Ever since workers strung the wires of the first electrical grid in 1882, buildings have been gobbling up energy. But what if that relationship were upended so that buildings fitted with solar panels produced more electricity than they consumed?

Turns out, that’s already well underway: The number of buildings constructed so ingeniously that they sometimes feed energy to the grid has nearly doubled in the last two years.

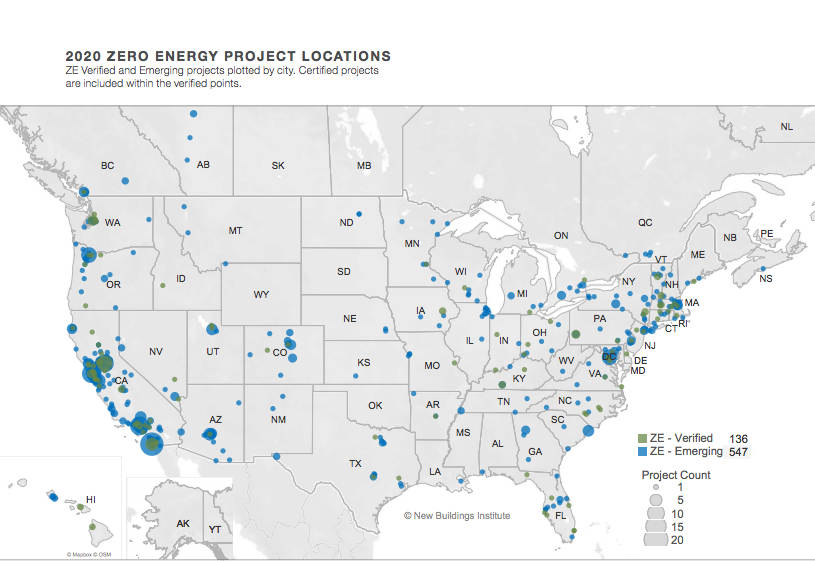

The nonprofit New Buildings Institute keeps a list of these “zero energy” offices, schools, and libraries. In 2018, there were 67 large buildings around the United States and Canada that got the stamp of approval for meeting this mark over a full year. Since then, 136 have hit that target. And there are more than 500 other buildings around the U.S. on track to join them. They’re popping up all over the continent, like a strange form of measles that makes countries healthier.

Map courtesy of New Buildings Institute.

What’s driving this trend? Buildings last a long time, so their owners try to plan for the future. They can see that the number of extreme weather events is on the rise and that the cost of powering a building with fossil fuels could rise as governments get around to tackling climate change.

“It’s a form of future-proofing, a way building owners can make sure they are on the right side of these various trends,” said Alexi Miller, an associate director of the New Buildings Institute

While all these green buildings won’t solve the climate crisis, they can show the way.

“It demonstrates the power of the possible,” Miller said. “It shows you can get all the way to zero energy in every climate zone and building type.”

Think of them as testing grounds for new techniques and technologies which could soon wind up in your grocery store, City Hall, and office building (if you ever see that again). Buildings eat around 75 percent of all electricity in the United States. Reduce that electricity demand and it makes it easier to close down power plants running on gas and coal. And buildings suck up even more electricity — 80 percent — when electricity demand is highest, often just after sunset, a problem for getting rids to rely on solar power. But if buildings are supplying their own energy they can smooth out these peaks — and push them to other parts of the day.

Technologies that seem fanciful at first can wind up as the norm. Take airbags. In the late 1970s, they were only found in luxury cars — a high-end gadget for the rich. But they grew cheaper and more efficient as factories began producing them to meet rising demand. Then U.S. regulators told automakers to put them in all new cars, starting in 1998.

The same combination of interest from buyers, market forces, and government regulation, might put many features of these green buildings into the homes and offices of the future. Here are five trends emerging from super-high efficiency buildings that could one day become as ubiquitous as airbags.

1. Designing for disaster

Home batteries, to provide power backup, and move solar energy into the night, are neat.

When a polar vortex drew the mercury down to -24 degrees Fahrenheit in Chicago, people turned up their furnaces and huddled close to their radiators. But not in the Ellis Passivehaus, a house built to exacting efficiency standards. The heating system barely registered the extreme weather as it kept the house at a comfortable 71 degrees.

In a world of storms that tear down power lines and fires that fill the outside air with smoke, a hyper-efficient building can come in handy.

What is efficient is resilient. A home that’s sealed up tight to prevent heat from leaking out will also prevent smoke from leaking in. Windows designed to allow the sun to do most lighting work will be easier to navigate during power outages. Thick insulation meant to keep energy bills down could be a lifesaver during record heat waves.

“These buildings with solar panels and batteries, that have natural light, and passive heating and cooling — all these things they need to be zero energy also make them a lot less vulnerable to extreme events,” Miller said.

2. An airtight jacket

Fairwood Commons, completed in 2018. There is a lot of insulation under that ordinary-looking exterior. Photo courtesy of Woda Cooper Companies.

When designers started planning the Fairwood Commons, an affordable housing project for seniors in Columbus, Ohio, they decided to seal the entire building and pack the walls with an extra thick layer of insulation. It cost more money initially, but it meant the residents needed almost no heating and cooling, keeping the energy bills down.

The new well-insulated structures like this one going up around the country are built like thermoses — able to stay warm or cool no matter the weather outside. They require only an occasional nudge from their heating and cooling systems to stay comfortable year round.

Miller is the first to admit that insulation and sealing doesn’t have the sex appeal of a fancy new gadget. “It’s not terribly complicated right? It’s pretty easy to tape over the seams to stop airflow,” he said.

But it works so well that these practices are spreading fast. Look closely at new construction, and you’ll likely notice more new buildings clad in a layer of insulation.

3. Extracting heat from winter air

The amazing heat pump. Photo courtesy of Northwest Energy Efficiency Alliance

The heat pump has been around since the 1850s, but they’ve only gotten good in the last few years.

The device that keeps a refrigerator cold is a small version of a heat pump — it captures heat inside the fridge and releases it outside. Reverse it, and it would do just the opposite, heating the refrigerator and cooling your house. Put a bigger version in a building and you can run it in either direction, providing heating or cooling for your whole house.

And people have been using heat pumps in place of gas furnaces for over a century. The house I lived in as a kid had one of those old heat pumps, but after a couple $400 electricity bills my parents switched to a wood stove.

Heat pumps were expensive in the old days, because they failed in low temperatures and reverted to wildly inefficient resistance heating, Miller said. That’s basically like heating a house with an oversized toaster: It sucks up a lot of electricity to produce a little heat. Thanks to a series of breakthroughs, the new models work fine in frigid winters.

One of them newfangled heat pump water heaters. Photo courtesy of Northwest Energy Efficiency Alliance

Miller is even more enthusiastic about heat-pump water heaters. “They’ve gotten a whole lot better, and much less expensive,” he said. “They are reliable and efficient.”

So efficient that they tend to come with a variety of government rebates. Add it all up and they’re often the most affordable option: Miller installed one for his mother-in-law recently, which ended up costing about $225. Conventional builders just don’t know to look for them yet, he said.

4. Working with the sun

The new Sonoma Clean Power headquarters is built to use only the cleanest electricity. Courtesy of EHDD Architecture

In 2017, when Sonoma Clean Power bought an old office building in Santa Rosa, California, to be its new headquarters, they decided to remodel it to minimize carbon emissions. In California, electricity is dirtiest on summer afternoons when one gas plant after another fires up to provide power to everyone who runs their air conditioners. So architects paid special attention to the west-facing windows that let in the afternoon heat.

“You can figure out the angle of the sun on August afternoons and design shades that block it then, but allow the sun in when it is at a lower angle in the sky, in the winter,” Miller said.

The designers also realized they could avoid more of that dirty electricity if they pointed the building’s solar panels to the west, to capture the setting sun, rather than pointing them to the south. They also included batteries to store some of that solar energy to use after the sun sets.

Including these features in the construction, which started in June, will give the company’s new headquarters the ability to time its energy use, “depending not only on price, but also on the carbon content of the electricity on the grid,” said Cordel Stillman, director of programs for Sonoma Clean Power.

Tweaks like this can reduce the mismatch between the time when solar panels pump out electricity — in the middle of the day — and when people consume the most electricity — in the evenings.

“It’s going to be really hard to actually get to the 100-percent clean energy goals unless buildings are supporting the grid,” Miller said.

5. Low-carbon materials

At the cutting edge, climate-conscious builders are starting to trace the life-cycle of the products they use in an effort to curb carbon emissions. But it can complicate things. A lot of the best sealants and insulating materials are petroleum products. A lot of the exterior insulation increasingly used to wrap buildings (see above) is styrofoam, or similar materials with truly astounding carbon footprints. It does little good to save a few tons of carbon through building efficiency if you release megatons of carbon making the materials.

As builders do their research they are hopeful: Done right, each new home could store more carbon than it gives off. By substituting sustainably harvested timber for concrete and steel, for instance, buildings could shift from being part of the problem to being part of the solution.