A stocky blue 980-foot-long tanker named Christophe de Margerie sailed from Russia’s far-north Yamal Peninsula to the Bering Strait near Alaska in May, two months before such ships usually pass through a major Arctic sea route. The vessel carried and ran on liquefied natural gas, accompanied by the icebreaker Yamal on the 12-day journey. Record-low ice levels along the route allowed its Russian owner, Sovcomflot, to ship the fossil fuel to China, completing the earliest voyage of its kind yet.

If the milestone signals big opportunity for oil and gas producers, it also embodies two troubling trends for the rest of the planet.

More large ships Like the Christophe de Margerie are running on liquefied natural gas, or LNG. That switch is resulting in higher emissions of methane, a potent greenhouse gas, according to a new report by international shipping experts. The vessel’s voyage also comes as Arctic ship traffic is rising, a development made increasingly possible by above-average temperatures and disappearing sea ice—particularly along the Christophe de Margerie’s Northern Sea Route. A recent study raised the possibility that Arctic summers could be completely free of sea ice by 2035.

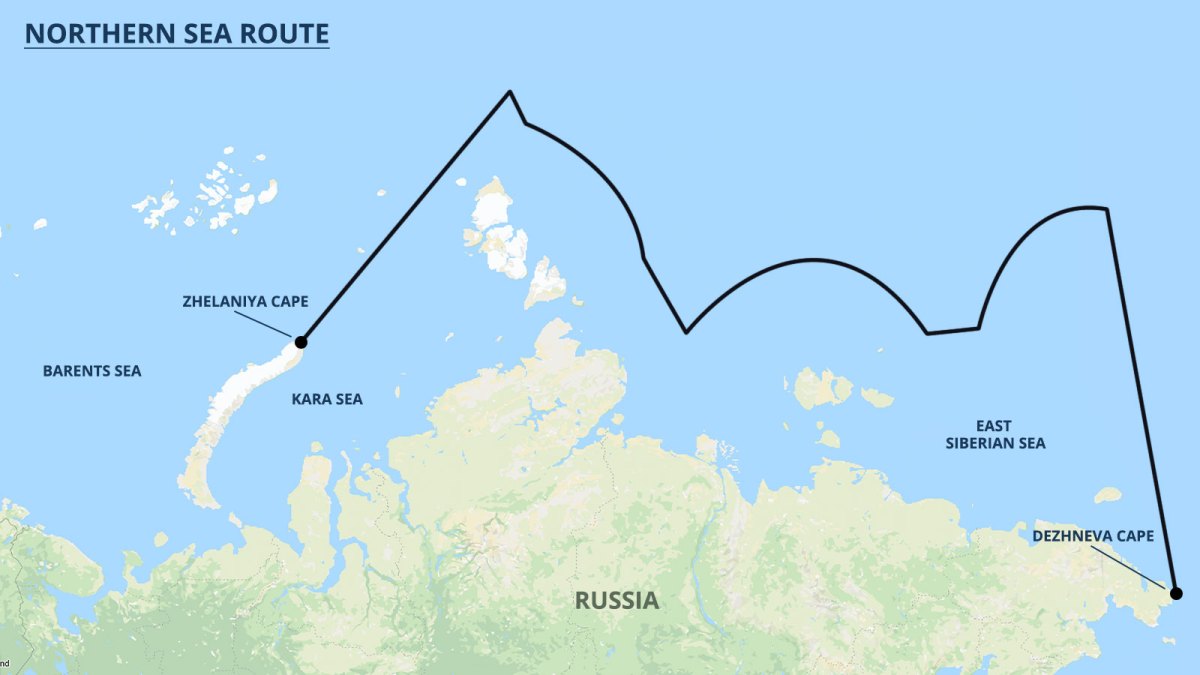

“Because the climate is warming, it’s opening up more and more,” Mark Serreze, director of the National Snow and Ice Data Center, said of the 3,000-mile-long passage.

Ice in the Laptev and East Siberian Seas began melting earlier than usual this year, fueled by a Siberian heat wave that also triggered massive wildfires. The Christophe de Margerie still had to forge through treacherous ice, but by mid-July, the route appeared to be ice-free, the earliest that’s been known to happen.

Sea ice conditions are still “highly variable” from year to year and depend on the seasonal wind and weather patterns, Serreze said. But the route’s early opening “is part of a trend,” he added. “Overall, we’re losing ice cover over the Arctic Ocean. We are decidedly downward.”

No group is better poised to capitalize on the warming Arctic than Russia’s oil and gas giants. Gazprom and Rosneft have recently expanded offshore Arctic drilling, while Novatek and other partners built a massive LNG production facility in Sabetta, which switched on in late 2017. Ships have since moved tens of millions of tons of the gas to European markets and, taking the Northern Sea Route, to major ports in Asia.

Many of those LNG tankers also burn the fuel along the way, which shipping companies tout as a good development for the environment. SCF Group, the Russian shipping company that owns Christophe de Margerie, recently boasted that “the vessel that began this new era in Arctic shipping both carries LNG, the cleanest fuel currently available, and uses LNG fuel herself, which drastically reduces the vessel’s impact on the environment.”

As countries and global regulators work to curb pollution from ships, more companies are using LNG not only for specialized Arctic tankers, but also for passenger cruise liners and behemoth container ships. When burned, LNG produces little nitrogen oxide and virtually no sulfur dioxide, two harmful pollutants linked to asthma, heart failure, and other health problems. It’s also estimated to reduce a ship’s onboard carbon dioxide emissions by about 20 percent, compared to conventional marine fuels.

At least 750 cargo ships, tankers, tugboats, ferries, and other vessels today can run on LNG, or double the amount available in 2012.

Yet burning LNG means they’re emitting more of the supercharged greenhouse gas, methane. The gas traps much more heat in the atmosphere than carbon dioxide, further accelerating climate change. Environmental groups have raised concerns that switching to LNG will ultimately hinder—not help—the shipping industry’s broader effort to reduce emissions.

As more vessels have switched to using LNG, the industry’s methane emissions rose by 150 percent from 2012 to 2018, according to a recent study commissioned by the International Maritime Organization, the U.N. body that regulates shippers. That’s even though vessels burned roughly 28 percent more LNG over the six-year stretch.

The problem is that many marine engines “are quite leaky,” said Bryan Comer, a senior marine researcher at the International Council on Clean Transportation, who contributed to the IMO study. “High amounts of methane are escaping out of the (ship’s) chimney unburned,” he said. “It’s just being emitted straight into the atmosphere.”

Researchers tallied emissions of another powerful pollutant, one that hadn’t been counted in previous IMO reports: “Black carbon,” or dark soot-colored particles, which rose by 12 percent over the study period. Most of those emissions came from ships burning heavy oil-based fuels and not LNG, which produces barely any black carbon.

That emissions hike is especially pronounced in the Arctic, a region that’s uniquely sensitive to black carbon. When dark particles land on the ice, it causes the white sheets to absorb more of the sun’s energy, which speeds up melting. In the Arctic alone, black carbon emissions shot up 85 percent from 2015 to 2019, Comer’s team found in a separate study. Fishing vessels and oil tankers — many flying Russian flags — are the main culprits.

The IMO doesn’t yet regulate methane emissions or black carbon from ships, just carbon dioxide. The U.N. body wants to reduce the industry’s total greenhouse gas emissions by at least half of 2008 levels by 2050. But it’s still figuring out how to give that goal real teeth.

Both environmentalists and trade organizations are pushing to include methane in the U.N. agency’s set of mandatory standards for newly built ships. Outside groups are also calling to remove loopholes in a ban on the use of heavy fuel oil in Arctic waters, in order to reduce black carbon. A major IMO meeting to review environmental regulations in March was postponed as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, and is now scheduled virtually for November.

In the meantime, hundreds of Arctic vessels will continue traversing the Northern Sea Route. The passage is likely to remain open for the next two to three months, ice chart data show, providing ample access for Russia’s gas producers. Christophe de Margerie, the big blue tanker, was back in Sabretta earlier this month, refilling its huge tanks with LNG.