Last year, when former Bolivian president Evo Morales was forced to resign, it was unclear whether the socialist leader’s dream of transforming his country into a powerhouse lithium producer would survive. Last month, the world got its answer when Bolivians overwhelmingly voted to elect Luis Arce, the candidate representing the Movement Toward Socialism (MAS) party and Morales’ handpicked successor.

The lithium dream is not dead. In fact, it’s bigger than ever. But whether Arce’s administration can succeed in developing Bolivia’s lithium riches — and do so in a way that benefits Bolivian workers and frontline communities — remains uncertain.

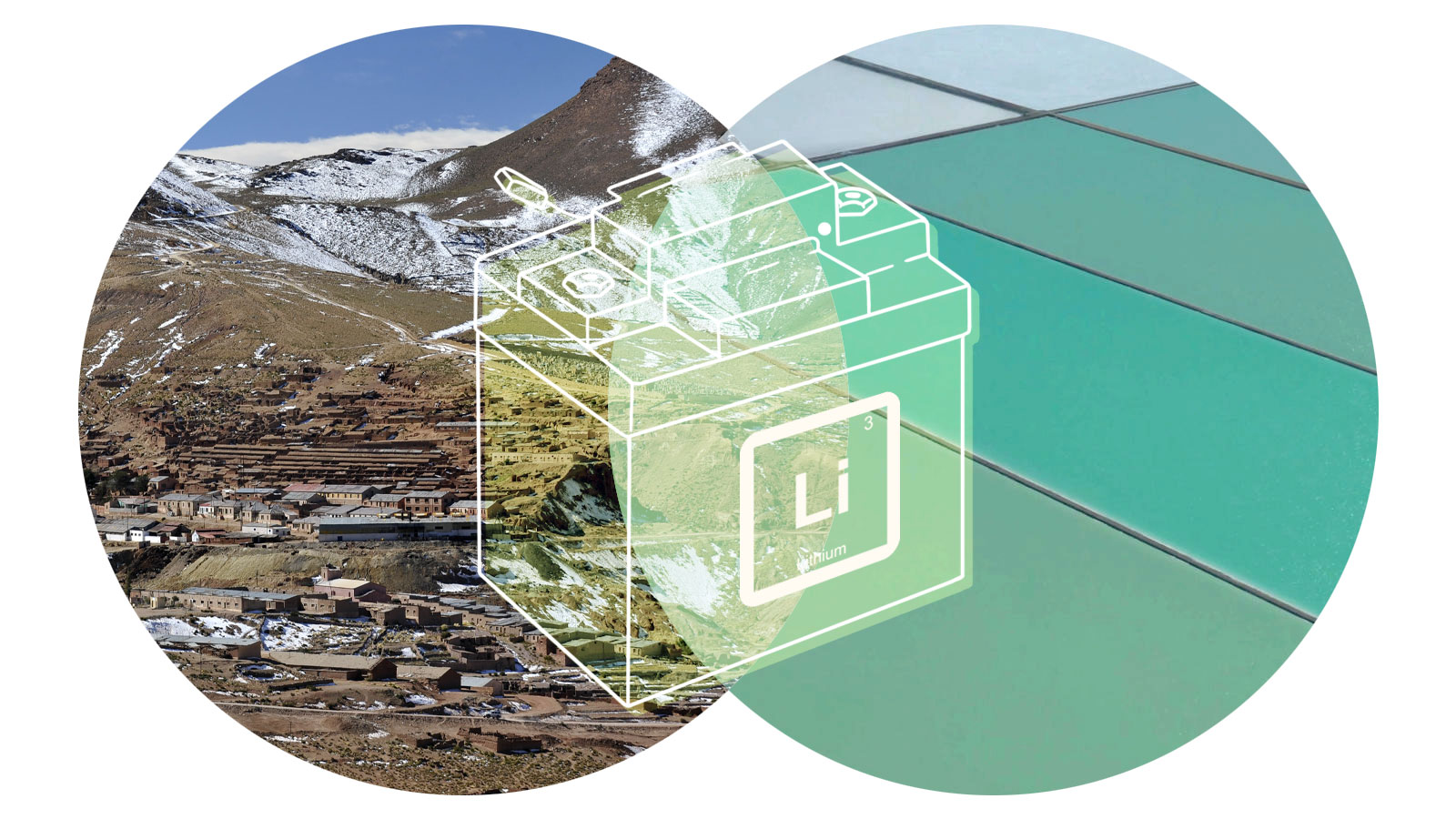

Found in electric vehicle (EV) batteries and batteries that store energy generated by solar panels and wind turbines, lithium is one of the key resources driving the global clean energy transition. Bolivia has more of it than any other country, but the nation has long struggled to produce lithium commercially. Arce, like Morales before him, wants to change that. In a strategy document released on the campaign trail, the new president called for massively ramping up Bolivia’s lithium production capacity in order to supply 40 percent of the global market by 2030, turning the small South American nation into the “lithium capital of the world.” Bolivia will use that lithium to spin up Latin America’s first EV battery production hub, generating wealth and opportunities for the people of Bolivia. That includes, Arce estimates, 130,000 jobs in lithium extraction, processing, construction, and logistics by 2025.

“He is trying to show the public they’re going to be a leader in lithium,” said Kirsten Francescone, the Latin American coordinator at MiningWatch Canada. “Lithium, over and above every other metal and mineral the country produces, is going to be the country’s way out” of economic turmoil.

In geologic terms, Bolivia’s lithium production potential is enormous. The country is home to the world’s largest salt flat, the Salar de Uyuni, which contains an estimated 23 million tons (21 million metric tons) of lithium in briny fluid deposits just beneath its crystalline surface. Still more lithium can be found in Coipasa and Pastos Grandes, two other Bolivian salt flats to the north and south of Uyuni, respectively. By comparison, Australia — currently the world’s largest producer — has just 6.9 million tons (6.3 million metric tons) of lithium in hard rock deposits.

But for years, Bolivia has struggled to get its lithium out of the ground. Part of the problem is chemistry: The Uyuni’s brines contain high levels of magnesium, an impurity that’s difficult to separate from lithium. The region’s relatively rainy climate also means that traditional methods for concentrating lithium from brines — in large, open air evaporation ponds — don’t work as well as they do in the drier salt flats of Argentina and Chile, where lithium is already being produced commercially.

Bolivia has also faced political challenges commercializing its lithium that stem from deep divisions over how much control local, state, and international actors should have. As president, Morales believed the balance of power should tilt strongly toward the state, which is why, over a decade ago, he laid out a national strategy for lithium development. His goal was to build an entire lithium value chain from salts to batteries in Bolivia, all under the auspices of a state-run company (now called Yacimientos del Litio Boliviano or YLB).

But the effort was fraught with setbacks that close observers say stemmed both from technical challenges with Bolivia’s unruly brines and bureaucratic mismanagement within YLB. By the final days of Morales’ presidency, the nation had only built a few pilot plants for producing lithium and battery materials. It began building its first commercial lithium plant in 2018, but the plant remains unfinished to this day.

As the lithium project lagged, Morales became more open to foreign partnerships. In late 2018, he entered YLB into a joint venture with a German firm called ACI Systems, which claimed to have new technology that could help Bolivia extract large quantities of lithium from waste brines left over from evaporation processes.

The deal, while popular with the German government, was harshly criticized within Bolivia, particularly by locals in the mining department of Potosí, where Uyuni is located. Many Potosínos felt they were not adequately consulted about the project and that the department wouldn’t be receiving enough royalties from it. Locals started to mobilize against Morales, ultimately pressuring him to annul the joint venture last November. About a week later, Morales was forced to resign amidst broader national unrest over contested election results and military intervention that some have described as a coup.

Arce, an economist and Morales’ former finance minister, now has to pick up the pieces of the lithium project, which appears to have languished under the right-wing government that took control of Bolivia after Morales’ ousting. Despite laying out some ambitious goals, it’s not exactly clear how he’ll proceed.

Broadly speaking, Arce intends to move forward with Morales’ original plan of producing lithium and batteries in Bolivia. But Francescone of MiningWatch Canada suspects that Arce will be more open to international partnerships than his predecessor was, noting that he represented the “most conservative arm” of the MAS party in terms of economic policy. His recent lithium strategy document supports this view: In Spanish, it calls for Bolivia to associate with “strategic companies that provide technology and markets from any region of the world but without privatization.”

Another hint that the new administration will take a more neoliberal approach to lithium came in July, when Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, a leading advisory firm for the battery and EV industries, announced it was advising then-candidate Arce on a “Lithium First Industrial Strategy.” Arce’s decision to partner with Benchmark, a firm that’s deeply embedded in the world of big business, “complicates a simplistic ‘resource nationalism’ interpretation of Arce’s plan,” said Thea Riofrancos, a political scientist at the Providence College in Rhode Island who studies the lithium industry. Reached for comment, Benchmark declined to elaborate on what its role will look like moving forward.

Arce might even try to restart the German joint venture. “He hasn’t said no to that,” Francescone said. “But I do think they’re going to be treading carefully because of what happened last year.”

ACI Systems, meanwhile, told Grist that it was waiting “until the new Bolivian government is officially established” to reach out again. Juan Carlos Zuleta, a Bolivian economist who briefly led YLB under the interim government and has strongly criticized the partnership with ACI Systems, told Grist he suspects that Germany is already exerting pressure on the new administration to re-adopt the deal.

Riofrancos suspects that compared to a more centrist or right-wing president, Arce will do a better job negotiating deals with foreign companies that are beneficial to Bolivians. Francescone, however, thinks that will depend on how much Bolivia’s economic fortunes worsen as the pandemic wears on “and how desperate the government becomes to get this stuff out of the ground, if it becomes feasible.”

Arce’s ambitions may also be tempered by the realities of the global lithium market. While analysts have long predicted that lithium demand will skyrocket as the EV industry takes off, so far, the world’s lithium producers are supplying more than enough of the mineral to meet global demand. With the pandemic causing a temporary drop in EV sales in a year they were expected to surge, the anticipated lithium crunch might be delayed even further. And until it arrives, lithium prices are likely to remain low, which could make it harder for newcomers like Bolivia to gain a foothold in the market.

“What we know from extractive industries in general is that the higher the prices for the commodity the more negotiating power the state has,” Riofrancos said. “What I’m concerned about for Bolivia’s sake is that the prices will continue to be low for lithium.”

Despite all the uncertainty, Zuleta, the Bolivian economist, feels cautiously optimistic. “My feeling is that Arce has a good opportunity to do things better,” he said. “And I really hope he will do that, and he will inform himself before jumping to conclusions.”