The Paris Agreement shouldn’t be working.

In many ways, the landmark climate accord, agreed to at a U.N. summit in 2015, is a weak treaty. Despite the fanfare that accompanied its signing, the agreement has no binding limits on emissions, relies on countries to set their own goals for slashing pollution, and rests on an assumption that they can be shamed into living up to their promises. It’s not even a real treaty: To get the U.S. on board, the architects of the accord crafted it as an “executive agreement” — no Congressional approval needed.

And yet, somehow, the Paris Agreement is working. To a point.

The most recent U.N. climate conference, which wrapped last weekend in Glasgow, Scotland, showed signs of progress that would have seemed unthinkable only a few years ago. Under the Paris Agreement, nations have to submit pledges (or promises, or wishful thinking, depending on who you ask) for how much they will reduce emissions every five years. That’s the core of the agreement: Voluntary pledges enacted and reviewed in a soup of international peer pressure that, ideally, will push countries to steadily do more and more. The goal is to use this system of “pledge and review” to limit global warming to “well below” 2 degrees Celsius — or, ideally, 1.5 degrees Celsius.

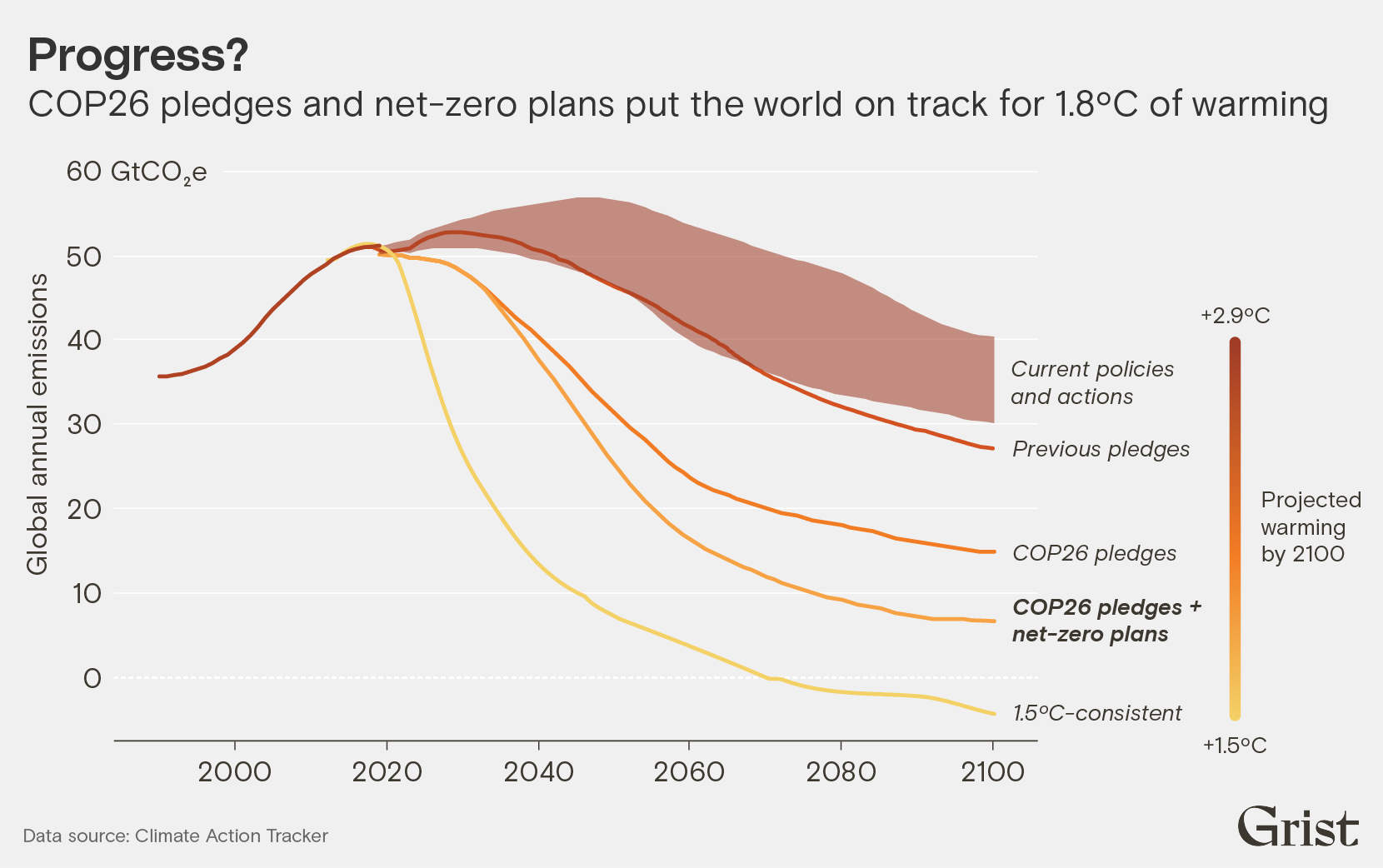

As of 2018, however, all 192 countries’ pledges added together — assuming they are actually met — would have only reduced warming to 3 degrees Celsius by 2100. At that temperature, almost all coral reefs would likely die, and a quarter of all species could vanish. Not to mention the disappearing coastlines and searing heat waves.

But during the Glasgow conference, known as COP26, a strange thing happened. Countries began making bigger promises, both in the short-term (by 2030) and in the long-term (by the end of the century). India, the world’s fourth-largest emitter of greenhouse gases, vowed to zero out its emissions by 2070; 141 nations agreed to end deforestation; and the U.S., along with 129 other countries, promised to cut emissions of methane, a highly potent greenhouse gas. By the end of the conference, the International Energy Agency announced that if all countries’ current promises are kept, the world will warm 1.8 degrees Celsius — seemingly on track to meet the Paris Agreement’s goal of keeping emissions “well below” 2 degrees Celsius.

“We came to Glasgow on a path to disaster (2.7°C),” Johan Rockström, an environmental scientist and the director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany, wrote on Twitter. “We leave Glasgow on a path to danger (just below 2°C).”

How could this be? Paradoxically, the weaknesses of the Paris Agreement — its feeble enforcement measures and non-binding nature — are also its strengths. “Formal international law is overrated, frankly,” said David Victor, a professor of public policy at the University of California, San Diego. The genius of Paris, according to Victor, is its flexibility: It lets countries choose how ambitious they want to be.

That might sound strange. For decades many economists and policymakers believed that the only way to take on climate change was through some kind of collective, binding agreement — one that would force countries to take action and punish those that don’t. That was the approach tried in the Paris Agreement’s predecessor, the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, which bound countries to emission reductions, with financial penalties if they didn’t comply. It was a textbook solution to the climate crisis.

But the Kyoto Protocol soon fell apart: The U.S. failed to ratify the treaty, and Canada, unable to meet its commitments, dropped out. Attempts to revive it at the U.N. summit in Copenhagen in 2009 failed miserably.

The problem with binding commitments, according to Victor, is that they tend to be unambitious. If a nation knows that it will face stiff penalties for not following through, it won’t want to promise as much. Paris ducks that problem. “What you want to do is liberate countries to make ambitious pledges,” Victor said. “Get them to do as much as possible and put as much on the table as possible.”

There are, of course, huge caveats. To meet the goal of keeping warming well below 2 degrees Celsius, countries actually have to follow through on those promises — something most have not been known to do. Many countries are not on track to hit their first round of pledges under the Paris Agreement, and those that are, including the U.S., have been helped along by emissions drops from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Some researchers have tried to estimate whether this kind of “pledge and review” system will work to create actual action, and the results are … not particularly encouraging. One experiment, conducted by researchers at Columbia University and the University of Kassel in Germany, involved a game in which players acted as individual nations under the Paris Agreement. The “name and shame” system of emissions cuts, they found, was good at getting players to pledge more, but not as good at getting them to actually follow through.

“The framework seems to change what players say, and not what they do,” said Scott Barrett, a professor of economics at Columbia University and one of the authors on the study.

It’s too early to tell whether that will be the case for Paris. Despite rhetoric from climate activists (at COP26, Swedish activist Greta Thunberg complained that all the negotiations added up to nothing but “blah blah blah”) who expect these conferences to deliver clear results, U.N. climate summits aren’t supposed to make new policy. They are supposed to rustle up big, ambitious pledges and provide the impetus — through public pressure and diplomatic scolding — for countries to go home and start the hard work of slashing greenhouse gas emissions. By themselves, summits won’t deliver emissions cuts. That’s for individual countries — and individual industries — to do.

In a way, Glasgow’s result may mark the beginning of the end of the “pledge” stage of climate negotiations. As countries’ promises align more closely with the Paris Agreement’s goals, attention will shift to follow-through — and there, U.N. summits may not be as useful. Victor expects to see more bilateral agreements and agreements within industries, some of which were already on display at COP26. Over 30 countries and several major automakers agreed to stop building gas-guzzling cars, and the U.S. and China promised to work more closely together to cut emissions over the next 10 years.

There will still be tussles at future climate summits — especially fights over money, as poor countries seek promised funds to help them switch over to clean energy and put pressure on rich countries to compensate them for climate-related damages. But as an ambition-raising process, the Paris Agreement, for all its faults, is working. Now countries just have to deliver.