The Komati coal-fired power plant, located 88 miles east of Johannesburg in South Africa’s coal heartland, has been called the flagship of the country’s budding energy transition. At its peak, the facility, which came online in 1961, produced 2 percent of the country’s power supply. It also supported thousands of people, from miners digging nearby seams to hawkers selling bananas by its front gates. Yet its owner, the state company Eskom, retired the plant in October 2022 after deeming the repairs needed to keep it running cost-prohibitive. Instead, it chose Komati for a different sort of makeover.

A $497 million project financed by the World Bank will, over the next five years, dismantle the plant and surround it with solar panels and wind turbines, a battery array, a green-jobs training center, and a factory that will employ hundreds of workers building community microgrids. President Cyril Ramaphosa hopes Komati will not only lead his country’s emergence as a clean energy heavyweight but show how to do so equitably and with the guiding input of communities and labor. Eskom calls Komati one of the largest efforts in the world to decommission and repurpose a coal plant, and says it could become a “global reference on how to transition fossil fuel assets.”

But when Malekutu Motubatse visited a nearby village in September, he found a ghost town. Motubatse, who represents some 35,000 miners and others as regional chair of the National Union of Mineworkers, says the closure cost at least 1,000 contractors their livelihoods and crashed the local economy. “People are demoralized, people are hungry,” he said of the 4,000 or so residents. “You can’t just close down a power station without an alternative. People can’t eat promises.” A recent report on Komati, commissioned by Ramaphosa, backs him up, saying Eskom wrongly shuttered the facility before new work opportunities were in place. But with four more coal plants scheduled to close in the area by 2030, Motubatse fears more harm to workers and communities lies in store.

If Komati is the flagship of South Africa’s plan to transition to a clean energy economy, it’s also an early indicator that things are off to a choppy start. For the last two years, the country has led a group of developing nations that are working with the Global North to prove it’s possible to accelerate this process while buffering workers and communities from the shakeup. In 2021, South Africa became the first to formalize this mission in a policy plan, signing an $8.5 billion deal with a cluster of G7 nations called the Just Energy Transition Partnership, or JETP. The program’s guiding logic is that many emerging states want to grow on a sustainable path but need cash to do it fast enough to benefit the climate.

JETPs are designed to support them with a burst of focused investment. The basic structure is that a group of rich nations — including, for example, the United States — pledges money to a developing partner, which comes up with a compendium of projects that it thinks can hasten its energy evolution and deliver specific emissions reductions. Partners review the list and match funding to projects over a window of three to five years. Ideally, they should unlock billions of dollars more in private-sector investment. It’s not yet known how well this will work, but that hasn’t stopped Indonesia, Vietnam, and Senegal from signing similar deals over the last two years. More announcements could be coming at COP28; India, Nigeria, and Kazakhstan are some of those rumored to be in the hunt. China’s signaled interest in financing similar programs. Last week, President Xi Jinping announced roughly $100 billion in climate financing to spur clean energy projects abroad, in an initiative that boosters say has some resemblances to the JETP.

No one expects these efforts to go smoothly. Even in rich countries energy infrastructure is notoriously slow to change, with transitions measured in decades rather than years. Experts have already observed frictions between the Global North and South — from squabbles over financing to differing visions of justice — and say this is slowing the flow of money and deployment of real-world projects.

In some cases, these frictions are evidence of tough, pragmatic negotiations; in others, they reveal deep divisions that could slow or even derail a country’s participation in the program. “This is your credibility,” Luhut Binsar Pandjaitan, Indonesia’s coordinating minister and its top JETP negotiator, snarled at G7 partners in a May interview with Bloomberg. “We don’t lose anything if the deal doesn’t materialize.”

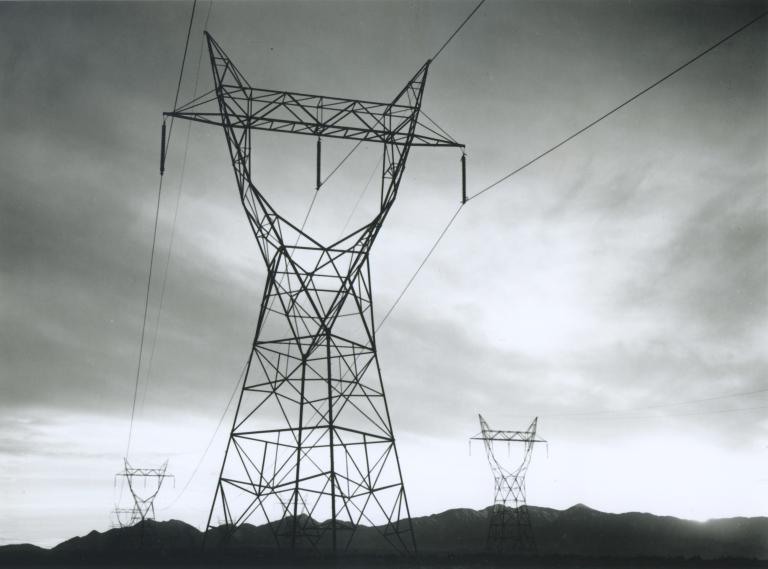

South Africa’s energy transition was driven by a combination of factors: a sense that its economy was overdependent on fossil fuels, direct exposure to climate impacts, and perhaps most immediately, practical necessity. Not only does the country generate 80 percent of its power from coal, but half of its plants are more than 40 years old and require intense upkeep that one expert likened to life support. As energy demand increases, this wheezing fleet is increasingly incapable of keeping up, and electricity gets rationed. This year has seen particularly severe stretches during which South Africans experienced up to 12 hours of power outages a day.

In towns like Komati, the local power station, also called Komati, is the axis around which the local economy revolves. Nationally, the shrinking coal-mining industry only employs about 80,000 workers, but the tally of everyone whose livelihoods are directly or indirectly tied to that fossil fuel — including families — totals two million to four million people by one estimate.

Ramaphosa, a former general secretary of the National Union of Mineworkers who also played a key role in negotiating the end of apartheid, has said the energy transition could simultaneously advance South Africa’s climate, economic, and social justice goals. Analyses cited by his Presidential Climate Commission say the shift from coal to renewable energy could create up to 1.4 million more jobs than it eliminates. Third-party assessments suggest that developing new industries in electric cars and green hydrogen could create millions more jobs. In an October 2021 public letter, Ramaphosa said the country would begin this long-term evolution by converting roughly 10 retiring coal plants into nodes of green infrastructure, featuring solar, wind power, and energy storage — starting with Komati.

South Africa could do even more, Ramaphosa wrote, if rich countries chipped in. A month later, at COP26 in Glasgow, it became clear what he was talking about when South Africa signed its JETP. Success in South Africa, said European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, would offer a “template” for others in the developing world.

Two years in, there’s little to show for it. Less money is moving than expected, said Leo Roberts of E3G, a think tank focused on addressing climate change, and there’s no physical infrastructure or up-and-running programs to evince a transition in progress.

One hangup is money. When South African officials read the fine print on the $8.5 billion deal they’d signed, they found just 4 percent came in the form of grants that don’t have to be repaid. The remaining 96 percent looked much like the loans South Africa could have obtained on its own, and some was money rebundled from previous programs, said Roberts, E3G’s program lead for fossil fuel transition.

This skews the funding package toward capital equipment. Because loans must be paid back, lenders favor investments with high returns. Solar and wind farms qualify, said Roberts, as do grid upgrades to some extent. Activities that emphasize equity, like training workers or supporting small businesses, don’t have direct investment returns, and so are less likely to get funded.

But it would be a mistake to view such programs as charity, said Mandy Rambharos, a former Eskom official who helped launch its energy transition program. “The return on investment is not in terms of financial benefit, but social license to operate,” said Rambharos, now vice president of global climate cooperation at the Environmental Defense Fund. “There is a return: Otherwise your [infrastructure] projects are not going to fly.”

Perhaps in response to this concern, last month the Netherlands and Denmark announced about $180 million in grants for South Africa’s JETP, Bloomberg reported.

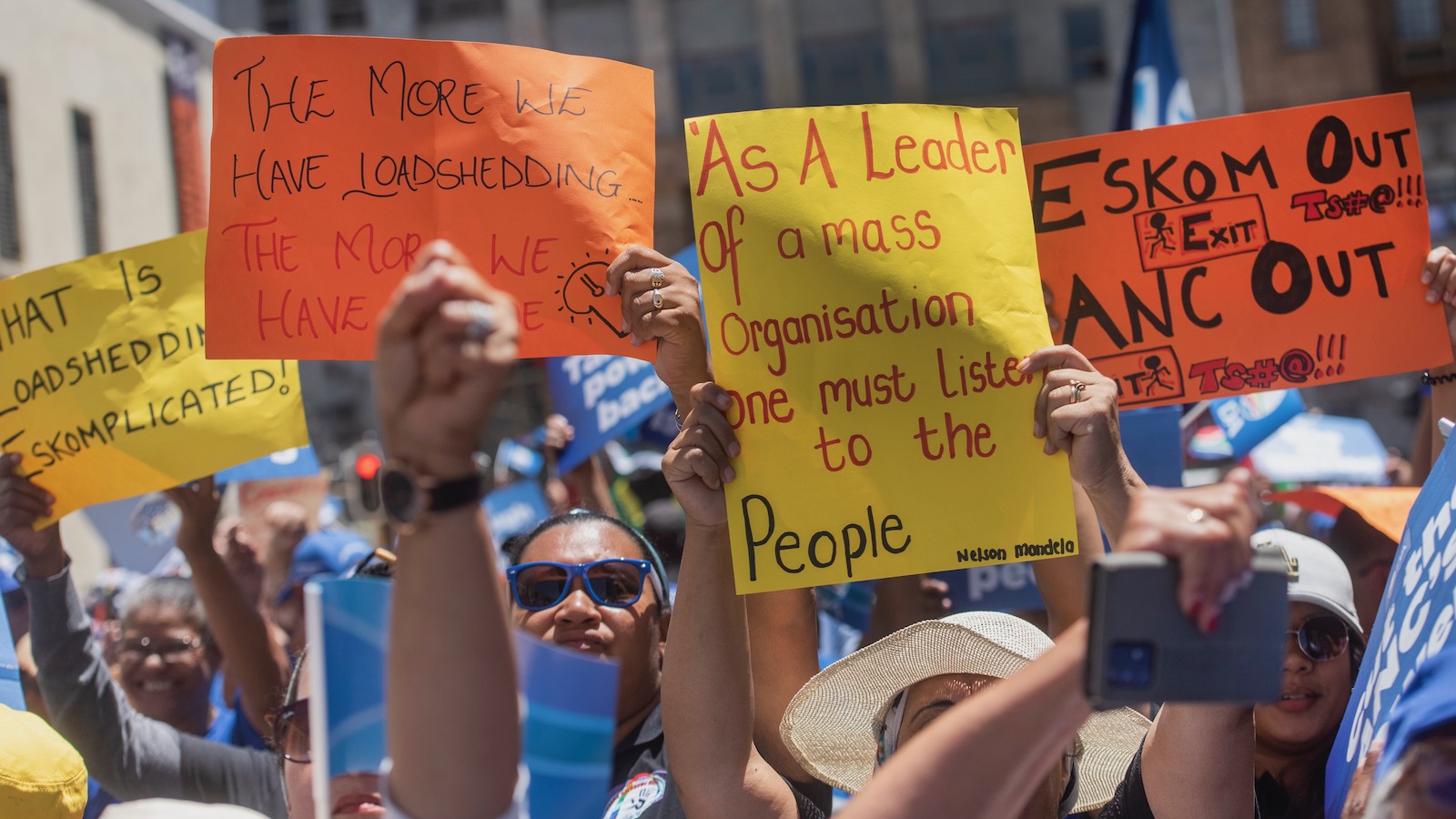

Recent events have revealed domestic discomfort with the energy transition, too. In the towns near Komati, community leaders have fumed that they aren’t seeing credible plans for creating jobs. Mineworkers have accused the government of selling out to the West and institutions like the International Monetary Fund, prioritizing climate goals while ignoring devastating unemployment in coal country. (The official unemployment rate in Mpumalanga province, which produces 80 percent of South Africa’s coal, hit 38.5 percent this year.) In July, the national electricity czar — whom Ramaphosa named in March to fix the country’s crippling power shortages — said the proposed energy transition was harming both people and the grid. “If I had my way, we’d go and restart Komati,” he said. “We have international obligations but, I’m sorry, we have an obligation to the South African people.” Those words gave heart to one local leader near Komati, who said, “The plant should be opened, because coal is the future.”

As Eskom held public-engagement meetings in Komati town this summer, a number of locals blasted them for paltry training programs and distant promises of opportunity. At one event, recorded by journalist Elna Schütz, company representatives seemed shaken by the withering critiques. “What did we miss?” blurted one official against the rising voices. “Help us understand.”

In July, Ramaphosa sent a special delegation to Komati to assess progress. Its September report said the project, while flawed, does have green shoots. According to Eskom, which did not respond to a list of questions from Grist, a facility that can produce container-sized solar microgrids, each capable of powering 50 rural homes, is ready. A green-jobs skills center has begun training its trainers. But to union rep Motubatse, these might as well be on Mars. “There is nothing there,” he said. “There’s no way to go there and find work.”

South Africa is hardly the only country having headaches. Indonesia is involved in multiple early-stage energy-transition programs, including a $20 billion JETP it signed in November 2022. Outside analysts say these efforts have produced little besides paperwork. A major investment plan, expected in August, has been pushed to later this month. Last November, the country teamed with the Asian Development Bank to devise a financial plan to retire a 660-megawatt coal plant up to 15 years early. It’s hoped this could become a test case for shuttering similar generators in the region. But no financing has been announced to underwrite the proposal.

A key problem is that Indonesia’s coal plants, unlike South Africa’s, are relatively new. Many have locked in 20- or 25-year contracts with the state to buy their electricity and just begun their lives as profitable assets. One of the JETP’s core missions is to eke out financial deals that retire these facilities early. Putra Adhiguna, an analyst with the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, is unsure what kind of offer could compel an owner to abandon that kind of moneymaker. “There’s just no sheer financial rationale to do this,” he said. One Asian Development Bank official has likened it to persuading someone to leave their apartment before the lease is up.

Behind this has loomed an even thornier issue: Indonesia is planning a massive coal buildout. The country’s volcanic origins have blessed it with some of the world’s biggest deposits of nickel and aluminum, two elements essential to batteries. But smelting them takes heat. Industrial producers are building fleets of private, or “captive,” coal plants that generate electricity, heat, or both. Tiza Mafira, Indonesia director at the Climate Policy Initiative, estimates that the JETP, if successful, could retire up to 5 gigawatts of coal-generated power. But the potential pipeline of captive facilities is quadruple that. “To invest in an early coal retirement knowing there’s more in the pipeline than you’ll retire is not exactly great,” said Mafira.

But blame can cut both ways, she added. In their eagerness to fund renewable energy, she said, G7 partners have shortchanged the amount devoted to coal retirements, causing frustration on the Indonesian side.

Late last month, Reuters reported that Indonesia will propose one solution to break the impasse: simply excluding the captive coal plants from the JETP scheme.

Then there’s the two newest JETP implementers, Vietnam and Senegal, where the energy transition has caused friction in different ways.

In recent years, Vietnam has experienced a wind and solar boom that’s the envy of Southeast Asia. Its success helped seal a $15.5 billion JETP deal with the European Union, United Kingdom, United States, Japan, and others last December. Core goals include writing off 7,000 megawatts of planned coal and increasing renewable generation to nearly half the grid by 2030.

Analysts say this green shift was driven by the tireless work of Vietnamese climate campaigners who — working within the narrow political space afforded by the one-party government — persuaded leaders that renewable energy would benefit the air and the economy. But in the last year, Vietnam has drawn censure from its JETP partners for arresting a half dozen of these advocates, mostly on tax charges that human-rights groups consider baloney. Some of these groups have called on JETP funders to pause implementation until the crackdown ceases.

Senegal’s $2.7 billion (€2.5 billion) JETP, signed in June with France, Germany, Canada, and the broader EU, drew notice for a different reason. Although the deal committed the country to the ambitious goal of getting 40 percent of its power from renewables by 2030, it also affirmed its plans to use natural gas as a transition fuel. (Senegal wants to refashion plants that burn heavy fuel oil to use methane, which the JETP partners claim will reduce greenhouse gas emissions.) Defending this choice, French President Emmanuel Macron promptly stepped in it: “We will allow it to develop its gas resources because gas is a transitional energy,” he said. The comment rankled some in Senegal and elsewhere, as it sounded less like that of a partner and more like that of a former colonizer.

If the gas has European partners gritting their teeth, Senegalese leaders consider it the piece that sealed the deal. The nation’s recently discovered gas fields represent one-fifth of a percent of global resources, according to Rystad Energy, a consultancy. But for politicians eager to expand electricity access and industrialize the economy, they represent a multibillion-dollar development fund. Public opinion surveys and stakeholder engagements suggest many Senegalese support developing the country’s hydrocarbon resources as well as clean energy.

The triumph of the final JETP, argues Secou Sarr, executive secretary of Senegalese NGO Enda Tiers Monde, is that Senegal got to choose its path forward, as developing countries too often don’t. “We are not just passive subjects,” Sarr wrote in a June essay. “We will lead the way in shaping the future of our country.”

It’s too early to judge if the JETP or similar efforts will succeed in fostering a just transition. It’s not too early, though, to make an observation: Nobody’s done this before, and it shows. The U.S. and the U.K., for example, are two countries where the collapse of the coal industry left lasting wounds. Germany is sometimes upheld as a model for green transition, but the ability to transpose that experience to a developing country is unproven.

In South Africa, there is a growing sense that there will have to be learning, and not all of it will be painless. After a September briefing on Komati, South African Environment Minister Barbara Creecy struck a sober note. “If this is not a blueprint for the future,” she said, “we have to learn from this experience what would be a blueprint.”