While the U.S. Gulf Coast is poised to set a new record for the highest number of named storms in a single calendar year, the Pacific Ocean is dealing with its own superlative weather worries.

Typhoon Goni slammed into the Philippines on Sunday with peak winds of nearly 200 mph, killing at least 20 people and displacing more than 350,000. It was Earth’s most powerful storm of 2020, and although it weakened somewhat before making landfall, Goni was still the strongest typhoon to hit the country since 2013, when Super Typhoon Haiyan took the lives of more than 6,000 people.

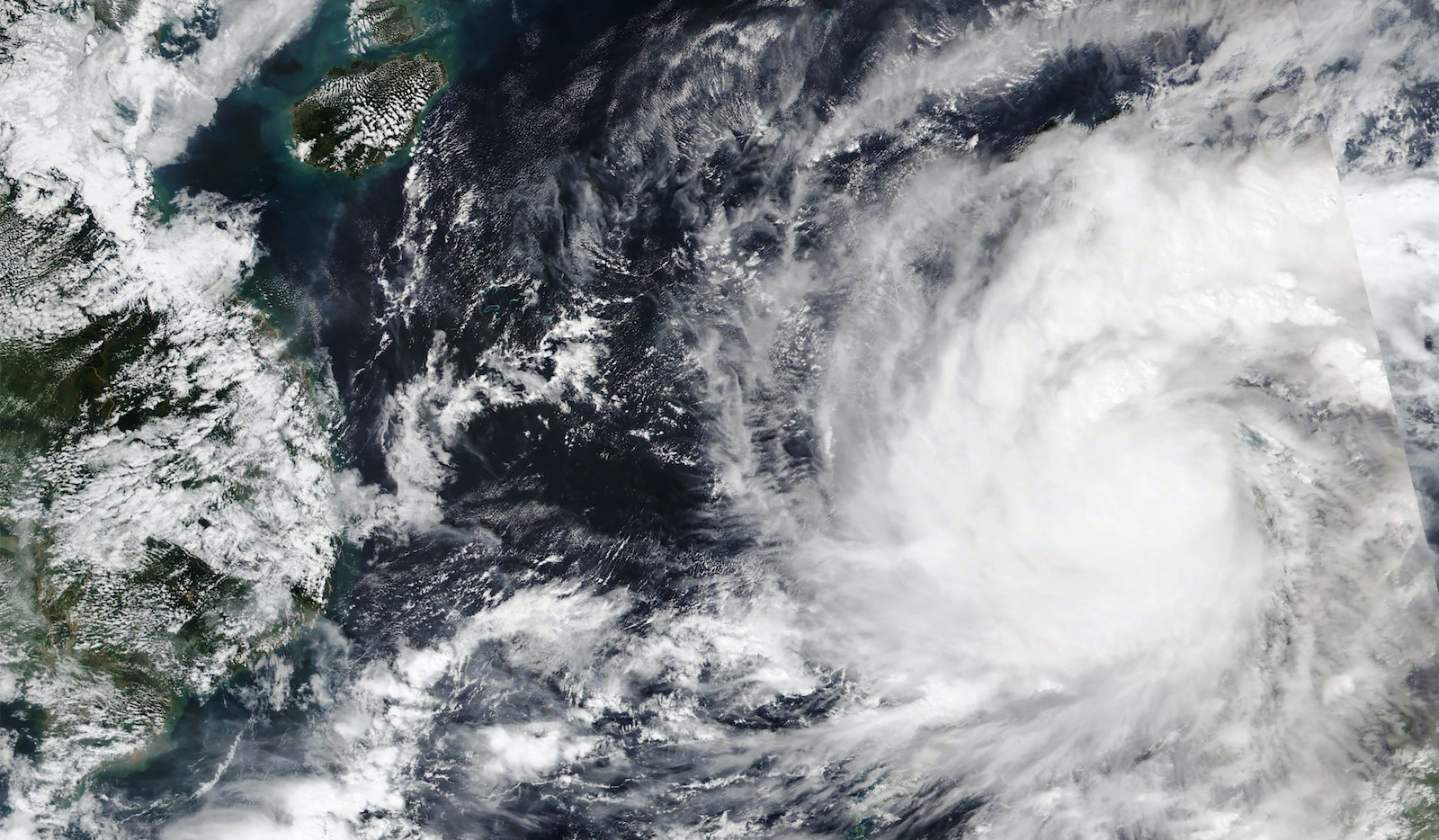

Typhoon Goni logged peak wind speeds near 200 mph. NASA via AP

Government officials and aid organizations were still surveying Goni’s aftermath on Monday, but some sources estimated that tens of thousands of homes had been destroyed. In one city on the island of Catanduanes, where the storm first hit, as much as 90 percent of buildings sustained some form of damage, according to initial reports from the Red Cross. Provincial Governor Joseph Cua said much of the damage was due to the island’s 5-meter (16.4 feet) storm surge.

“This is the human face of climate change,” tweeted Naomi Oreskes, a history of science professor at Harvard.

Global warming may have contributed to Goni’s rapid intensification, as wind speeds nearly doubled late last week when the storm passed over an area of warmer-than-usual ocean water in the Pacific (around 87 degrees F — up to 3 degrees F above average). Virtually overnight, Goni escalated into the equivalent of a Category 5 hurricane. Thanks to these anomalous temperatures — which are a product of climate change — climate scientists say similar superstorms could happen eight times more often by the end of the century.

Usually, high hurricane activity in the Atlantic means you can expect less activity in the Pacific. And until Goni, the western Pacific was actually experiencing a relatively tranquil typhoon season, judging by the number of named storms and their cumulative power. Storms in the region had only generated 40 percent of the power typically observed by mid-October. And only one other storm, Haishen, garnered the 150 mph wind speeds necessary to be classified as a super typhoon.

However, low activity in the region is not evidence against climate change. Instead, scientists say it illustrates the oceanic and atmospheric relationship between the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. As the Washington Post put it, “When one ocean basin booms, the other remains quiet.” And since 2020 is a La Niña year, weather patterns including warmer waters in the Atlantic have enabled more hurricanes to form there, while keeping Pacific storms mostly at bay.

But, as Goni proved, there are exceptions to the rule.

Charism Sayat / AFP via Getty Images

Goni only grazed the Philippine capital of Manila, largely sparing the megacity’s nearly 14 million people. But on the country’s main island of Luzon, the storm caused more than 50,000 homes to lose their power, and economic damages across the country look steep. According to government documents and officials, Goni caused up to $35 million in damages to the nation’s crops and another $115 million to the country’s infrastructure.

“This typhoon has smashed into people’s lives and livelihoods on top of the relentless physical, emotional and economic toll of COVID-19,” said the Philippines’ Red Cross chair Richard Gordon in a statement.

The country is now bracing for another storm, Atsani, which is expected to make landfall late this week. President Rodrigo Duterte said in a cabinet meeting that he did not expect it would be as powerful as Goni, but that it could still cause damage.

Many environmental advocates expressed solidarity with the Philippines, noting that climate-related disasters like hurricanes and typhoons disproportionately harm populations outside of the world’s most polluting countries. The Philippines contains approximately 1.4 percent of the world’s population, but was responsible for just 0.2 percent of global CO2 emissions in 2017.

“Yesterday it was the Philippines and #Goni; tomorrow it is Nicaragua and #HurricaneEta,” tweeted climate activist Bill McKibben, referring to the Category 4 storm gaining strength off the eastern coast of Central America. “The less you did to change the climate, the harder you get hit.”