Imagine 2200, Grist’s climate fiction initiative, celebrates stories that invite us to imagine the future we want — futures in which climate solutions flourish and we all thrive. Discover the 2025 contest winners. Or sign up for email updates to get new stories in your inbox.

Ah Kong’s crystal alerts me to an intruder while he’s plucking bean sprouts.

“About 12 kilometers from here. Large boat. Trawler,” he says, snapping the tail off another sprout.

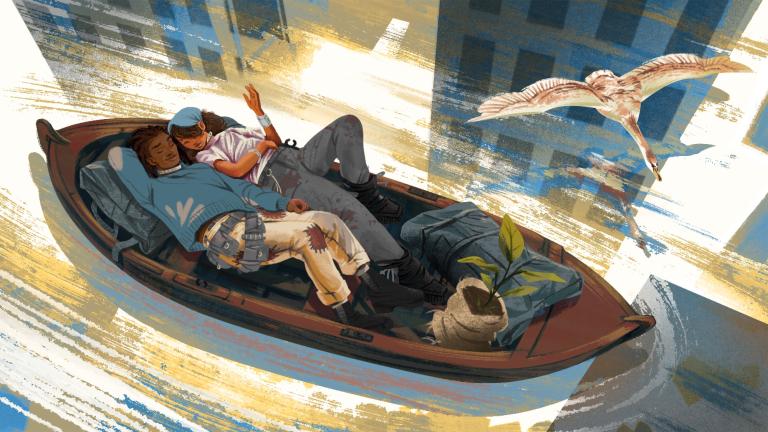

Hastily, I alert everyone on the Mousedeer over the comms. Ah Ma gets up from the lumpy bed and snarls like a feral dog. Disturbing her nap is the worst thing one can do. Moktar is inspecting some of the new reefs and is too far from us. Billy the dolphin is with his pod and they head toward the intruder.

“Don’t get caught in its net, Billy,” I warn.

“Not birthed yesterday,” Billy replies.

Ah Ma grabs up the communicator and barks at Billy. “Bring it toward the ugly rocks. Near the wreck.”

“Got you,” Billy responds.

Together with his posse, he starts herding a school of sardines. It’s too enticing for the autotrawler to ignore. It starts turning toward the swarming, shifting ball of fish, even though it’s next to the Castle, the outcropping of treacherous rocks that has sunk more ships than I have teeth.

Meanwhile, Ah Ma is strapping on the exoskeleton that makes her resemble a wayang kulit puppet.

“You know you don’t have to board it,” I say. The Mousedeer chugs closer to the intruder.

“We cannot let them steal from us,” she says. “Too many of these ghost ships roaming. They’re like cockroaches.”

“She’s stubborn,” Ah Kong’s crystal says. The workbot has moved on to peeling tapioca.

“Please focus on meal preparation,” Ah Ma says. “Never helped in the kitchen any when you were alive, so this is your punishment.”

“You cannot take down that autotrawler yourself,” Ah Kong says detachedly, scraping the skin off a tuber.

“Quiet, you,” she snaps back, irritated. Her cloudy grey hair is projecting in wild directions. Her head lowers in prayer and her waxy fingers stroke the well-worn Guanyin jade pendant around her neck.

She trudges toward the side of the boat, slapping her palm against her back like she’s working out a kink.

“You can’t win this. Not even if I was around,” Ah Kong says. The voice is louder than I’ve ever heard it, trying to be heard above the sounds of the pounding waves.

“That’s because you envy that I’m mobile while you’re stuck inside a control bead,” Ah Ma says.

Ah Kong’s crystal fades. It flashes a series of pulses as though it’s whining.

The autotrawler is about the length of two longhouses; three times as large as our boat. The weight of its net drags it around like it’s drunk. Fish flop in the huge micro-mesh net and opportunistic birds hover, picking up stragglers.

I guide Mousedeer toward the intruder. The ghost ships are derelicts, stuck in algorithmic slavery to dead tycoons, corporations, or rogue provinces. The trawler’s blossoming nets indiscriminately capture everything. They dangle in the water like a looter’s bag almost to the sea bottom, gathering anything and everything. It probably has an internal factory where robots process, clean, and fillet the fish, discarding those that don’t fit into the capture profile after they’ve been broken down, like a murderer destroying evidence.

Ah Ma takes a deep breath, drops into the water, and grabs onto the DugongBot water scooter. The water is frothing and the waves race up the sides of the ship. I’m struggling to control the Mousedeer, as waves pound the boat and slither on the deck like they’re trying to grab hold of the ship. Foam scatters in the noonday sun like shattering crystals.

“Unflagged. I do not see anyone,” Moktar says over the intercom from his schooner on the other side of the trawler.

The Mousedeer is about 400 meters away before the autotrawler acknowledges us. Through speakers, it starts to blare instructions in various languages, like a wizard trying to dismiss us.

“This ship is authorised to sail and fish in these waters. Intruders will be dealt with,” it announces, cycling through languages. I recognize Malay, Tagalog, Cantonese, and English.

Undeterred, Ah Ma reaches the side of the trawler and deploys her gecko pads, climbing onto the deck of the ship. The trawler’s warnings climb several hundred decibels, its tone of detachment now turning angry. It threatens brutal force, though how exactly it does so isn’t clear. I lose sight of Ah Ma behind a towering wave.

The incoming wave slams the trawler into the Castle. I hear the sound of something blasting from the autotrawler. Lured by fish and noise, seagulls squawk like runaway vehicle horns, trying to match their volume with the boat’s proclamations.

“It took the bait,” Billy says. On his video feed screen, the trawler’s dangling net has entangled a sunken Fin Harvester; another Ghost craft we sank nearly a year ago.

The trawler was lumbering before and now it’s slothlike, being dragged down by the unexpected load. Another wave shoves it back toward the treacherous rocks. There’s a thunderous boom as it slams. Pebbles and debris burst into the air.

I struggle to maintain control over the Mousedeer. As I try to steer it away from the Castle, Ah Ma does a swan dive just after a wave crest, plunging into the sea like a dropped arrow. If she’s caught in the ship’s nets she’ll be dissected and discarded like unwanted bycatch.

Staggered by the last impact, the ship’s algorithm eventually comes to a decision. Like a gecko dropping its tail, the trawler sheds its vast net, cutting its catch loose. The captured fish boil out, scurrying and racing to freedom. Billy and his posse snatch a few as a form of payment. We cheer, though it is subdued.

After discarding its net, the trawler starts to turn away from the rocks, though it is still being pummelled by incoming waves. It might have another spare net within its slate-grey form, but it will not deploy it here. Battered, it slinks away in defeat.

But where is Ah Ma? I don’t see her. I call out to her on the communicator. Billy does not have any visuals on her either.

“She’ll be back,” Ah Kong’s crystal comes to life and says. “She doesn’t know how to die.”

Moktar shouts, elated. “She’s out of the water. Coming toward you.”

Ah Ma spurs the DugongBot to the Mousedeer. Coughing up water, she clambers unsteadily onto the deck. Ah Kong’s workbot strides toward her and grabs her like she’s a dropped sack.

“Placed a device on it that will send fake signals … if it ever generates its net back. Let the ghost boat chase … ghosts … ” she says, heaving.

“Was it worth killing yourself over?” Ah Kong says as the workbot starts to lift the tanks off her, but she puts up a hand, telling it to halt.

“Yes,” she says. She lies on the deck to recuperate and then slinks next to me, watching the trawler disappear from view.

“The work is not done,” she says. She starts digging through a toolbox, taking out a pair of shears. “Now we have to destroy that stupid net,” she says.

“You’re not going down again,” I say.

“You know you cannot stop me,” Ah Ma says, not looking me in the eyes.

Readjusting her gear, Ah Ma dives into the waters again. Down below she snips and cuts as much of the vicious net up as possible, like a determined gardener trimming weeds. Moktar rounds up other villagers and they join in destroying the fugitive net.

After half an hour, as her tanks are running low, Ah Ma emerges back onto the boat. She looks like she just finished a marathon. Ah Kong berates her and she brushes it aside.

I bring her a cup of warm mint tea. She takes a seat, puts a leg up, and slowly drinks it.

“You know what was the most terrifying thing?” She says, her eyes staring out at the undulating water.

“What?” I ask.

“How cold parts of the ship were. When it’s so blazing hot you can cook fish on the sand and that monster maintains a cargo hold near freezing.”

Billy the dolphin is more upbeat over the encounter. ”Yah, the Pulau Mati gang has done it again!” he says, euphoric. The dolphin does a spiral and jumps out of the water next to the Mousedeer, emitting a series of squeaky whistles.

Some of his species have been bycatch, dragged into the bellies of similar ghost ships. Ah Ma says four of its pack were captured and processed and Billy stayed at the bottom of the reef for hours. “I feared it might try to drown itself,” she says.

It is near dusk before we head back to the kelong. After removing and storing her gear, Ah Ma studies the reports of damage to the reef. Finished with its work routines, Ah Kong’s workbot powers down, waiting for the next task.

I barely remember anything about Ah Kong. He passed away when I was 10, more than six years ago. He would point out a mollusk, a fish, a bird, and then tell me what was special about it. He had a scraggly goatee and a sleepy eye, and his hands were callused, with cracked nails. He always wanted to impart a sense of wonder to those little lessons, perhaps afraid I wouldn’t love the world enough.

The crystal is the same. Always indicating the species around and their unique characteristics. His voice is precisely as I remember it.

But what the crystal says has no affection. It’s shared without any real tenderness or weight, without a need for reciprocity. There is no kind smile after every sentence. The crystal is an approximation of grandfather and who he was — but I am still grateful for its presence.

Keeping busy, Billy and I converse through his work screen. His interface is a result of an experiment that never quite reached fruition. It looks like the top of his head is covered by circuitry.

Pa worked on the harness the precocious dolphin wears, and it can eject it whenever it wants. When it hovers around the kelong and squeaks, it indicates it wants to interface. Whenever it’s bored it looks for us, and it has a genuine curiosity about humans.

We sail back to the kelong, the wooden platform off the coast we call home. I berth the Mousedeer and head toward the house. Moktar is already there, his green parakeet parading around the roof.

Moktar is the seaweed and coral expert, building trellises that kelp gather on. They grow seaweed and polyps that can tolerate the baking heat of the waters. Once they’re viable, he transplants them to once bleached reefs, hoping they will grow in the wild. He’s had more failures than successes, but it never stops him.

He’s about twenty years younger than Ah Ma and used to work with Ah Kong. Point out anything on the beach — a crab, a jellyfish, a stone coated with wet grass like it’s a cheap toupee — and he’ll tell you about it. He has a pencil notebook where he jots down ideas, measurements, and notes. He spent two days turning over a Hawksbill turtle that had flipped over on the beach. “It had an embarrassed look,” he said, “like someone who stepped into something stinky and had to attend a formal dinner.”

Everyone is famished. We roast a mackerel with the vegetables that Ah Kong has chopped up along with some chilis, thanking the gods for their gift.

After the feast, Ah Ma sits down for a game of mahjong with Ah Kong, Billy, and Moktar. Billy has to use an Exobot shell to play and Ah Ma takes advantage of it. Some of the tiles have a different texture that the bot can’t detect. None of the other players know, but I’ve caught on.

The Backrub Beetle crawls on Ah Ma’s back and uses felt-covered nubs to massage the knots around her shoulders and lower back.

“Best invention ever,” she coos as the Beetle rubs at just the right spot.

“That thing has touched her several times more than I ever have,” Ah Kong’s crystal says.

Billy studies his tiles as though they are smudgy. The bot’s claw-like hands shuffle the tiles about as Billy decides on a different strategy, the air crackling with the sound of tiles crashing into each other. The bot is likely just asking Billy for permission to go ahead with its moves; knowing Billy, he’s swimming around hunting for seashells and disturbing crabs.

Ah Ma picks up a tile and throws it back into the river. Billy is distracted. He never wins, but just enjoys manipulating the bot and sweeping the tiles about like he’s cleaning windows.

“The battle today was magnificent! Magnificent!” The dolphin-controlled Exobot sways about from side to side like an ecstatic keyboard player. The card-sized screen depicting Billy’s expressions displays a tricorn-hat cartoon dolphin squinting and smiling.

Moktar, who approaches the game with mathematical detachment, wins a few games. Billy takes a couple by sheer luck. Ah Ma wins most of the games, while Ah Kong does occasionally manage to eke out one of his own.

I don’t follow the game, instead focusing on the patrol drones and making sure that all the gear is charged up. The drones report back on the development of the mangrove and wildlife. A sea eagle attacked one of the drones a while back and I’ve programmed them with new flight patterns to stay away from the raptors.

Ah Ma says. “PONG!” She flips down the tiles all together to collective groans from around the table.

“Dugong it! I almost had the combination!” Billy’s on-screen alter ego sways in consternation.

“Pay up! Pay up!” She says. The others give her bottle caps and cowrie shells.

Ah Ma gets up, grabs a coconut shell, and pours the remaining juice right into her mouth.

“All right. Lights off soon. We need to prepare for market and sharing day,” she proclaims.

Billy unlinks from the bot. It droops like a puppet whose strings have been sliced.

The Beetle on Ah Ma’s back drops off and then opens up, allowing her to slot in her feet. “Best invention ever,” she says, as the Beetle starts massaging her sore feet.

The bots are rounding up the shredded net and bringing it to the dump, where it will spend the next few decades being broken down.

There is some work she’ll never let the bots do. She’s the one who’ll pound the chilis to make her belachan. Moktar wants to get a blender, but she has proclaimed she won’t use it. With her goggles on, her stone pestle crushes the chili furiously, and the security around the chili plants is particularly tight, with planks, sirens, and a camera. The tamarinds are perfect for adding depth to the paste. I have to evacuate when she starts roasting the chili. “Make sure you watch.”

Besides that, she’s in charge of the diving gear and Billy’s interface equipment. She used to run a dive shop with Ah Kong and Pa and worked as an engineer.

The microweaver bots weave the harvested kelp together. They’re the size of spiders and were originally configured for silk, but Ah Ma has tweaked them to handle all kinds of materials, from coconut fiber to rattan.

When market day arrives, we head toward the Hive, where you can still see towering buildings far in the distance. Moktar describes them as follies. Constructed, but hardly anyone lived there.

“They found a crocodile on the ninth floor of one of them,” Moktar says.

“They crawl up the pipes,” Ah Kong says.

“I bet the leftmost tower is going to be the next to fall,” Moktar says.

“Not taking the bet. I did once and the gambling party set off a mine that toppled it,” Ah Kong says.

We berth the Mousedeer and use a taxiboat to weave through the boats offering flowers, gadgets, spare parts, rice wine, guardian statues, solar panels, playing cards, water filters, and anything else harvested or salvaged from the buildings, hotels, and bases nearby.

Ah Ma is a fierce bargainer. I’ve seen her reduce vendors to tears and salesbots to reboot in confusion with her sharp tongue.

Ah Kong warns me. “After you’ve heard your grandmother bargain, cover your ears and wash them in the sea when you get back. To think that I still have to listen to this in the afterlife.”

While Ah Ma shops and trades gossip, Moktar and Ah Kong take in some news and other local events. “There’s talk of setting up a school. We should send Ling there once it’s set up,” Ah Kong says.

“If it ever happens,” Ah Ma says.

“You can’t teach her everything,” Ah Kong says.

“Depends on the teachers. If I get a good price on encyclopedias and e-tutors we will be fine.”

Besides bok choy and papaya, Ah Ma procures engine lubricant, tea, batteries, and some gear. Her fish paste and belachan can get you a boat engine, though it’s the kelp bales and the algae oil that net us most of the equipment and bots.

At around 4 p.m., the sharing begins. The greatest moment of joy is when the survivors talk about new finds and discoveries. A once-forgotten variety of luscious rambutan flourishing in an abandoned plantation, horseshoe crabs returning to a debris-covered beach, honey buzzards from half a world away resting on tembusu trees.

When Moktar shares his findings, he states something negative for everything positive. The kelp is growing, but 63 percent died off and he expects more to do so when the monsoon comes. Turtles have returned to lay eggs on the beach, yet he expects a greatly reduced survival rate.

Ah Kong says that is just his way. “When you see the world collapse, you learn not to be optimistic anymore.” The workbot slaps his thighs just like he did.

When the time comes for her sharing, Ah Ma relates the encounter with the trawler. There’s anger, as one would expect from a community when an intruder enters its territory. There are calls to track it down, but we don’t have the resources.

“The time will come,” Ah Ma says. “They will go extinct.” There is loud applause. Other folks relate their own experiences with ghost boats, monsters of the new age.

As the evening light descends, folks relax and food and drink are passed around. People dance and laugh as more games are being played, from skipping rope to congkak to five stones. I hear more stories of the world before, where consequences for actions were ignored.

The end of the evening is marked by the moment of darkness. Lights are switched off and everyone falls into silence. The sounds of the jungle fill the air, and in the distance the pounding of waves. We are in awe. We gaze up at the glorious blazing stars and the Milky Way. We remember the dead and those that have passed. Ah Ma clenches my hand harder than any workbot can.

After the sharing, we spent the night in the house of one of Ah Ma’s friends — a couple who use yam paste to make the most succulent and delicious cakes. Auntie Nina spends her day drawing and coloring the butterflies and wildlife she encounters in the forest, while her husband is an expert on generators and hornbill myths.

At dawn the next day, heavy with kueh and sugarcane water, we haul the gear back to the Mousedeer. Ah Kong grumbles that there’s no liquor, which makes Ah Ma raise an eyebrow. I wonder if she’ll fix its programming so it won’t comment on something it can’t consume.

Nothing much happens over the next few weeks, other than one of the trellises collapsing from the weight of the kelp and the Backrub Beetle blowing a fuse. Ah Ma suggests that Ah Kong’s crystal has sabotaged it.

One evening, I’m training with Iza, another youth of the same age from the village, inspecting the algae and the slowly returning reefs.

We are near some new growths the size of flower buds when an alarm goes off. My watch indicates it is code yellow. Another intruder? Has the autotrawler returned? Iza follows behind me while we swim back to the Mousedeer.

I climb on board the ship and Ah Ma is already donning her suit. Moktar is at the kelong and monitoring with drones. Billy races toward the site.

“Automaton or pirate?” Ah Ma barks, struggling to put a fin on her left foot.

“I don’t see it,” I warn.

“It’s underwater,” Billy messages.

The dolphin sends in images from its camera. It’s a bizarre vehicle that resembles two hubcaps pressed together, with deflated balloons attached around it. It’s at least twice as large as Mousedeer.

“What the heck is that?” Ah Ma says.

One of the balloons detaches and starts to undulate. It wriggles toward the ocean floor and sucks sand up, stirring up a brownish cloud that disrupts the pristine emerald waters. It starts to bulge like a leech taking in blood.

More of the leech bots converge, scooping and sucking up sand. The control vessel spins, spewing out a vermillion-green fluid — chemicals that it uses to process the sand it’s taken in.

“Likely trying to use the sand to reclaim some land somewhere. A tycoon island or defence base,” Ah Ma says. She swears in Cantonese over the communicator. Ah Kong tells her to watch her language.

I imagine the sand stealer bringing back its haul and depositing it on an island that has grown to be the size of a city over the years.

“Bad, bad,” Billy says. “What do now?” He tries to approach one of the leeches but it writhes so violently he backs off.

“I don’t know its weak points. This is new,” Ah Ma says. “But can’t let it take from us.”

Once the leeches are bloated with sand, they squirm back to the mother vessel and place their mouths onto metal orifices resembling barnacle shells. They disgorge their haul, shrinking back into their original slinky, tendril-like forms.

“So much sand in the sea and it has to come here,” Ah Ma says.

“Untraceable and without the protection of a country. Once it’s fed enough, it will go,” Moktar says.

“And then it will unload its base and come back, or send more of its kawan here. Take control of Mousedeer,” Ah Ma says to me. I know that tone of voice.

She prepares some gear while I struggle to keep the Mousedeer steady. She grabs a spear and lowers herself into the lapping waves. The surface of the sea ripples, unaware of the robbery taking place.

I’m too distracted and don’t even notice Ah Ma dropping into the water until I hear a splash. Moktar has a look of worry on his face.

“Your grandmother is bloody cool,” Iza says.

“Always wanting to put herself in danger,” I say. I realize this is something Ah Kong would say, and then realize he is not on board.

On the DugongBot, Ah Ma scooters right at the vessel, a fishing spear under her arm like she’s in a joust.

“What madness is she up to now?” Moktar says.

The vessel senses her approach and lights flare at her. She is too full of rage and too old to care. Realizing it is being accosted, the vessel spins and tries to close its orifices. Some of the leeches abandon their feeding and lurch toward her. She has to dodge to avoid smashing into one of them.

With a burst of speed from the DugongBot, Ah Ma plunges the spear right into an opening before it closes; the metal flaps bite off the shaft of the spear.

There is a snap and then the sound of crackling. Ah Kong’s crystal triggers the weaver bots wrapped around the spear and they swarm out, crawling and wreaking havoc within the vessel like a swarm of locusts.

Ah Ma attempts to ride the Dugong away but the sand stealer, in its death throes, spins wildly. There’s a cloud of vermillion liquid spewing out of the vessel, obscuring everything.

The vessel is out of control. It slams into an outcropping of rock and a kelp trestle. The bloated leeches thrash about, confused.

“Ah Ma,” I say over the communicator. “Ah Ma!”

Billy ducks back into the sand-filled water, trying to look for her.

“Calm down, Billy. You can’t sustain this,” I tell him.

“Must find the lady,” he says. He’s the only one who calls Ah Ma that.

His screen is a cloudy blur. An irritated stingray the size of a blanket rises above the camera, turning the screen dark.

Panicking, I deploy a patrol drone to track her down. The waves are picking up strength, foaming and hungry. I shiver at the thought of losing her.

The drone flies low over the water and spies her floating about a kilometer and a half away. I take control of the DugongBot, which is nearby. With Billy’s help, they get her onto the craft and bring her back to the Mousedeer.

“Fortunately, it is smaller than Moktar. Lighter than a dugong,” the dolphin says, letting out a series of relieved squeaks.

With the workbot, I lift Ah Ma on board. She coughs up water and pulls the broken mask off her face. There’s blood trickling from a wound on her left arm where she’s been pierced by some metal.

We put her on the boat and then back to the kelong. We improvise a stretcher using some net and bamboo poles and move her onto her bed. Iza gets his mother, who’s medically trained. Ah Ma’s face is pale and she seems to have shrunk. I get the gear off her and place antiseptic on the festering wound.

As I remove the Guanyin amulet, I notice that there’s an interface slot. I thought it was just another trinket Ah Ma wore for luck.

“What is this, Ah Ma?” I say.

She sighs, realizing she’s been discovered. “It’s for recording me. When I go, someone needs to teach you Cantonese and remind you to fix the motors, right?”

“You’re ridiculous, Ah Ma. You’re not going anywhere. Besides, who’s going to make kueh from the kelp?”

“I’ll still teach you,” she says.

“You can do it in person.”

“About Ah Kong…” she starts.

“Ah Kong’s crystal. It was not him. Are you going to make a new one? You have the data. And I’m sure you can find a crystal at the market,” I say.

She ponders how to respond.

“It is alright. It was always his hope to perish like a hero.”

“He did it by saving the sea,” Moktar says.

“The sea has no emotion,” Ah Ma says.

“Now who will you argue with?” Billy asks.

“You and Moktar and my headstrong granddaughter,” she replies. The Backrub Beetle covers her feet and she lets out a sigh of relief, chortling.

The evening sun is descending, and the sea is so calm the moon and stars are reflected in it a thousandfold. I knead her muscles and sing a song she taught me a decade ago. She hums it back, sitting up, smiling as she coughs.

Dave Chua is a writer from Malaysia based in Singapore. He is an adjunct lecturer at various educational institutions. He has written a novel, Gone Case (1996), and his short story collection, The Beating and Other Stories, was long-listed for the 2012 Frank O’Connor International Short Story prize. His story “Last Days” won the second prize for ChiZine’s 15th short story contest, and his story “Hantu Hijau” was runner-up for the 2022 Storytel Epigram Horror Prize.

Stefan Große Halbuer is a digital artist from Münster, Germany, who has worked for brands like Adidas, Need for Speed, Samsung, Star Wars, Sony, and Universal Music, as well as for magazines, NGOs, and startups. Recently, he released his first solo book, Lines, a coloring book with a selection of his art from the last years.