This story was originally published by Mother Jones and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

In early 2020, Wilson Truong posted on the Nextdoor social media platform — where users can send messages to a group in their neighborhood — in a Culver City, California, community. Writing as if he were a resident of the Fox Hills neighborhood, Truong warned the group members that their city leaders were considering stronger building codes that would discourage natural gas lines in newly built homes and businesses. In a message with the subject line “Culver City banning gas stoves?” Truong wrote: “First time I heard about it I thought it was bogus, but I received a newsletter from the city about public hearings to discuss it…Will it pass???!!! I used an electric stove but it never cooked as well as a gas stove so I ended up switching back.”

Truong’s post ignited a debate. One neighbor, Chris, defended electric induction stoves. “Easy to clean,” he wrote about the glass stovetop, which uses a magnetic field to heat pans. Another user, Laura, was nearly incoherent in her outrage. “No way,” she wrote, “I am staying with gas. I hope you can too.”

What these commenters didn’t know was that Truong wasn’t their neighbor at all. He was writing in his role as account manager for the public relations firm Imprenta Communications Group. Imprenta’s client was Californians for Balanced Energy Solutions, or C4BES, a front group for SoCalGas, the nation’s largest gas utility, working to fend off state initiatives to limit the future use of gas in buildings. C4BES had tasked Imprenta with exploring how social media platforms, including Nextdoor, could be used to foment community opposition to electrification. Though Imprenta assured me this Nextdoor post was an isolated incident, the C4BES website displays Truong’s comment next to two other anonymous Nextdoor comments as evidence of their advocacy work in action.

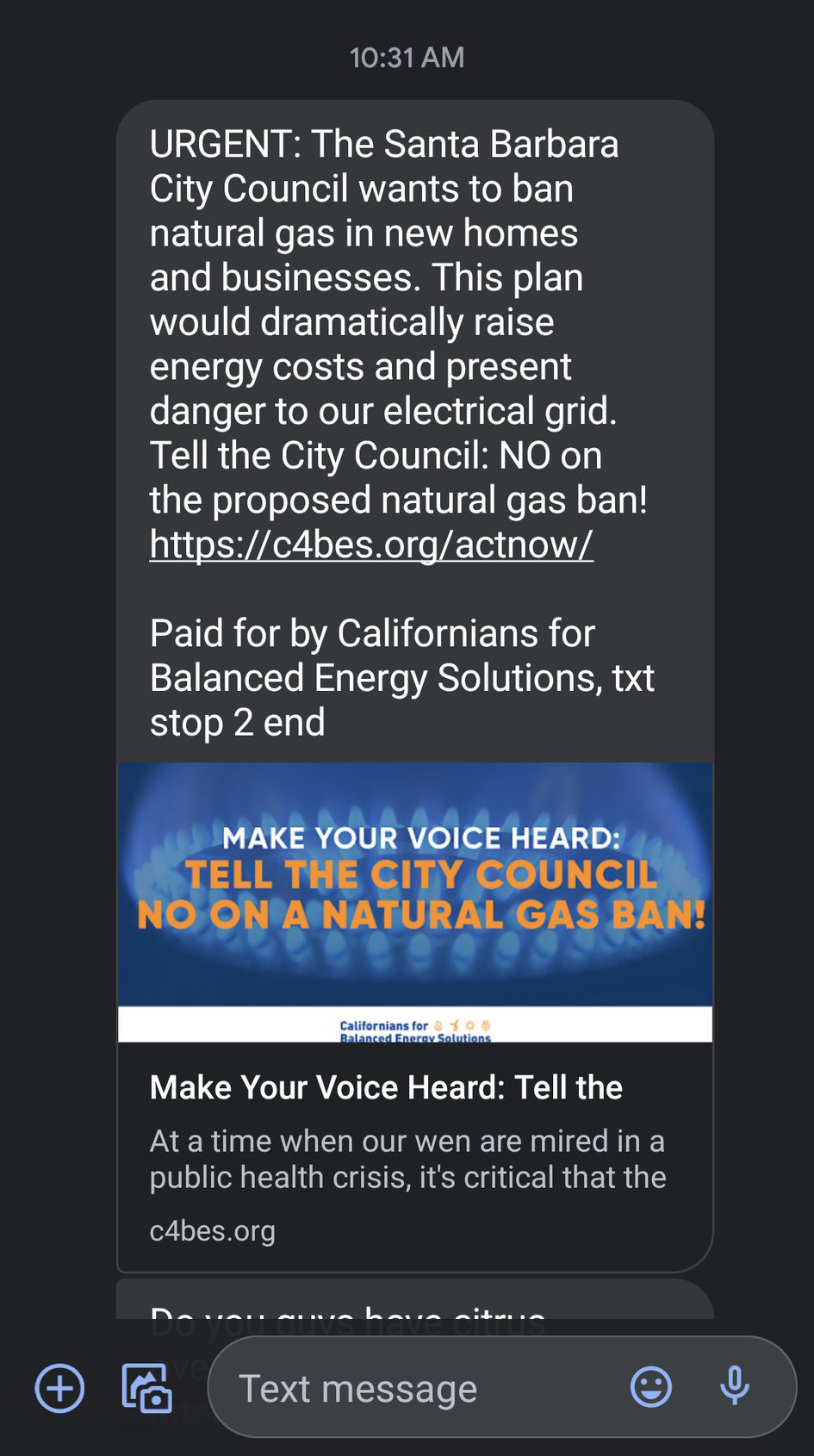

The Nextdoor incident is just one of many examples of the newest front in the gas industry’s war to garner public support for their fuel. As more municipalities have moved to phase gas lines out of new buildings to cut down on methane emissions, gas utilities have gone on the defensive, launching anti-electrification campaigns across the country. To ward off a municipal vote in San Luis Obispo, California, during the pandemic, a union representing gas utility workers threatened to bus in “hundreds” of protesters with “no social distancing in place.” In Santa Barbara, California, residents have received robotexts warning a gas ban would dramatically increase their bills. The Pacific Northwest group Partnership for Energy Progress, funded in part by Washington state’s largest natural gas utility, Puget Sound Energy, has spent at least $1 million opposing heating electrification in Bellingham and Seattle, including $91,000 on bus ads showing a happy family cooking with gas next to the slogan: “Reliable. Affordable. Natural Gas. Here for You.” In Oklahoma, Arizona, Louisiana, and Tennessee, where electrification campaigns have not yet taken off, the industry has worked aggressively with state legislatures to pass laws — up to a dozen are in the works — that would prevent cities from passing cleaner building codes.

The industry group American Gas Association has a website dedicated to promoting cooking with gas.

There’s a good reason for these Herculean efforts: Suddenly, the industry finds itself defending against electrification initiatives nationwide. And the behind-the-scenes lobbying is only one part of its massive anti-electrification crusade. Gas companies have launched an unusually effective stealth campaign of direct-to-consumer marketing to capture the loyalty and imaginations of the public. Surveys have found that most people would just as soon switch their water heaters and furnaces from gas to electric versions. So, gas companies have found a different appliance to focus on: gas stoves. Thanks in large part to gas company advertising, gas stoves — like granite countertops, farm sinks, and stainless-steel refrigerators — have become a coveted kitchen symbol of wealth, discernment, and status, not to mention a selling point for builders and realtors.

Until now, the stove strategy has been remarkably successful. But as electrification initiatives gain momentum, gas companies’ job is getting harder. Now that the industry is getting desperate, parts of its public relations infrastructure have begun cooling on this once-hot client.

Gas connections in American houses are at an all-time high. The share of gas stoves in newly constructed single-family homes climbed from below 30 percent in the 1970s to around 50 percent in 2019 (the data obviously excludes apartment buildings). Today, gas usage for heating, water, and cooking is uneven across the country. Data show 35 percent of Americans use a gas stove, though in some of the most populous cities — particularly those in New York, Illinois, and California — well over 70 percent of the population relies on gas for cooking. Residences also make up the lion’s share of the gas utility profits, making gas appliances a pivotal source for the future of industry growth.

Yet the popularity of gas may soon begin to wane. Americans are waking up to the fact that natural gas is a powerful contributor to climate change and source of air pollution — and that’s not even counting gas pipelines’ tendency to leak and explode. Climate emissions from gas- and oil-powered buildings make up a full 12 percent of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. Just a couple of decades ago, electricity wasn’t the obviously cleaner choice. Now it’s the main strategy for cleaning stubborn sources of pollution. If homes are fully electric, they’re bound to rely increasingly on renewable energy like solar and wind, but every new home that connects to the gas grid today will still be using fossil fuels in 15 years, no matter how much we clean up the electricity sector.

Already at least 42 municipalities across the United States have strengthened building codes to discourage expanding gas hookups in new construction, and the pace is picking up. New York City may soon join that number, while Seattle has settled for a compromise that bans gas appliances in commercial and multifamily homes without technically banning the stove in new construction. In 2021, Washington state will propose bans for gas furnaces and heating after 2030. California regulators have faced pressure to pass the most aggressive standards in the nation to make all newly constructed buildings electric by 2023. President Joe Biden’s campaign promised to implement new appliance and building-efficiency standards. Even with all the gas industry lobbying on the state level, more stringent federal rules could motivate builders to ditch gas hookups for good in new construction.

The dangers of gas stoves go beyond just heating the planet — they can also cause serious health problems. Gas stoves emit a host of dangerous pollutants, including particulate matter, formaldehyde, carbon monoxide, and nitrogen dioxide. Carbon monoxide poisoning is a known killer, which homeowners assume can be prevented with detectors. But new research shows that the standard sensor doesn’t always pick up potentially dangerous carbon monoxide emissions — if a home even has working sensor at all. Nitrogen dioxide, which is not regulated indoors, has been linked to an increased risk of heart attacks, asthma, and other respiratory disease. In May, a literature review by the think tank RMI highlighted EPA research that found homes with gas stoves have anywhere between 50 and 400 percent higher concentrations of nitrogen dioxide than homes without. Children are especially at risk, according to a study by UCLA Fielding School of Public Health commissioned by Sierra Club: Epidemiological research suggests that kids in homes with gas stoves are 42 percent more likely to have asthma than children in homes with electric stoves. Running a stove and oven for just 45 minutes can produce pollution levels that would be illegal outdoors. One 2014 simulation by the Berkeley National Laboratory found that cooking with gas greatly increases carbon monoxide pollution by adding up to 3,000 parts per billion of carbon monoxide into the air after an hour — raising indoor carbon monoxide concentrations up to one-third for the average home.

Shelly Miller, a University of Colorado, Boulder, environmental engineer who has studied indoor air quality for decades, explains that household gas combustion is essentially the same as in a car. “Cooking,” she added, “is the number one way you’re polluting your home. It is causing respiratory and cardiovascular health problems; it can exacerbate flu and asthma and COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease] in children.” Without ventilation, “you’re basically living in this toxic soup.”

Over the last century, the gas industry has worked wonders to convince Americans that cooking with a gas flame is superior to using electric heat. Gas companies have urged us not to think too hard — if at all — about what it means to combust a fossil fuel in our homes.

The gas and electric industries have been in a tug-of-war for dominance in buildings for well over a century. In the early 1900s, gas utilities looked “to other uses for their product; hence the intensive campaign in favor of cooking with gas,” a 1953 newspaper story from the Indiana Terre Haute Tribune reported. The story explains that “gas salesmen knocked on many doors before housewives would turn to gas for cooking fuel.” The industry embraced the term “natural gas,” which gave the impression that its product was cleaner than any other fossil fuel: A 1934 ad bragged, “The discovery of Natural Gas brought to man the greater and most efficient heating fuel which the world has ever known. Justly is it called — nature’s perfect fuel.”

In the 1930s, the industry invented the catchphrase “cooking with gas,” and by the 1950s it was targeting housewives with star-studded commercials of matinee idols scheming how to get their husbands to renovate their kitchens. In a newspaper advertisement by the Pennsylvania People’s Natural Gas Company in 1964, the star Marlene Dietrich vouched, “Every recipe I give is closely related to cooking with gas. If forced, I can cook on an electric stove but it is not a happy union.” (That was around the same time General Electric waged an advertising campaign starring future president Ronald Reagan that showed an all-electric house as the Jetson-like future for a modern home.) In 1988 the industry produced a cringeworthy rap about stoves. “I cook with gas cause the cost is much less/ Than ‘lectricity, do you want to take a guess?” and “I cook with gas cause broiling’s so clean/ The flame consumes the smoke and grease.”

Beginning in the 1990s, the gas industry faced an extra challenge: the mounting evidence that gas in our homes causes serious health problems. Its main strategy has been to exploit the lack of regulation and the uncertainties of science to help lull the public into indifference. Environmentalists say the strategy harks back to how the tobacco industry fought evidence of the dangers of smoking.

The industry claims that there are no documented risks to one’s health from gas stoves, citing the lack of regulation from the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission and the EPA as evidence of why the public shouldn’t be concerned. (To be clear, the EPA has not said gas stoves are safe. Indeed, its 2016 Integrated Science Assessment was the first time the agency linked short-term and long-term exposure to nitrogen dioxide to health problems like asthma. UCLA public health researchers found that indoor nitrogen dioxide emissions from running a stove and oven can rival that from outdoor levels the EPA would consider illegal. Indeed, UCLA data shows California’s biggest source of nitrogen dioxide emissions comes not from power plants, but from gas appliances.)

The industry also claims that proper ventilation mitigates some of the risks of cooking with gas. That’s true, but mostly impractical: Many American families can’t afford to install an exhaust hood, a chimney-like vent that sucks up the emissions and releases them outside, and there’s certainly no regulation requiring it. Instead, most homes just have fans above the stove that recirculate the polluted air inside the home, or nothing at all. Because of dated building codes and an unregulated market, low-income Americans have to put up with gas filling their homes with invisible pollutants in cramped spaces.

In the last few years, the industry has encountered increasing resistance to its claims that natural gas is perfectly safe. Last June, I published a piece that exposed how gas groups representing utilities hired social media influencers to convince millennials and Gen Xers that gas stoves are the superior way to cook. The two main campaigns are the work of the gas trade groups the American Public Gas Association, a collection of public and municipal utilities, and the American Gas Association, which is comprised of privately owned utilities. These groups have hired prominent public relations firms to seek out influencers who emphasize — and whose presence embodies — the cool factor of gas cooking while mentioning none of the risks. In fact, in the posts I reviewed, none of the influencers appeared to have a hood over their stoves, or even to mention ventilation. I knew I had caught the industry’s attention with the story when many of the Instagram posts embedded in the piece were soon deleted, and I started receiving long, mostly unsolicited emails from the industry’s various consultants.

I didn’t know how they had reacted to the negative press until I read a trove of emails obtained through a public records request by the fossil fuel watchdog Climate Investigations Center. According to the emails, representatives from the public relations firm Porter Novelli reached out to their client, the American Public Gas Association, which then asked gas executives at several utilities if its campaign should be paused in light of the backlash. The answer was a definitive no. “They should not stop for even 1 hour,” one utility executive, industry veteran Sue Kristjansson, replied in an email. “And…. if they are saying that we are paying influencers to gush over gas stoves so be it. Of course we are and maybe we should pay them to gush more?”

The emails show gas executives debating their next move: Some thought they should tell the influencers to emphasize guidance around proper ventilation for gas stoves; others, including Kristjansson, wanted to downplay the risks posed by gas stoves altogether. Kristjansson worried that giving even an inch to the critics would be the same as admitting defeat. “If we wait to promote natural gas stoves until we have scientific data that they are not causing any air quality issues we’ll be done,” Kristjansson wrote.

(Since she sent those emails, Kristjansson has moved on to become the president of Berkshire Gas in Massachusetts. When I reached her for comment about her dismissal of the science, the utility sent me a statement on her behalf, repeating familiar claims: “The science around the safe use of natural gas for cooking is clear: there are no documented risks to respiratory health from natural gas stoves from the regulatory and advisory agencies and organizations responsible for protecting residential consumer health and safety.”)

Yet Kristjannson’s hard-liner approach of downplaying the health risks of natural gas seems to be losing favor. Take the example of Kate Arends, the founder of Wit and Delight, a polished lifestyle website for “designing a life well-lived,” and an Instagram account with more than 300,000 followers. Arends’ brand fits perfectly into the affluent female demographic that the gas industry wants to target — and indeed, at least one of Arends’ posts is sponsored by the American Public Gas Association, or APGA.

A week after my story was published, Porter Novelli contacted APGA again, wanting more guidance on how to communicate on “issues related to ventilation,” on behalf of Arends, who wanted to make sure the health and safety information she shared with her followers was accurate. Months passed — by fall I had not seen any sponsored posts from Arends and wondered if she had dropped the sponsorship.

In late October, Arends ran a post sponsored by Natural Gas Genius, the campaign run by APGA: “An Exercise in Candlemaking and the Comforts of a Roaring Fire.” In a 600-word post festooned with photos of her exquisitely decorated and brightly colored home, Arends explained her decision to replace her old wood-burning fireplace with a natural gas model, while extolling the wonders of her gas stove.

Tellingly, Arends’ post includes a note that shows how influencers and the industry have grown savvier on the delicate issue of air quality. “If natural gas is the right choice for your family,” she wrote, “ventilation and air quality are the things to keep top of mind.” It was the first time I had seen an influencer acknowledge the need for ventilation when using a gas appliance. Could it be, I wondered, that these pseudo-celebrities were beginning to have misgivings about their beloved gas stoves?

So far, every city that has tried to pass cleaner building codes has faced an onslaught of gas industry attacks. Sierra Club’s Western Regional Director Evan Gillespie remembers how quickly the gas utility SoCalGas had ramped up its presence just two years ago when one obscure California agency, the South Coast Air Quality District, sought to look at the full emissions impact from gas appliances. Gas groups sent one representative to one meeting, then three to the next, and seven to the third, accounting for a full third of the small meeting’s attendance. Leah Stokes, a political science professor at University of California, Santa Barbara, and the author of a book on utility astroturfing, described the unsettling experience in January of seeing how quickly the SoCalGas-aligned Californians for Balanced Energy Solutions swamped the Santa Barbara council after sending residents texts and emails warning of higher electricity rates and gas stove bans.

But the tables seem to be turning. In November, the powerful environmental regulators at the California Air Resources Board issued an unequivocal statement establishing that gas stoves cause indoor air pollution. The board’s announcement could be a game-changer for cities still on the fence about electrification by recommending “stronger kitchen ventilation standards and electrification of appliances, including stoves, ovens, furnaces, and space and water heaters, in the 2022 code cycle for all new buildings in order to protect public health, improve indoor and outdoor air quality, reduce GHG emissions, and set California on track to achieve carbon neutrality.” The statement marked the first time any major public agency recommended a change of policy to match the science of stoves and indoor air pollution.

Environmentalists liken the move away from gas to the inevitability of coal’s demise in the power sector. They say it’s not a matter of if buildings go electric, but when. If the California Energy Commission declines to issue the all-electric standards for 2022, then it is expected to strengthen ventilation standards, and eventually to ban gas in new construction in 2026. The possibility of a gas ban has sent the industry scrambling: In the event that California’s most populous cities — which account for 8 percent of the nation’s greenhouse gasses for buildings — ban gas hookups in new construction, other states are likely to follow suit.

“If we’re able to get gas bans in new buildings, then these gas companies are losing their growth, they’re losing their new market share, and they’re going to start shrinking,” said Stokes. “With private companies, that sort of downward spiral becomes very problematic, because then investors start to think this isn’t a good company to invest in, or they don’t have a future. The fights that are playing out in California and New York are really bellwethers for the gas industry overall.”

Just as with coal, the pervasive use of natural gas is becoming unjustifiable from both an environmental and a public health perspective. And public relations firms are noticing. In November, Porter Novelli announced that it would drop the American Public Gas Association as a client and would cease its participation in the Natural Gas Genius Campaign. While Porter Novelli declined to comment for this story, the firm’s global chief of staff Maggie Graham explained to the New Yorker, “We have determined our work with the American Public Gas Association is incongruous with our increased focus and priority on addressing climate justice — we will no longer support that work beyond 2020.”

Another recent example of a PR firm parting ways with a gas client happened in Culver City, where Truong made the pro-gas Nextdoor post. When I asked C4BES’s public relations company, Imprenta, about the effort to garner pro-gas stove community support, vice president Joe Zago distanced his company from the incident. He told me he wasn’t aware that Truong had posted the Nextdoor comment himself. Zago said C4BES had tasked Imprenta to find a sympathetic resident of the middle-class Fox Hills neighborhood to post a statement supporting C4BES’s position. Under time pressure, Zago said, “our staff member, on his own behalf, decided to move ahead and post under his own name. He made this post on his own without direction or approval from anyone at Imprenta and without the knowledge of Imprenta or our client.” When I reached out to C4BES for comment, the group’s executive director Jon Switalski responded that his group “supports California’s goals to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, however an ideological solution that places increased burdens on working families is not the only path to decarbonization.” Imprenta told me that its contract with C4BES expired in February 2020. (The groups are also the subject of a California consumer advocacy investigation about improperly using ratepayers’ dollars for other campaigns against electrification.)

Environmentalists point to the examples of PR firms dropping their gas-industry clients as evidence of a shift in public sentiment on gas. “I think people’s perception of what it means to have a gas stove changes pretty quickly,” Gillespie said. Consumers are beginning to realize, “I’m burning fossil fuels with an open flame in my house, and it’s contributing to asthma my kid has; it’s harming my mom, my dad, and my grandparents.”

The gas industry has spent a century convincing Americans to fall in love with gas stoves, and there’s no telling how it will recover if that relationship sours. As the public begins to fully understand the environmental and health risks of what used to be their favorite appliance, Gillespie predicts, “what was long seen as this great strength of the industry is actually their greatest weakness.”