The U.S. energy transition is well underway. Electricity from solar and wind is increasingly competitive with natural gas power, and the grid is hemorrhaging coal plants that no longer make economic sense. But without any real national climate policy managing the decline of fossil fuels, the transition is scattershot, messy, and full of carnage.

Power companies announced more than 13 coal plant retirements this year, in many cases moving up previously announced closures and shortening the window of time the communities that live near and work at those plants have to think about what comes next. In May, a company called GenOn gave workers at one of its coal-fired power plants in Maryland just 90 days’ notice that it was closing.

A new analysis published in the journal Science last week offers a potential roadmap for the incoming Biden administration to manage the wind-down of all fossil fuels plants, not just coal plants, more systematically. Even better, it shows that shutting down the nation’s fossil fuel–burning power plants in the next 15 years to achieve Biden’s goal of 100 percent clean electricity by 2035 isn’t as economically risky as previously thought.

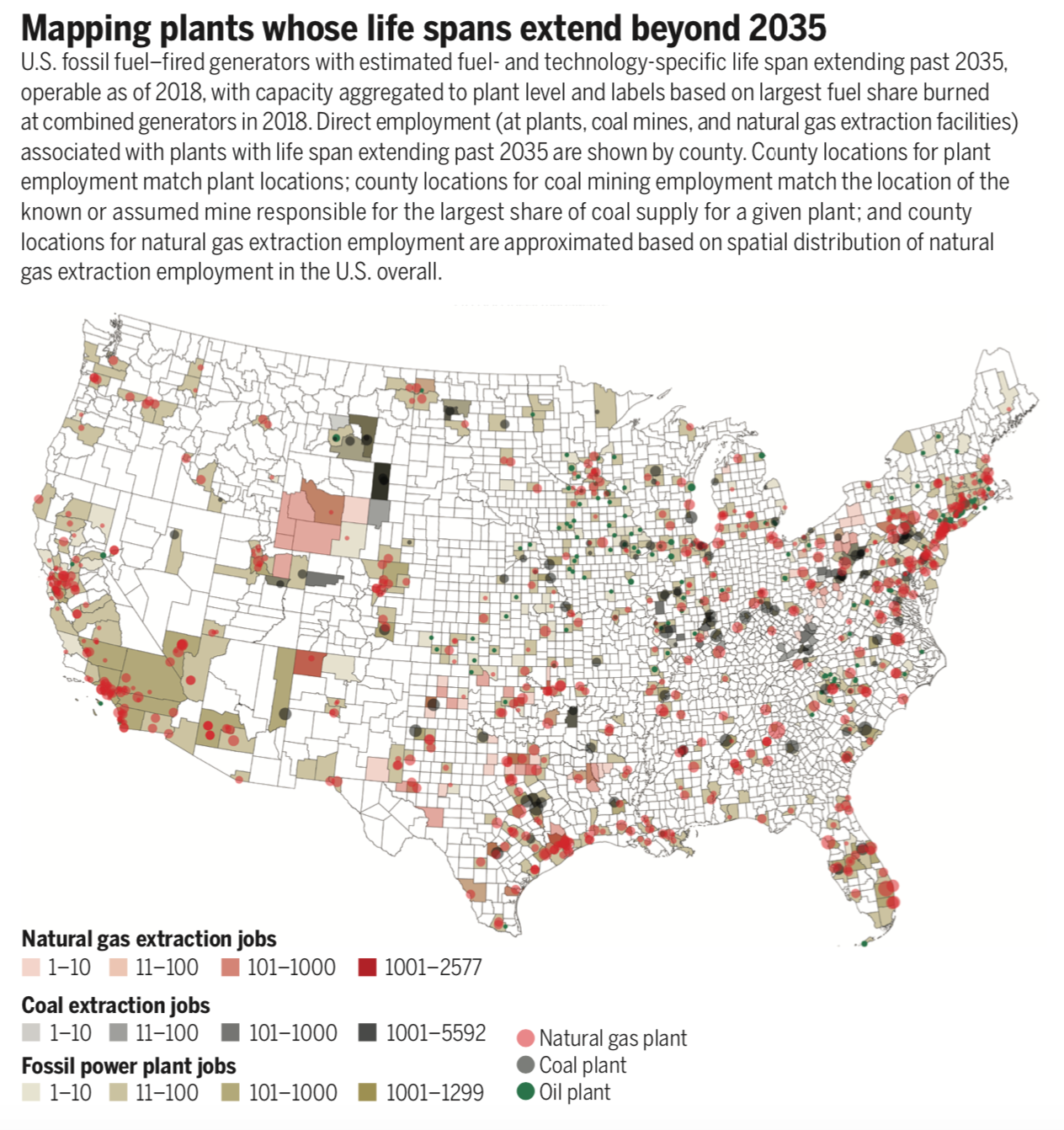

Emily Grubert, a civil engineer and environmental sociologist at Georgia Tech and the author of the study, mapped out every coal-, gas-, or petroleum-powered generator running in the U.S. in 2018, the most recent year for which complete data was available. She estimated when each one could be expected to retire, based on fuel, technology, and when it was built.

Power plants typically last 30 to 50 years, and construction costs are paid off over the course of their lifespans. If policy forces a plant owned by a utility to shut down early, that utility’s customers could remain on the hook to cover the debt, while also having to pay for whatever new source of energy is replacing it. The prematurely retired plant could thus become what’s known as a stranded asset. But Grubert found that the vast majority of plants — more than 70 percent — will actually reach the end of their expected lifespans before 2035, and should theoretically be paid off by or around then.

Emily Grubert / Science

“It’s really important when we have this kind of data,” said Mijin Cha, an assistant professor in urban and environmental policy at Occidental College who was not involved with the study, “because often things like stranded assets, they get used to kind of put fear into people’s minds about the inability to transition to a low-carbon future.” The study reveals that in fact, a 2035 decarbonization deadline would strand very few power generation assets — as long as companies stop building new fossil fuel-burning power plants starting now.

In his climate plan, Biden committed to making an “unprecedented investment in coal and power plant communities” including helping to diversify their economies and securing health and retirement benefits for workers. If power plants were forced to close at the end of their estimated lifespan or within five years of that date, as Grubert suggests in her study, the government could roll out these resources over time and target communities as their facilities close.

That would also give communities ample time to plan for the future. “If you know a plant is going to shut in the next 10 to 15 years, that’s very different than if you’re given 90 days notice,” said Cha, “in terms of what you can plan for, and what investment you can attract.” She said many of the communities with economies tied to the fossil fuel industry will need more basic investments, like expanded access to broadband internet, before they can even think about attracting new industries.

Grubert likened the process of a plant closure to the stages of grief: The announcement will be met with anger at first, but with enough time communities can accept what’s happening and move to a more productive place. “The thing that worries me the most is if there’s not a really, really durable commitment to decarbonization,” Grubert said. If outrage and protests can convince lawmakers to reverse decisions that close power plants, the possibility of a just transition for workers and communities goes out the window. “Then you are back where we started, which is basically just firing everybody one morning and telling them ‘good luck to you,’ which is a really bad outcome.”

The new study offers a strong case for the managed decline of fossil fuel–fired power plants by 2035, but questions remain about how to achieve it. Even if most fossil fuel plants will be old enough to retire before 2035, that doesn’t mean they will. Plant owners often keep them open for much longer — Grubert found that there’s already about 100 gigawatts worth of infrastructure past its prime, including a coal-fired generator in Nebraska from 1915. While many utilities say they plan to reduce their emissions to net-zero by 2050, a recent analysis by the Energy and Policy Institute, a nonprofit utility watchdog, found that almost none of those plans move quickly enough to achieve Biden’s goal of a carbon-free electric grid by 2035.

There’s also no single, swift action the Biden administration could take to require all fossil fuel–burning power plants to shut by 2035. Ari Peskoe, director of Harvard University’s Electricity Law Initiative, told Grist that instead, the government could try to approximate that deadline through environmental and economic regulations.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) could regulate greenhouse gas emissions, and states could choose to adopt even stricter rules. Some are already doing so — three coal plants in Colorado may be forced to shut down in 2028, two years earlier than previously planned, to meet the state’s climate targets and an air quality rule that seeks to improve visibility in Rocky Mountain National Park.

On the economic side, a power plant’s viability depends on what the owner is allowed to charge customers. Power plants that are owned by utilities are regulated by state agencies, while independent generators must follow the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s rules. Cheap renewables are already weakening the case to keep open old coal plants in regulatory proceedings, and with more subsidies for clean energy, or fewer for fossil fuels, that trend will continue.

The other side of the coin is preventing new gas-powered generators from being built. Peskoe said the EPA could put stricter rules on new plants, and he expects to see rule changes in interstate electricity markets that make the economics of building a new plant less favorable. “They can also stop pipeline expansion too, which is obviously related to power plant expansion,” he added.