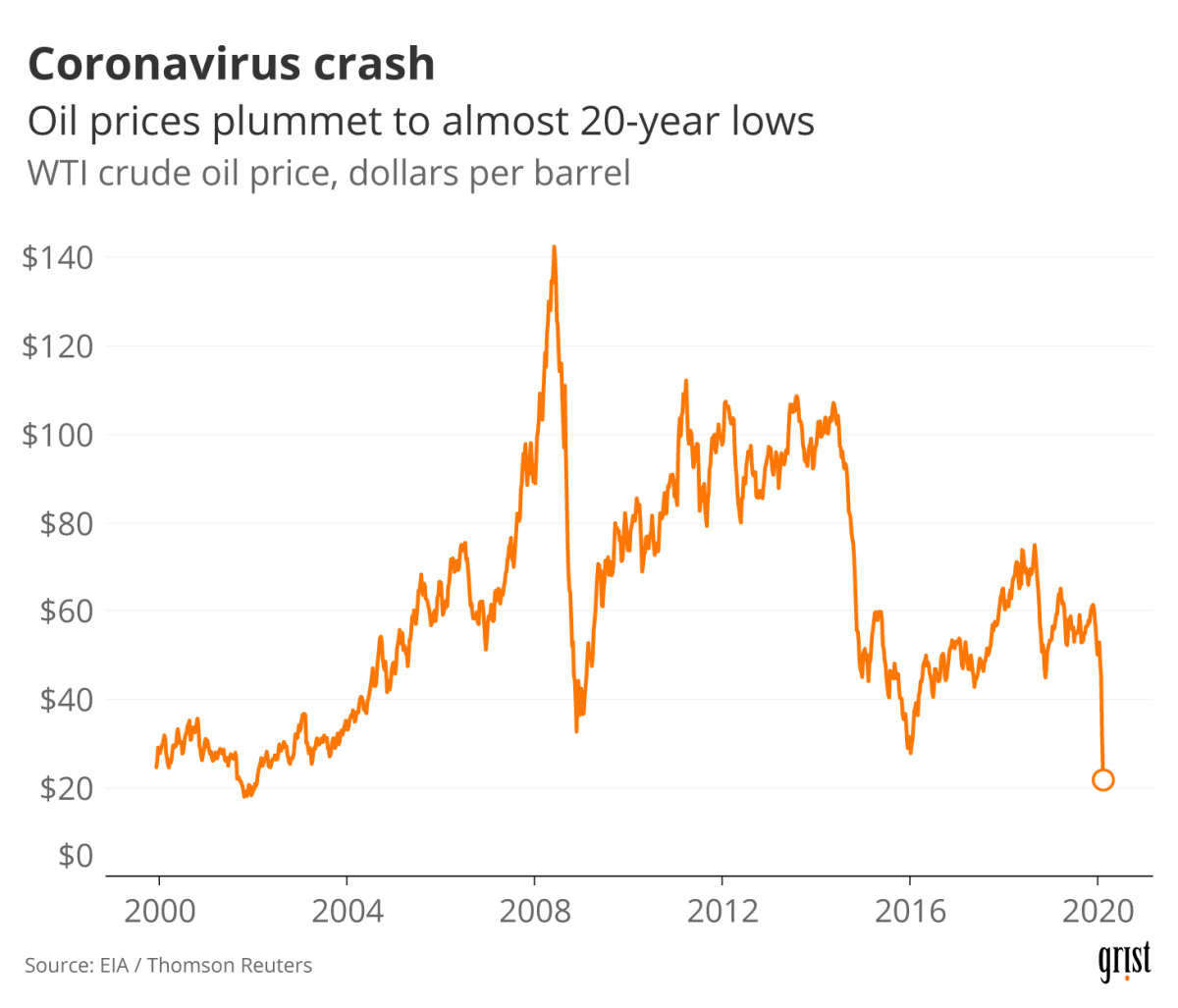

As oil prices cratered to an 18-year low last week, news leaked that oil and gas producers were asking Texas regulators to mandate a statewide cut in production — a drastic measure that hasn’t been attempted since the 1970s.

On Friday, the Wall Street Journal first reported that the Texas Railroad Commission (which, despite its peculiar name, regulates the state’s oil and gas industry) was contemplating instituting production cuts. Other news outlets later confirmed that the agency is studying whether capping the amount of oil produced in the state is practical, and whether it could even do so under existing laws and regulations.

If implemented, the measure could have serious economic ramifications for Texas and the rest of the U.S. But without the cooperation of other states, the federal government, and other oil-rich countries, energy experts say that slashing production in Texas alone is unlikely to provide serious relief to domestic oil and gas companies teetering on the edge of financial ruin.

The fact that such an extreme step is being considered at all is an indication of the dire predicament facing oil and gas producers. Banks have slashed oil price outlooks and now expect that prices will average between $25 and $35 per barrel for most of the year. That’s at least a third lower than projections for 2020 from just a few months ago — projections that were already pretty low to begin with. Market analysts estimate that operators in the Permian Basin in West Texas need around $47 per barrel to break even. Proration, a regulatory term for production limits, could help companies shore up prices by making a dent in the industry’s overabundant supply.

Clayton Aldern / Grist

But a number of regulatory and practical hurdles remain in the way of implementing caps on oil production. For one, states last ordered companies to cut production almost half a century ago. As a result, regulatory agencies lack the institutional knowledge needed to recreate practical proration programs that can work in an energy landscape that is very different from that of the 1970s. In some cases, states may not be able to devise proration programs without first making regulatory changes, a process too time-consuming to get relief to producers by the time they need it. In New Mexico, for instance, current rules do not allow caps on a subset of wells, and instituting proration will require a rule change.

Apart from Texas, no other state seems to want to take on those challenges so far. Grist contacted representatives from Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, North Dakota, and New Mexico. Spokespeople for regulatory agencies in New Mexico and North Dakota told Grist that, while they’re aware of the discussion in Texas, they are not currently considering proration.

Earlier this month, the Oklahoma Corporation Commission, which oversees the state’s oil and gas production, lowered the production cap for natural gas at a select group of wells. Matt Skinner, a spokesperson for the agency, said the move was largely symbolic and is not expected to drive down production significantly. The agency has no current plans to consider larger cuts in part because oil and gas companies are divided over such measures, he said.

States regularly set limits on oil and gas production from the 1930s to 1970s. After Dad Joiner, a rogue Texas wildcatter, discovered highly productive oil wells in East Texas in 1930, cheap oil flooded the market and the price dropped from about $1 per barrel to less than 5 cents. As a result, states began passing laws in the late 1920s and early 1930s to regulate production. Congress also created the Interstate Oil and Gas Compact Commission to help states coordinate production, and the federal government announced tariffs on oil imports. Both steps were necessary to prevent states or other countries from undercutting individual production limits by flooding the market with cheap oil.

Since Texas was home to the largest oilfield in the world at the time, the Texas Railroad Commission led the charge on capping production. The Commission announced statewide limits, with individual limits per oilfield and even per well. These proration regulations would later become a model for the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, a cartel of 14 nations including Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and Venezuela.

Many states still have the proration rules introduced during the 1930s oil glut on the books, but they haven’t used them since the 1970s, when production in the U.S. peaked and prices began a decade-long rise.

“There’s no reason why [proration] couldn’t be reinstated,” said Owen Anderson, an energy law professor at the University of Texas in Austin. “Texas and Oklahoma still go through the motions of [proration].”

Texas publishes a proration schedule every month for every operator in the state, and Oklahoma’s oil and gas agency reviews its complex set of rules that govern production caps routinely at public meetings. But both states generally either set higher caps than producers can meet, or they simply suspend their rules to encourage further exploration.

At least one of the Texas Railroad Commission’s three elected members appears open to the idea. In an op-ed for Bloomberg, commissioner Ryan Sitton raised the possibility of production cuts but called on President Trump and the federal government to work with other oil-producing countries to stabilize markets. “While Texas controls its destiny, it doesn’t control that of others,” he wrote.

Those in the oil and gas industry also seem divided on whether quotas will be effective in bolstering prices. Todd Staples, president of the Texas Oil & Gas Association (TXOGA), said in a statement earlier this week that proration is “not a remedy TXOGA members are seeking.” Staples said that, if Texas oil and gas operators alone cut back production, that void will likely be filled by other operators outside the state. “TXOGA members remain committed to free market solutions,” he said.

Anderson, the law professor, said that the proration system that existed during the last century worked because there was cooperation with other countries: “In the 1930s, the so-called seven sisters — the seven large oil companies — worked to make sure that production from other countries didn’t overwhelm the system.”

Anderson said that if the Trump administration intervened by either slapping tariffs on large oil producers such as Saudi Arabia and Russia, or worked with them to voluntarily reduce production, it could help stabilize prices. But those steps seem unlikely anytime soon, given that the White House will be busy battling to contain the spread of COVID-19 for at least the next few months.