This story is part of Record High, a Grist series examining extreme heat and its impact on how — and where — we live.

Janae Van de Kerk works as a passenger service assistant at Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport. It’s demanding work, requiring her to push wheelchair-bound passengers wherever they need to go — through terminals and jetways, on tarmacs, into parking lots. During the city’s record-breaking hot streak this summer, Vandekirk spent most days nursing a headache or feeling sweat soak her uniform as she slogged through temperatures as high as 118 degrees Fahrenheit.

By way of protection, the airport gave her and her coworkers a 10-minute briefing on the basics: Drink fluids. If you’re not feeling well, sit down.

Ah, but there’s a catch.

“We’re not allowed to sit down unless we’re on an official break,” said Van de Kerk, and those come few and far between. By the time workers who request a breather get to the one break room available to them, their 20-minute allotment is all but over.

On August 24, Van de Kerk and 11 of her fellow airport service workers — from passenger service assistants like her to baggage handlers and cabin cleaners — filed a complaint with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, or OSHA. The employees, supported by Service Employees International Union, requested an inspection of working conditions they say leave them vulnerable to heat illness and exhaustion.

It is the first heat-related OSHA complaint from U.S. airport workers. The move comes after years of increasingly unbearable summers in Arizona and the Southwest that have seen temperatures increasingly ascending well into triple digits, but it could have ramifications much farther afield. Advocates hope it could motivate the agency, which governs workplace safety, to consider a blanket federal extreme heat standard for American workers. Such calls have come to a head in the record-shattering summer of 2023 and follow protests in Phoenix and beyond. A thirst strike in Washington, D.C., led by Texas Representative Greg Casar called attention to similar workers’ plights in his home state, while airport service workers at Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport have spoken out about their conditions.

In July, the Biden administration took steps to address the mounting problem, introducing an OSHA enforcement initiative on extreme heat that would ramp up workplace inspections in high heat areas and issue hazard alerts to employers. Phoenix airport workers hope their complaint will push the agency to rigorously enforce these regulations.

In the complaint, workers also reported a lack of adequate medical attention for workers experiecing obvious heat illness. “The time that I suffered from extreme fatigue weakness I told my supervisor,” Linda Ressler, a cabin cleaner, reported in the written complaint. “She told me that I can either go home or she can get me an ambulance. I didn’t want to get the ambulance, because I don’t have money to pay. I was also in and out of conscious[ness] and was confused and didn’t know what to do.”

Workers like baggage handlers and runway signalers who direct aircraft on the tarmac are obviously most at risk from dangerous heat exposure. But cabin cleaners can experience stifling conditions when plane engines and air conditioning are turned off during layovers and the jet feels like a superheated aluminum can.

“They definitely are the invisible people,” Van de Kerk said. “Passengers don’t see them.”

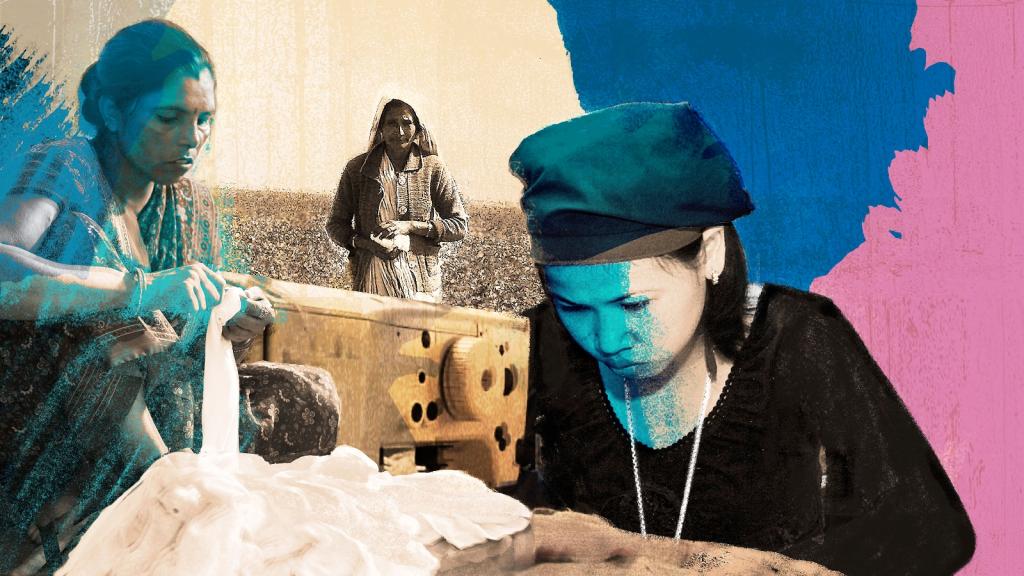

According to Service Employees International Union, inflation-adjusted wages for airport service workers have not risen in 20 years. Unlike flight attendants, these employees are not often unionized, instead contracted by the airline to work in a specific terminal, despite the fact that the airline controls the conditions of their workplace. These folks also are disproportionately people of color, and many are immigrants.

Van de Kerk, for example, is not an official employee of the Phoenix airport or any specific airline. She is a contract worker for Prospect Airport Services. Arizona is a low-bid state, so the airport hired the company that required the least amount of money. Employees earn minimum wage. And the company, as a third party, doesn’t fall under most basic protections for workers. “Contract workers have nothing,” Van de Kerk said. “We have no voice.”

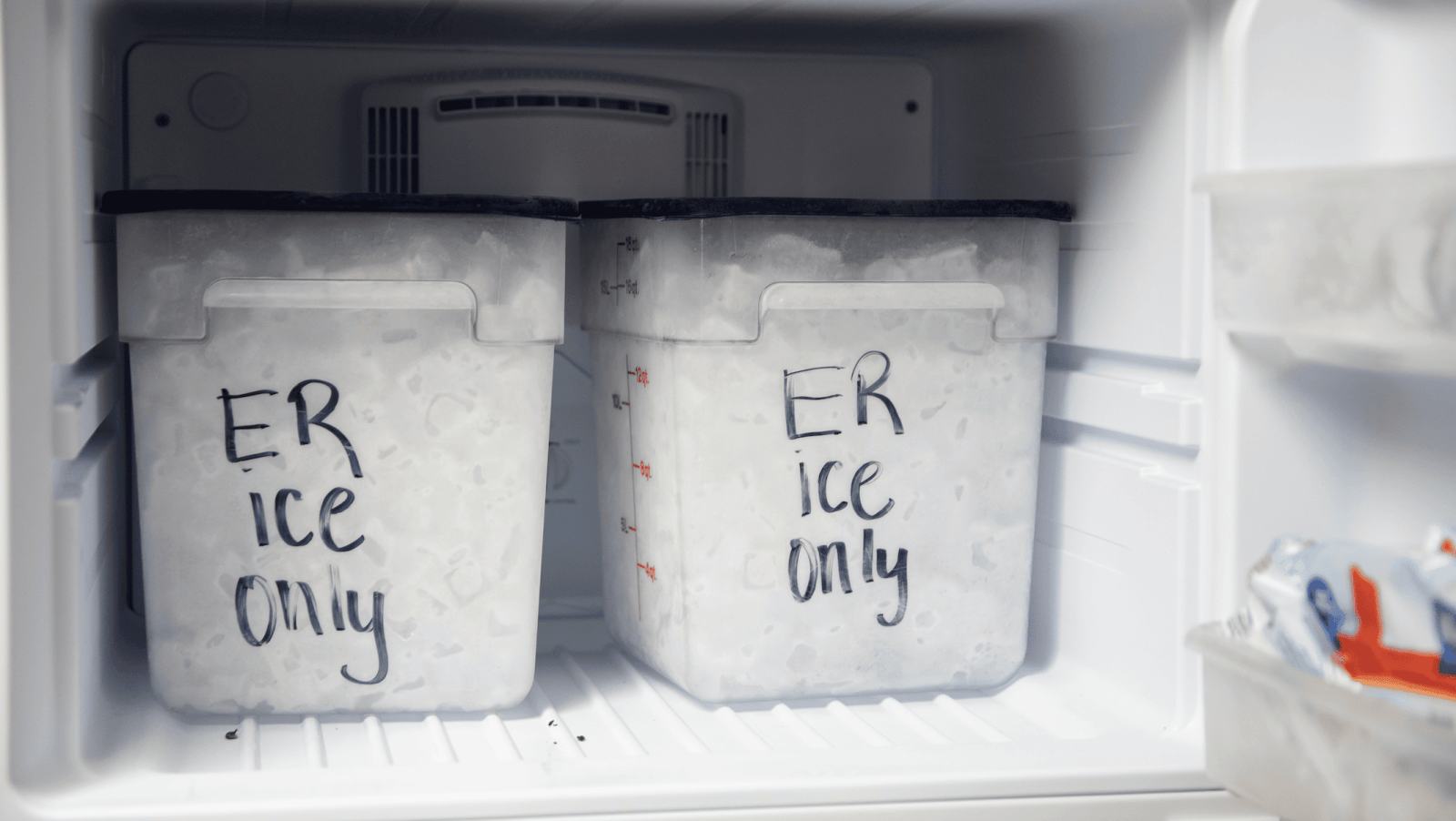

Phoenix has been so hot this summer that people have received third-degree burns from touching asphalt. Local emergency rooms have been inundated with patients exhibiting signs of heat-related illnesses. At the airport, cabin cleaners describe drinking water from the bottles passengers leave behind just to stay cool as the cabins they worked in reached unimaginable temperatures.

Prospect Airport Services did not respond to a request for comment.

Advocates say there is a chance to change things within the airline industry soon. The Federal Aviation Administration’s reauthorization deadline is less than a month away. Labor unions consider it a chance for Congress to require better wages and sick leave for airport service workers. If argued right, that could also include developing safety protocols for workers in dangerously hot conditions.