mouth.

“No fingerlings!” Dario said, around the fry. It was salty and perfect.

“Half that stuff’s not even on the menu. We can leave it for the Lux,” Zinnia said, but she sidled over to shovel fries into the prodigious takeout pouch on her purse.

“The Lux don’t do potatoes,” Vin said.

“Nothing potato?” Dario asked, incredulous.

Vin popped his shoulders up and down, and pulled out his phone. “Maybe Jay can pull a special out of the ones we peeled, but those already breakfast-ified will have to come with us.”

“Well, get to packing up,” Zinnia said. “I wasn’t kidding about turnover. We gotta hustle. You need me to help clean up back here?”

Dario shook his head. “We need you to de-potato us,” he said. “We prepped everything, like normal.”

“Didn’t know it was gonna be no-potato Thursday,” Vin said, tossing Dario another fry.

“Didn’t know it was spud Sunday,” Dario said.

Vin snorted, but he was already getting the prepared food stowed in to-go boxes. “How does that one make sense?”

“Day of rest, right?” Dario said. “But, like, for potatoes.”

“Y’all gonna be on a permanent rest, if the B team gets here and the kitchen’s not nice and shiny for them,” Zinnia said.

Dario just laughed, though he did start collecting utensils to stick in the sanitizer. “I’ll tell Jay you called them the B team, and we’ll see about that permanent rest,” he said. When she kept hovering, he realized that she was actually concerned, and changed his tack. “Look, we’re all good back here. Just swap the signs out front, and take as many potatoes as you can on the way out. We’ll be done in no time.”

He was telling the truth: Fifteen minutes later, the three of them were standing on the platform in front of the little restaurant, balancing cartons of potatoes underneath the repixelating sign. Their sluggish system was at least 10 years old, and it took a good while for Amazing Audrey’s Eggs-A-Plenty to shift over to The Luxembourg. Once the algorithm got out of bed, though, it would scrub over everything. Double-A’s had tile, while the Lux favored wood paneling. Yellow and white would be replaced by blue and brown, and the kitschy chicken paintings would flip around to black-and-white landscape photography.

Dario had seen places that had even more settings, and though he didn’t spend much time in the hyperwired underground, he’d heard there were eateries that could microcustomize down to the level of the individual table.

He toggled on their bullshit security system, mostly out of habit, and went to wait for the Leveler with the others. They were sitting out of the sun beneath the station overhang.

“I mean, I just don’t get pings from dudes in the park,” Vin was teasing.

“Shows what you know,” Zinnia sniffed. “Yeong-cheol Min? Seriously? No name recognition there at all?”

Vin leaned around Zinnia, to loop Dario in. “She says there’s an old dude gonna be in KSW Memorial. He pinged her.”

“The Arts In The Park people pinged me,” Zinnia corrected. “I subscribe, because I’m not an uncultured plebeian.”

“We’re plebs,” Vin said, with mock sadness.

“Pleb,” Dario agreed.

Zinnia continued as if they hadn’t interrupted, which in Dario’s opinion was a fairly sound strategy. “Yeong-Cheol Min is, like, the greatest living artist of our time, at least in the field of pottery. It’s day four of his live performance.”

The Leveler pulled up, all shiny chrome and green plastic, and they jostled into a compartment. “So,” Dario said, “we’re going to KSW Memorial? For pottery? How do you even do a live show for pottery?”

“He takes it out of the ground,” Zinnia informed them. She paused for a second, while the automated voice reminded them to keep their limbs inside the compartment while the Leveler was in motion, and not to forget their stop. Then she continued: “Day one, he digs up a bunch of dirt, and extracts the clay.”

“I thought you needed special dirt for pottery,” Dario commented. “Special pottery clay, or whatever.”

Vin shook his head. “No, there’s at least a little clay in most soils. You never did that, in fourth grade? Filter out the clay, make your own little pinch pots? That’s like, a right of passage, man. I mean, were you even a 9-year-old, if you didn’t make a pinch pot in art class?”

“It didn’t come up,” Dario said, a little shorter than he meant it. He rearranged the cartons of potatoes in his arms, partly so he wouldn’t have to see their faces when they remembered.

“Oh,” Vin said, abashed. “Yeah, sorry, right, I mean —”

He shut up abruptly, and Dario shot Zinnia an appreciative look, knowing she was somehow behind it. She was safer to look at, just then: He doubted she had the capacity to pity him. Compassion, maybe. But pity? He couldn’t even picture it on her face.

She was poised as ever. “The first day, he digs up the dirt. Has to get a permit for it, but who’s gonna deny Yeong-cheol Min a permit? Besides, he puts almost all of it back — just keeps the extracted clay. Then, it’s got to sit for a while. Day two, he refines it some more. There’s stuff you have to do, to remove air bubbles and other impurities that could break the work once it’s fired. But then he starts working it, and that’s the really cool bit. Usually, he finishes in a day, but this one is huge. My feed is full of pictures, but I can’t tell what it is.”

He doubted she had the capacity to pity him. Compassion, maybe. But pity?

Vin asked, “So he’s finishing it today? Or still shaping?”

“Still shaping,” Zinnia said. “Maybe he’ll finish today, maybe he won’t. That’s part of what’s so exciting!”

“And we’re bringing a butt-ton of potatoes to this event because … ?” Dario inquired. “I mean, not that I was doing anything else this afternoon. But still. How is this your solution to the inexplicable potato event?”

“IPE, for short,” Vin put in. “It needs an acronym.”

“So we can eat while we watch the pottery performance,” Zinnia said, as though this were obvious. “And, like, give potatoes away. To whoever.”

Vin and Dario exchanged a look. Vin’s wide eyes said, It’s too precious, I can’t even try. The quirk of Dario’s mouth said, We’re not horrible enough to tease her over this. Silently, they agreed. Privately, Dario knew they were both going to ping Jay about this later.

“Sounds like a great plan, Zin,” Vin said, and got one of her to-go boxes added to his pile for his trouble.

“Thanks for the support, Vinnia,” Zinnia said, and they lapsed into companionable public-transit silence.

In Dario’s opinion, the Leveler was misnamed. Sure, it moved up and down between the various vertical levels of the city, but it also ran on a lateral route. Like a train, he thought. Or an elevator. A trainevator.

“Trainevator,” he said, out loud.

Vin’s eyes lit up. “Eletrain,” he said.

“Escalatrain.”

“Escelatram,” Vin shot back, and Zinnia groaned and put on her headphones for the remainder of the trip.

Ken Saro-Wiwa Memorial Park was several levels down and many blocks over from Double-A’s. They usually finished up with the late brunch crowd just in time to meet the transit rush of kids getting out of school, and this day was no exception in that regard. By the time they actually made it to the park, they’d successfully redistributed nearly a third of the potatoes.

“Hop the Parkline?” Vin suggested, as they exited the Leveler.

“Nah,” Dario said. “I feel like walking. Been standing at the griddle all morning.”

Zinnia guided them in the general direction of the art event, and a part of Dario relaxed as soon as they were under the leafy canopy. The temperature dropped immediately in this shade, and the cool of it was soothing. Bushy oaks lined every walking path, the Parkline winding unobtrusively between them.

His childhood home had had trees like this, before, though those oaks had been bendier and lichen-draped. It had been the salt that killed them even before the water, and he’d grieved them with the passion a small child can muster for such an occasion. This city was verdant, an intentionality that drew him here in the first place when he had to be resettled. But a place like this, heavy with oaks, would always speak to him in a way the vine-covered buildings and succulent-lined sidewalks just didn’t.

When they saw the crowd, Dario’s first thought was, Huh, I guess people do turn out for a live pottery show.

“I’m impressed,” Vin said, echoing Dario’s own thoughts.

“Told you,” Zinnia sang. “This is a big deal!”

Dario had never been to this particular corner of the park before. The ground sloped down into a sort of naturalistic amphitheater, full of people. The landscape created a hole in the tree cover, and the midafternoon sun poured down on the spectacle in the middle: an older man, graying hair pulled back in a scraggly ponytail, arranging heaps of reddish mud.

Dario’s first impression of Yeong-cheol Min was, I wouldn’t recognize him on the street. The artist was unobtrusive, his features unremarkable and his presentation lacking ostentation. He could have been any of the grandfathers who sat outside their doors on Dario’s street, gossiping among each other. He wore much-stained denim overalls and a short-sleeved shirt gone grayish-red from his work, and as Dario watched, he rolled the side of his own pant leg over a patch of clay, leaving behind the texture of the cloth.

“I don’t know what I was expecting,” Dario said, aloud. “This all seems pretty chill.”

The crowd around them was buzzing with the low undercurrent of conversation, and that made the scene even more approachable. The three of them picked their way through the assembled people, offering potatoes to strangers until they were left with just one container each and had arrived at a good spot to watch.

The grassy ground gave under Dario’s feet just slightly, as he shifted his weight. Vin held up his own to-go plate, and Dario helped him split their food so that they’d have an equal amount of hash browns and fries. Zinnia carried two types of hot sauce with her at all times, and they took a moment to bicker over which one was better. Then, as they ate, Dario turned his attention back to the live performance.

It was hard to assess what exactly the artist was making, but Dario wasn’t quite ready to call it abstract. The curved spires and chunky blocks seemed familiar somehow, in a way he couldn’t put his finger on. Staring at it was like getting the ghost of a tune caught in his head, too small a scrap to look up. In such a case, he was relegated to humming it under his breath, hoping to eventually chance upon a lyric somewhere in the crevices of his mind.

Min periodically returned to a box of tools, which he employed to texture the clay in places. There were sharp sticks, scalpels for carving, little wheels for adding tracks. Then, there was the artist’s own body: He rubbed his hands over the clay, sometimes dipping them in water. He turned the side of his head against a section, printing the clay with little lines from his hair. Gently, ever so gently, he brought his bare feet up to the work, and squished the clay between his toes.

The familiarity of it was getting to Dario, in a way he couldn’t express. I know this. How do I know this? He couldn’t recall having so much as heard of this artist before, much less seen his work. And, as he’d told the others, Dario had not had the kind of childhood where one was taught to play with clay. There was no obvious reason for this feeling in his chest, and he tried to push it away, uncertain.

In front of the patch of grass that Dario, Vin, and Zinnia had staked out, an older woman sat in rapture. Dario watched her watch Min, and was more than a little disturbed to see tears tracking down her face. The most unsettling thing was, he could feel the tightness in his own chest, too. He didn’t want it, couldn’t understand it.

This is a goddamn live pottery show, he chided himself. What is so upsetting about it? There’s nothing wrong here, nothing bad. What’s going on?

He turned to his friends, but they seemed unaffected by whatever was taking place. Zinnia was taking pictures, swiping through different filters. Vin was about as interested in the potatoes as he was in the artwork unfolding before him.

Dario watched for a good 10 minutes before he put it together: Min added a lump of clay, sticking it onto a wire such that it might balance at a precarious angle. Then, he added another. And another.

Archipelago. The word popped into Dario’s mind, and he course-corrected immediately: No. Barrier islands. He realized that he was looking at a stylized depiction of a coastline. His coastline. Before.

He could name them from their shape, as they appeared under Min’s hands: Cat Island. Ship Island. Horn, Petit Bois, Dauphin.

His breath caught in his throat, and the names came fast as he raked his gaze over the work, this time seeing it for what it was. Mobile Bay to the east, Lake Pontchartrain to the west. On one side, the Pascagoula River, where it curves around Moss Point. On the other side, Bay St. Louis, ringed by Henderson Point, Pass Christian, De Lisle.

He realized that he was looking at a stylized depiction of a coastline. His coastline. Before.

Dario’s eyes tracked the snarl of the Wolf River, then drifted over, almost against his will, to the looping tangle of earth and water that was where the Biloxi met the sea. In this work of art, the land was still land, worked in clay, but the water was represented by air. An absence. Not the presence that had risen, consumed.

Old Fort — we used to hunt for frogs. Davis Bayou. He watched Min shape Deer Island across the mouth of the Bay, and inside his shoes he flexed his toes, remembering the sand. Why is he doing this? How does he know?

It occurred to Dario that there were maps, that the artist could have consulted records to know this place that was. He looked for, and found, the little inlet where he’d grown up. Halstead Bayou. It would have been easy to miss, easy to exclude. A sliver of a place, an intertidal zone at the end of the world. Long-since swallowed by the insistent sea, little by little and then all at once, in a storm so great it decimated the very ground they might have rebuilt on. A shadow of Dario’s life was still there, a heat-haze of childhood memories buried in sand and rubble and water.

The water, the water, the water. His aunt used to say, It giveth and it taketh away, but Dario had hated that. It spoke to an undulation where he’d only experienced an escalation. It implied a reciprocity that he didn’t think had been present for a very, very long time before the end.

“I think it’s some type of crown,” Zinnia said. “If you cut a crown, and unwrapped it, like. You know?”

“Nah, I think it’s supposed to be mountains,” Vin said. “See all the pointy parts? And the wavy bits, that’s, like, where the rivers come down in between. You see it?”

Dario didn’t correct them. He didn’t want to explain, didn’t want to verbalize what he was feeling just yet. He wasn’t crying, but now he looked at the old woman in front of them, and thought he saw the echoes of his own family in her grief-stricken face. His grandmother had always kept her composure, at least in front of the kids. He wondered if this is what she might have looked like, in the absence of her family’s confining, bracing weight.

He didn’t know how long they watched. Long enough that Zinnia started messaging with a friend, on one side of him. Long enough that Vin got distracted feeding little bits of potato to the ants, on the other side of him. But Dario watched, and watched, and watched. Under Yeong-cheol’s hands, the world was recreated. Dario could feel the echo of mud under his own fingernails — he’d been young enough that digging through rubble was a treasure hunt on par with catching crabs, the thrill of discovery muddled in with a baseline horror not quite over his head.

Toward the end — Dario knew it was the end, could sense the completeness of it — the old man took a sharp stick. Across the bottom, he carved the words Accensa Domo Proximi.

“Oooh,” Zinnia said beside him, typing furiously with her thumbs. “OK, OK. I’m on Grapevine, and people are posting that it’s a map or something. And that would be Latin, right? Did either of you take Latin in school?”

Dario ignored her, and found himself moving through the crowd, to the very front. There was no barrier separating the artist and the assembled, the work from its watchers. He simply stepped through the people, across the short empty space they’d left by popular consensus, and found himself inches from the enormous clay representation.

Slowly, carefully, he reached out. Dario rolled the pad of his thumb over the spot where Halstead Bayou used to be, leaving behind a faint ridged whorl. Then he stepped back, all too aware of the escalating volume of the crowd and the number of cameras that were now pointed at him.

He met Yeong-cheol’s eyes, not knowing what to expect. But there was understanding there, and he came over to inspect the small mark Dario had made. “This is good, I think,” he said, speaking for the first time. His English had a very slight British accent to it. “Ocean Springs?”

“Yes,” Dario said, still unsure. His thoughts were starting to catch up to him: You touched it. One of the greatest living artists, Zinnia said! What are you doing? How could you —

What it’s like. When the death of your home is someone else’s lesson learned.

“I’m from the coast, too,” Yeong-cheol said, nodding. “An island that is no more. I’ve done several versions of it, by now. The best one is on exhibit in Seoul. This is my first attempt at your home, however. How do you think I did?”

“I recognize it,” Dario managed. He hadn’t called it home in a long time. “All of it.”

For some reason, that made the old man smile. “Good. I’m leaving it here, you know. A permanent installation, once it is properly fired. You can come visit whenever you want.” He pointed to the thumbprint, and said, “This, in particular, will make it memorable. I think we keep it, don’t you?”

Dario nodded. He would have nodded no matter what Yeong-Cheol said, but now he felt an odd sort of relief bloom in his chest. He met the man’s eyes again, and saw that same understanding even as his own thoughts came disjointed. What it’s like. When the death of your home is someone else’s lesson learned. That was by far the most grating thing about this city, for all its solar panels and biodegradable takeout boxes. He’d never been to a single memorial, even though they held them every year. A few speeches couldn’t hold the depths of the loss between their meager words, couldn’t scrape together the brokenness that had wracked that land long before the saltwater, and he’d always been uninterested in listening to people flail as they tried to do it justice aloud.

This, though? All the maps he’d ever seen had been oriented north-south, with these places on the periphery. But this representation arranged it the other way, as if the ground beneath it was the main of the continent, the features emerging up into the air at eye-level as the focus.

Dario stepped back, and back again, and suddenly Zinnia and Vin were at his side. A quick glance at their resolve told him that they might not understand what was going on, but they were ready to back him up anyways. The flowers of relief under his skin pulled at him, turned towards the warmth of their affection.

Yeong-Cheol addressed the crowd, even as he dipped his hands into a new bucket and came out with a white, viscous substance. “Accensa domo proximi, tua quoque periclitatur,” he said, as he began to gently coat the statue. “It’s unattributed, but a powerful line. When the house of your neighbor burns, your own home is likewise in danger. A millennia-old phrase, passed down through generations. And yet not something our collective human society managed to internalize, at least in certain arenas, until recently. So now, I show you: It burns.”

He produced a lighter — an old-fashioned one, that clicked as he sparked it to life. Then, he touched it to the corner of the statue, and the white liquid caught, turning flame-blue.

Some people cried out, and most everyone stepped back from the sudden heat of it. But Dario stayed put, and closed his eyes. He felt the warmth on his face, on his bare arms. His friends pressed up against him on either side, but they didn’t retreat.

The moment lasted for a long, long time. When he finally opened his eyes, the structure before him still glowed blue.

“The firing,” Zinnia said, unusually subdued beside him. “It’ll go on for the better part of the night. You want to stay and watch?” Dario thought about it. He rubbed the barest bit of clay residue between his thumb and forefinger, and took in the feeling of it, paired with the feeling of being among this crowd. Watching the sculpture with all of them felt a little like it wasn’t just his, like they were carrying this together. “Yeah,” he said, and finally retreated to a more comfortable distance. He sat, and his friends joined him. “Yeah, I think I do.”

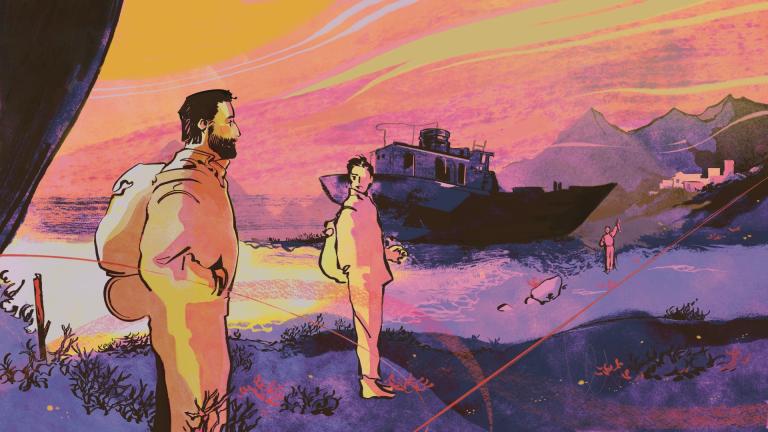

Cameron Nell Ishee (she/her) is a writer and research program administrator most recently from Vermont, whose roots include the Mississippi Gulf Coast. This is the first time her work has been published, and she celebrated with chilaquiles (the best breakfast food).

Stefan Grosse Halbuer is a digital artist from Münster, Germany. In over 10 years of freelancing, he worked for brands like Adidas, Need for Speed, Samsung, Star Wars, Sony, and Universal Music, as well as for magazines, NGOs, and startups. Stefan’s art is known for a love for details, storytelling, and vibrant colors, and has been exhibited and published all around the globe. Recently, he released his first solo book, “Lines,” a coloring book with a selection of his art from the last years.