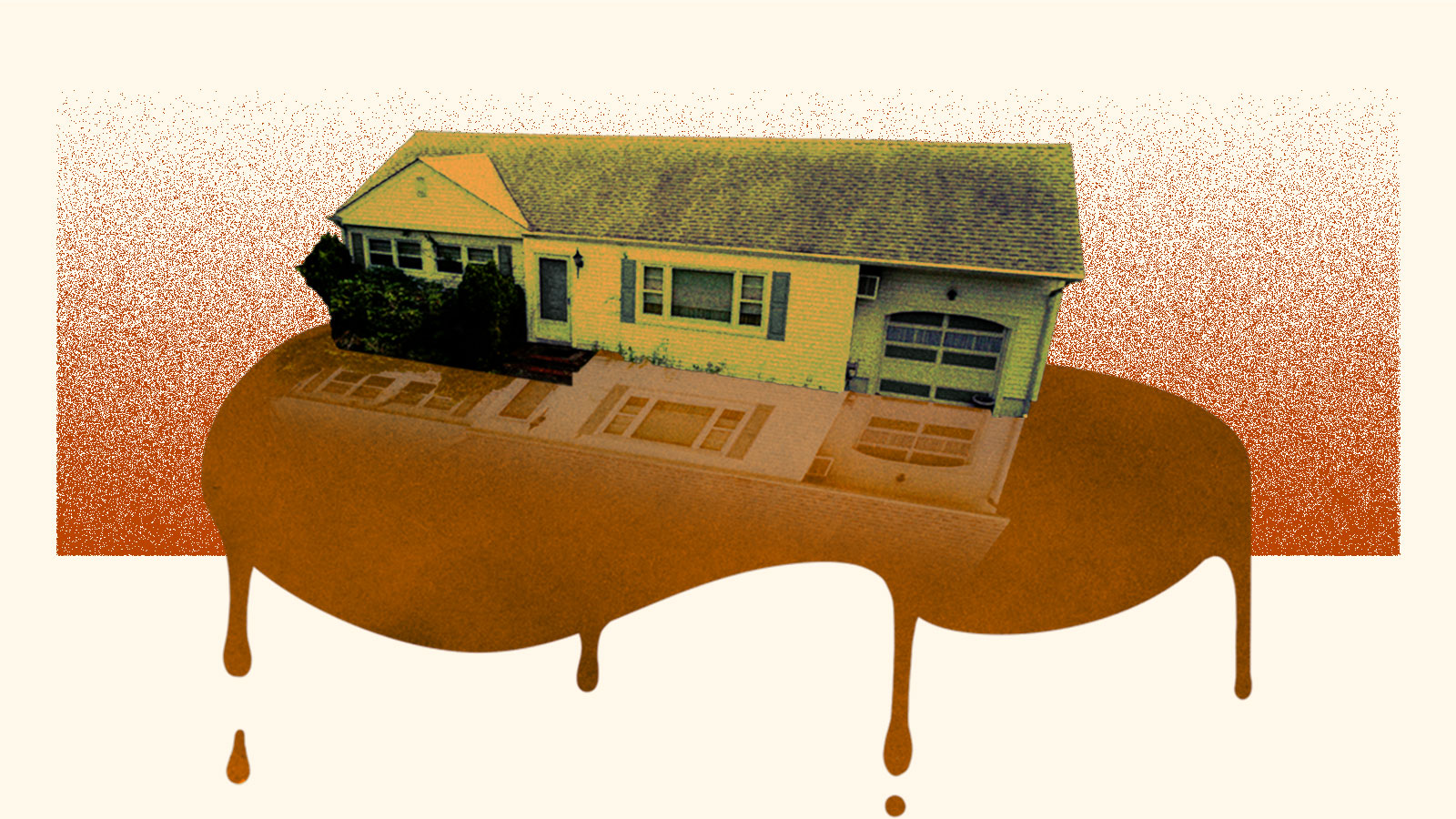

Cahokia Heights, a small city in southern Illinois, has gone through a lot of changes this year. Its new name is the result of a merger of the three towns of Centreville, Alorton, and Cahokia — a move that bolstered the St. Louis-area suburb’s municipal budget and gave residents hope for more adequate services. One thing that hasn’t changed, however, is the regular occurrence of sewage overflows that line its streets with human excrement — a problem that has plagued the area’s predominantly Black residents for four decades and even pushed some to purchase boats to navigate feces-filled waters when roads become impassable.

Since January 26, at least 28 sewer overflows have occurred in Cahokia Heights. The city is not alone: Communities of color in the U.S. are disproportionately burdened by aging and failing wastewater infrastructure. Wastewater networks across the country received a D+ grade in an analysis done by the American Society of Civil Engineers — and these problems are being exacerbated by increasingly frequent severe weather events linked to climate change.

In March, Cahokia Heights residents thought a solution was on the horizon. City officials claimed that with the merger of the three towns, the new city would be able to qualify for a $22 million grant from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA, to improve their sewage system, which has deteriorated for decades amidst reports of neglect and corruption by elected officials. That solution went down the proverbial toilet, however, when FEMA rejected the city’s grant application. This month, the Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, stepped in. Over the past three weeks, the federal agency has issued two orders intended to prevent drinking water contamination and stop sewage overflows. Two major obstacles remain: No financial support is attached to the orders, and no specific deadlines for compliance have been set by the EPA.

Yvette Lyles, a resident of Centreville (once dubbed the “poorest town in America”) for over 25 years, expressed disappointment at the government’s failure to commit substantial resources to the problem.

“It’s a heartbreak when they give you a name as being the poorest city in America — and you have money dangled in front of you that could’ve really helped our community, and then we never see it,” she told Grist.

In July, Lyles joined more than two dozen other residents in bringing a federal lawsuit against the city and local water district for failing to maintain the sewage system over the last 30 years. “It is time for them to poop or get off the pot,” she said of local officials.

The flooding has periodically forced Lyles from her home and threatened her health, as well as that of her family members. Cahokia Heights residents are exposed to heightened levels of bacteria and mold, and local doctors have speculated that the area’s water may even be linked to heart attacks.

“If I was younger and I wasn’t old and disabled, I’d be up out of here,” Lyles added. “But my home is paid for, and I can’t afford to go nowhere else on social security. So all I’m left to do is wait for them to do the right thing.”

The EPA is mandating that the city submit plans to control sanitary sewer overflows, which leads to water backing up in residents’ homes and yards. One of the biggest issues facing the system is that the area’s pump stations — which are designed to guide sewage away from local streets and homes — haven’t been updated since World War II. Additionally, the order calls on the city to train sewer staff on sewer-system inspections and develop a routine inspection and maintenance plan, as well as plans to better address complaints and work orders from residents. Because the city sits in a low-lying area, short rains can cause flash flooding; the EPA says the city needs to be better prepared for these weather-related events.

“This order will assist the city in focusing on identifying the most urgent needs for repair of the sewer system in order to protect the public’s health,” said EPA Region 5 Administrator Cheryl Newton in a press release.

However, without substantial money allocated to fund these improvements, residents fear their city will see more of the same. In 1989, the EPA awarded a grant to a neighboring town, which shares the same water system as Cahokia Heights, to repair the sewage system. But rather than fix the problems, officials used the funds to alleviate other debts.

Cahokia Heights Mayor Curtis McCall — who some residents eye with suspicion, given that he once chaired the agency that manages the city’s dilapidated sewer system — has said that the flooding issues are his top priority. He’s promised to use all of the funding allocated to the city through the American Rescue Plan Act, or ARPA, to address the problem. And if the U.S. Senate’s bipartisan infrastructure package ever goes into effect, $56 billion would be used to update aging drinking water, wastewater, and stormwater systems across the country. But as it stands now, ARPA funding available to Cahokia Heights amounts to just $2.8 million — less than 15 percent of the money the city originally expected from FEMA.

For Lyles and other Cahokia Heights residents, it’s back to the waiting game. They’re fully aware that substantial support from the federal government can take years, if it ever comes at all.

“We live in the richest country in the world, but not everyone is given the resources they deserve,” Lyles said. “We are human beings and citizens of this country, we’re not livestock.”