After years of bureaucratic delays, a federal lawsuit, civil rights investigation, sporadic hunger strikes by more than 100 residents, and countless protests outside Mayor Lori Lightfoot’s home, Chicago’s Department of Public Health has denied an operating permit to a controversial scrapyard that prompted national outrage and accusations of environmental racism.

The announcement last Friday ends a more than two-year battle by community and environmental activists to stop the relocation of a scrapyard, owned by Resource Management Group, from Chicago’s predominantly white and wealthy North Side to the largely low-income and Latino Southeast Side.

“The Southeast Side has won through community power,” resident and community activist Oscar Sanchez said in a statement. “The feeling is surreal. We will continue to fight for the communities we deserve.” Sanchez, who Grist profiled last March, was one of roughly 20 activists who went without food for 30 days last spring in an attempt to get the attention of Mayor Lightfoot and her administration.

The hunger strike, which received international attention, helped push the city to conduct a health assessment focused on the scrapyard’s potential impacts on the Southeast Side. The new facility has already been constructed, thanks in part to the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency, which approved a permit 20 months ago for the site’s relocation. But the health assessment, released in part last Tuesday, persuaded city officials to ultimately deny the company’s operating permit.

The Department of Public Health concluded that the facility, which was expected to recycle 2 billion pounds of metal products annually, would lead to “adverse changes in air quality and quality of life,” presenting an “unacceptable risk” to nearby residents.

Friday’s move prompted immediate praise from President Joe Biden’s handpicked Environmental Protection Agency head, Michael Regan. Last May, Regan called on Lightfoot to conduct a thorough review of the proposal, raising concerns of “environmental injustices” in the community, which already has some of the “highest levels” of pollution indicators in the country. “This is what environmental justice looks like,” Regan said in a statement on Friday, “All levels of government working together to protect vulnerable communities from pollution in their backyards.”

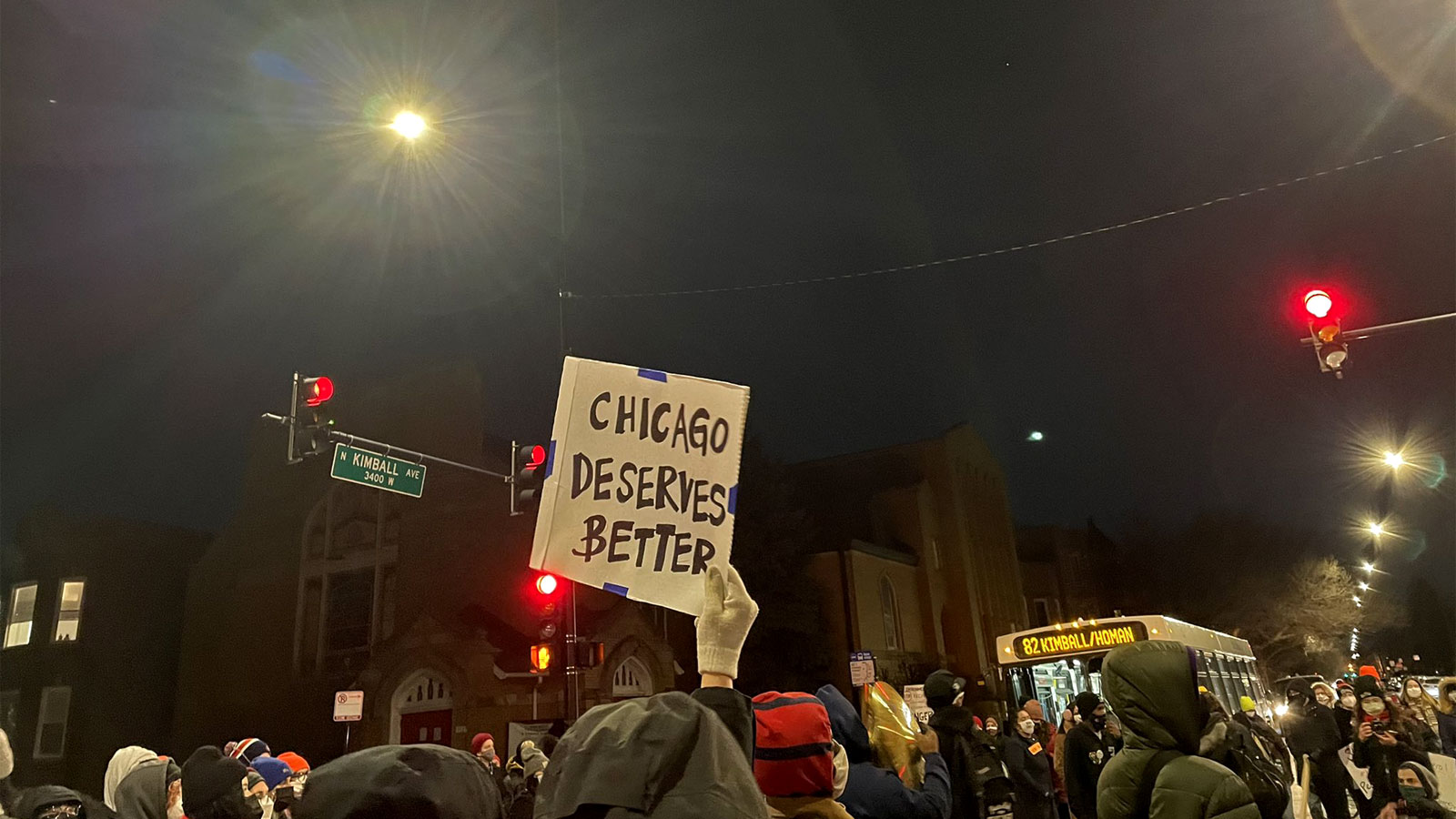

However, while government officials have praised the move as an example of effective regulation, Chicago residents have been quick to point out that without constant community pushback, the scrapyard would likely be operating today. The federal EPA’s interest only came after residents’ constant pleas for support —support they failed to receive from their local officials.

According to messages released by the Chicago Tribune in December, the community’s City Council representative, Sadlowski Garza, texted Lightfoot about the Southeast Side’s plans to foil the scrapyard. “They disseminate the wrong information,” her text message read. “They don’t play well with others so f–k them.”

To which Lightfoot replied, “I am riding with you til the end!”

The interaction underpinned the uphill battle that residents faced. “No community should ever have to go through anything like that again,” Olga Bautista, executive director of the Chicago-based Southeast Environmental Task Force, wrote to Grist on Twitter. “Shame on the politicians that allowed this to happen.”

According to the recently released White House Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool, the census tract around the proposed site is already exposed to more diesel pollution, and home to more industrial sites, than 95 percent of the country.

“Although we are celebrating this decision, the community continues to deal with the toxic legacy that has allowed pollution to accumulate in our community,” a coalition of 12 Chicago-based environmental groups organizing to block the scrapyard wrote on Friday. “We will not stop fighting for our right to clean air, and we will continue to fight until the health of Chicago communities like ours can live in a healthy environment.”

The result of the city’s environmental and health probe found that the new facility would lead to “no appreciable risk” in increasing health challenges in the already disproportionately burdened community. Although, oddly enough, the health impact assessment concluded that the site would have added to the community’s air, water, noise, and soil pollution, while also negatively impacting residents’ mental health.

While attention should be focused on the victory —even considering an expected appeal from the scrapyard’s ownership group —much more energy should be focused on reversing legacy pollution and preventing situations like these from arising in the first place, the community coalition said.

“The City of Chicago must be dedicated to policies that prevent a situation like this from happening in environmental justice communities.”