The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced in late March that it would substantially relax enforcement during the COVID-19 pandemic. The decision was met with outrage. A coalition of nearly two dozen environmental justice, climate, and public interest groups even took the agency to court in response. With the EPA under fire, state officials across the country assured environmental advocates that their enforcement efforts would not let up, despite the fallout from the novel coronavirus.

But if preliminary data from Pennsylvania are any indication, state environmental agencies are likely falling well short of that promise.

“Staff are still working to protect Pennsylvania’s environment,” Patrick McDonnell, head of the state’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), wrote in an April letter to concerned environmental groups. Sure, inspections — the kind that DEP employees conduct to make sure that fracking sites, mines, and refineries aren’t polluting the air and water — were happening less frequently. But McDonnell insisted that the most essential enforcement was as robust as ever. “We are still on the ground at the sites most susceptible to environmental impacts,” he wrote.

McDonnell’s letter didn’t give the whole picture. A Grist analysis of the DEP’s own data shows that the agency conducted 37 percent fewer inspections in the six weeks after the state’s March 16 shutdown, compared to the same period in 2019.

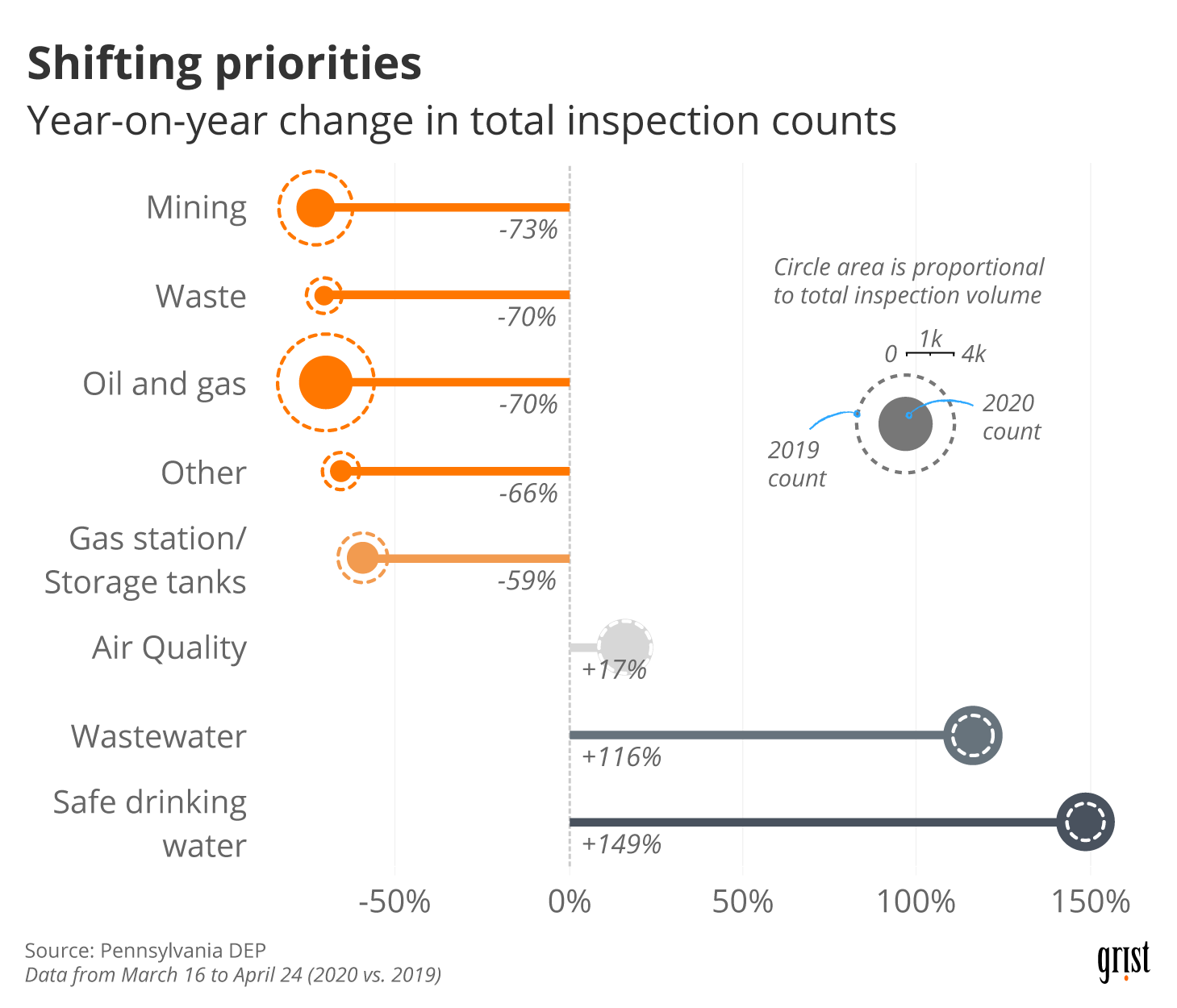

The biggest decreases in inspections were in the oil and gas and mining programs. These extractive industries are still operating largely as they did before the pandemic, having been deemed “essential” by the government. Inspections of these industries were down about 70 percent.

At the same time, the agency has continued to process applications for permits allowing drilling, construction, and mining companies to continue their operations. Since the shutdown, the DEP has tackled more than 5,260 such requests from businesses, which is about 20 percent less than before the pandemic. The agency said that the decrease is partly due to companies making fewer requests — and that some DEP programs have actually reduced turnaround times for permits.

“While we’ve got less inspections happening, less complaints being responded to than ever, we also have new permits being filed and new operations allowed to begin,” said Leann Leiter, a Pennsylvania-based organizer with the environmental nonprofit Earthworks. “That really just highlights the fact that this system is weighted toward development, and harm reduction is a second thought at best.”

After state governors began issuing shutdown orders, many instituted work-from-home policies for state agencies in an effort to contain the virus and protect employees. As a result, field inspections — a critical component of environmental law enforcement — took a back seat.

The DEP data suggest that this approach might be leaving residents more exposed to polluting industries during the pandemic.

Investigations in response to resident complaints are down significantly. In March and April of 2019, the agency conducted 169 such investigations. After the shutdown this March? Just 21. Though the DEP told Grist that the volume of complaints had decreased by about a third, inspections dropped off much more precipitously — by about 88 percent.

On the other hand, Grist’s review also found that DEP staff have been conducting more than three times as many file reviews since the shutdown began. A file review is a type of inspection that relies on businesses’ self-reported data. Reviews of air emissions reports — which refineries and chemical plants submit routinely in order to report the amount of pollutants leaving their stacks — increased 145 percent after the shutdown compared to the same period in 2019. Overall inspection numbers for wastewater facilities and public water systems more than doubled because of a dramatic increase in file reviews, even as onsite inspections dropped.

Megan Lehman, a spokesperson for the DEP, said that the increase in file reviews is a good example of how staff have adapted to new circumstances and prioritized inspections that could be completed from home. She praised DEP staff for performing “remarkably well” despite the “unplanned, instantaneous conversion to telework.”

“Due to the severity of the pandemic, our first responsibility is to protect the health of our employees and the general public by following the governor’s orders,” Lehman told Grist.

The agency is not processing records requests while its offices are closed. Lehman provided the data at Grist’s request.

In recent years, the DEP’s work has been imperiled by more than just the pandemic. This year’s decline in inspections comes at the tail end of a decade defined by budget cuts and staffing shortages. Since 2002, the number of employees at the agency has decreased by almost 30 percent, and its budget has been slashed by 40 percent.

Even as the agency exercised some creativity to continue operations remotely this month, the state’s Republican-dominated legislature passed a bill to suspend all new rulemaking — including environmental regulations — until 90 days after Governor Tom Wolf’s emergency declaration is lifted. Wolf, a Democrat, vetoed the bill this week, but another similar bill is pending and could effectively halt any action on the DEP’s request to raise fees on the oil and gas industry in order to hire 49 additional inspectors.

Environmental advocates say that lawmakers are capitalizing on the pandemic to kill the fee proposal and others like it. A slew of other pending bills threaten to take away the DEP’s authority to enter into an interstate greenhouse gas reduction program, slow down the agency’s ability to create new environmental rules, and force it to approve permits within 30 days.

“This system isn’t really adequate to protect people and climate even in normal times,” said Leiter. “Every few weeks it seems like we’re encountering some other legislative attack.”

David Hess, who headed the DEP under former Republican Governors Tom Ridge and Mark Schweiker, told Grist that he’s been “amazed” by the work the agency has been able to do during the pandemic.

“People get all upset about the Trump administration and the cuts they’re making at the federal level, but we’ve been going through Trump-like cuts for the last 12 years here in Pennsylvania,” he said. “I’ve been in and around these agencies for 45 years, and I’ve never seen a situation like this, where they went from a standing start to accomplishing what they are still accomplishing, with the resources that they have.”

Fox in the henhouse

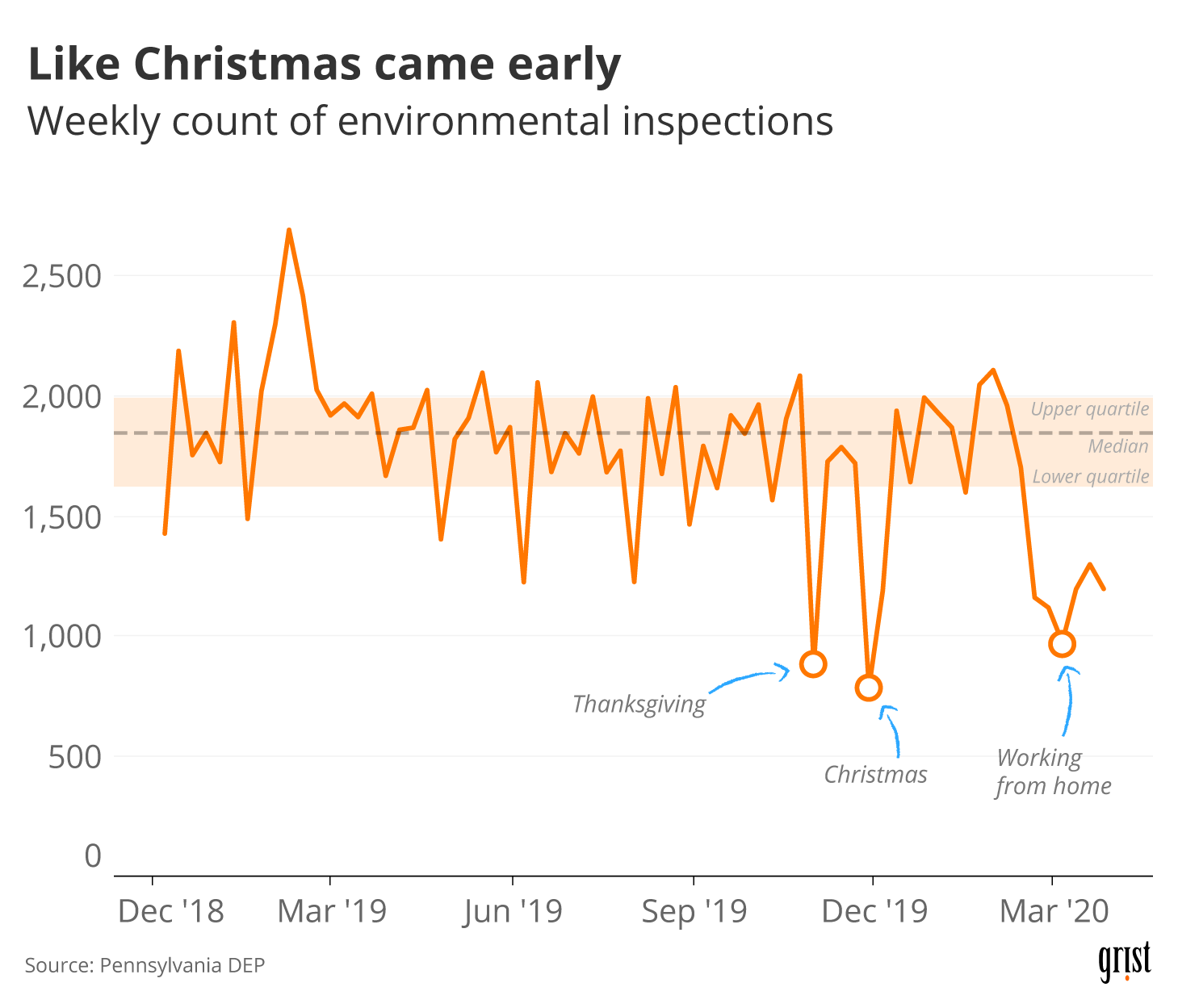

DEP staff began working from home on March 16, the day that Governor Wolf expanded his shutdown order to the entire state. Inspections took an immediate hit. That week the agency conducted about 1,160 inspections, a decrease of approximately 35 percent from its weekly average of 1,800 in 2019. Those numbers have remained steady ever since, hovering around 1,100 per week at the end of April. Inspections last dropped below 1,100 during the weeks of Thanksgiving and Christmas last year.

Clayton Aldern / Grist

The agency’s inspections can be roughly broken down by program — oil and gas, mining, safe drinking water, wastewater, and radiation protection, among others — as well as by type of inspection. Routine inspections, administrative file reviews, and complaint investigations are the three main categories of the latter.

In the six weeks after the shutdown, inspections in the oil and gas and mining programs decreased overall by 70 percent. These two programs also saw the most significant decline in routine inspections. The oil and gas program, for instance, conducted more than 3,000 routine onsite inspections between March 16 and April 24 of last year. Over the same time period this year, the department completed just 97 such inspections. However, at the same time, the oil and gas department conducted almost four times the number of file reviews compared to 2019 — jumping from 278 to 1,065.

Under the conditions outlined in their permits, businesses may be required to periodically report on any number of environmental metrics that help the DEP monitor their activities. For example, refineries are required to quantify and report the amount of pollutants escaping from their smokestacks. Environmental and public health advocates say that file reviews, which rely on self-reported data, can provide meaningful information about a company’s operations. They also say that file reviews are no substitute for field inspections.

File reviews are “simply not going to provide the same level of detail or encompass the same level of information about potential violations as a regulator going out and and reviewing what’s happening at the site in person,” said Lisa Widawsky Hallowell, a senior attorney at the Environmental Integrity Project, a nonprofit founded by former EPA attorneys. “That’s basically like the fox watching the henhouse.”

Lehman, the DEP spokesperson, said that staff faced multiple challenges during the shutdown’s first two weeks, when they abruptly shifted to teleworking. They faced technical challenges and internet disruptions when they began working from home, and field inspectors needed to secure protective equipment such as masks and gloves. Additionally, she said that “many DEP-regulated entities were required to suspend operations” in response to the shutdown order and therefore could not be inspected by the agency.

The DEP did not provide an estimate of the number of businesses that shut down and therefore could no longer be inspected. Still, the data show that the types of industries that the agency targeted in its inspections during normal times — oil and gas, coal mining, drinking water facilities, and wastewater systems — were generally considered “essential” by the state and not required to shut down.

“Most of what they inspect probably would have been operating,” said Hess, the former DEP secretary. The radiation division, which conducted 65 percent fewer inspections, may have seen a decline because many clinics and doctors’ offices closed during the shutdown. Overall, however, inspections wouldn’t have been significantly affected by closed businesses, Hess told Grist.

Investigations in response to complaints have also plummeted. The agency conducted just 21 inspections in response to complaints in the six weeks after the shutdown, an 88 percent decrease from 2019. That decrease is likely partially explained by a decrease in the number of complaints the agency has been receiving. According to Lehman, the agency received one-third fewer complaints the month after the shutdown, compared to last year. Additionally, some inspections in response to complaints may not have been logged as such in the database, she said.

But Lehman also acknowledged that, in response to the governor’s orders, the agency is only deploying inspectors into the field “when prudent” and to respond to emergencies — such as, for example, a tractor-trailer crash that results in a diesel spill.

That means that complaints from residents about odors from fracking sites and other chronic but less urgent environmental issues may not result in a site inspection. Members of the public are the agency’s eyes and ears on the ground, and with many residents sheltering in place near fracking operations, the decrease in DEP inspections means that they cannot rely on the agency to support them during the pandemic, according to advocates.

“We now have a situation where even the most responsive inspectors are being told not to respond, unless there’s some catastrophic failure of some sort,” said Lisa Graves Marucci, a community outreach coordinator at the Environmental Integrity Project. “The citizens are becoming even more frustrated because they are forced to live near some of these facilities. They have concerns, and they’ve been told someone will be there, should there be a problem. And now that human aspect of it is missing.”

Underfunded and understaffed

The discovery of the Marcellus shale play — estimated to be the largest natural gas reserve in the country — fundamentally changed the energy landscape in Pennsylvania. Beginning around 2008, the state faced an unprecedented energy boom. Seemingly overnight, large swaths of forest were razed and fracking operations began dotting the state’s mountainous landscape. Many wells were drilled right in people’s backyards.

Between 2009 and 2019, oil and gas companies drilled more than 19,000 wells in central and western Pennsylvania. The fracking frenzy filled the state’s coffers, and its budget grew 18 percent during this period. But state lawmakers simultaneously slashed the budget of the very agency charged with holding the oil and gas industry accountable.

The cuts had serious repercussions. In 2016, the EPA found that staff in the DEP’s safe drinking water program were being overworked and were handling more than double the number of cases averaged by their peers elsewhere in the country. As a result, DEP inspections were declining, the EPA said, and the number of unaddressed violations were increasing.

“This increased risk to public health is of concern to EPA,” the federal agency wrote in a letter to DEP leadership.

In response, the DEP hiked permit fees for public water system operators in order to hire more inspectors. That year the beleaguered agency also made a desperate plea to raise fees for oil and gas operators as well. As a result of low fees, the agency had reduced staffing by about 15 percent over three years and told lawmakers that it “struggles to meet its gas storage field inspection goals,” among other targets.

The DEP proposed doubling these permit fees. The agency estimated that it would receive 2,000 permit applications per year, which would generate an additional $25 million annually and allow the DEP to hire 49 more inspectors. That request was in the last stages of being finalized when the pandemic hit. With companies scaling back new drilling due to the oil price crash, it’s unclear whether the pending fee hike would generate the additional revenue the agency needs. The DEP has only processed about 400 applications so far this year.

The proposed fee also faced significant pushback from some lawmakers. Earlier this month, Republican legislators attempted to derail the fee increase, but Governor Wolf thwarted their efforts with a veto. Many Republican lawmakers believe that the DEP’s fee request would prevent further oil and gas industry growth in the state, and some have pushed the agency to follow the EPA’s lead and roll back enforcement during the pandemic. Representative Daryl Metcalfe, who chairs the House Environmental Resources and Energy Committee, demanded that the DEP “stand down” instead of “being an obstacle.”

“I would like to know specifically how DEP plans to aid our Commonwealth’s economic recovery efforts,” Metcalfe wrote in a letter to DEP Secretary McDonnell. “What regulations do you intend to roll back or repeal to allow our business climate to recover as quickly as possible? How will the department change the way it operates to encourage economic growth?”

Hess, the former DEP secretary, has followed the agency’s budget woes closely and said that staffing shortages have resulted in oil and gas inspectors managing double caseloads.

“That is not an acceptable situation,” he said.

Clayton Aldern contributed data reporting to this story.