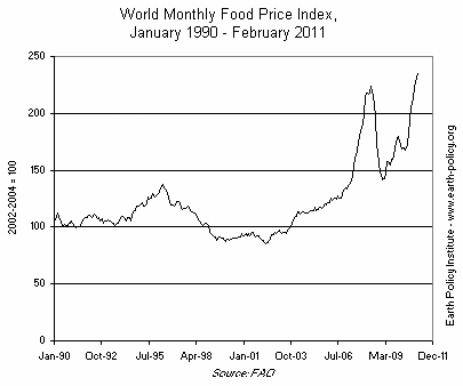

Click for a larger version.In February, world food prices reached the highest level on record. Soaring food prices are already a source of spreading hunger and political unrest, and it appears likely that they will climb further in the months ahead.

Click for a larger version.In February, world food prices reached the highest level on record. Soaring food prices are already a source of spreading hunger and political unrest, and it appears likely that they will climb further in the months ahead.

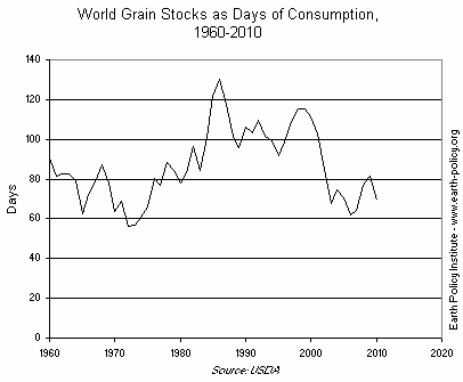

As a result of an extraordinarily tight grain situation, this year’s harvest will be one of the most closely watched in years. Last year, the world produced 2,180 million tons of grain. It consumed 2,240 million tons, a consumption excess that was made possible by drawing down stocks by 60 million tons. To avoid repeating last year’s shortfall and to cover this year’s estimated 40-million-ton growth in demand, this year’s world grain harvest needs to increase by at least 100 million tons. Yet that would only maintain the current precarious balance between supply and demand.

Click for a larger version.To get prices back down to a more acceptable level, it would take perhaps another 50 million tons for a total increase of 150 million tons. Can the world boost this year’s grain harvest by 150 million tons or even 100 million tons? It is possible, because we have had annual harvest jumps of 150 million tons twice over the last two decades, but this year it does not appear likely.

Click for a larger version.To get prices back down to a more acceptable level, it would take perhaps another 50 million tons for a total increase of 150 million tons. Can the world boost this year’s grain harvest by 150 million tons or even 100 million tons? It is possible, because we have had annual harvest jumps of 150 million tons twice over the last two decades, but this year it does not appear likely.

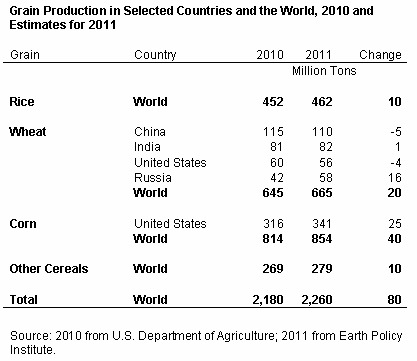

In assessing the world grain harvest prospect, we focus on the big three grains — rice, wheat, and corn — that together account for nearly 90 percent of the harvest. Barley, oats, sorghum, rye, and millet make up the remainder.

We start by looking at rice because, as an irrigated crop, its production fluctuates little. The average annual gain in the world rice harvest, which totaled 452 million tons last year, has been 7 million tons. Let’s assume that we get a 10 million ton gain in rice this year.

Wheat, now the world’s leading food grain, is much more difficult to assess because so much of the harvest is rain-fed, making yields as variable as the rainfall. But since most wheat is winter wheat, which is planted in the fall, is dormant in winter, and resumes growth in early spring, we know that this year the wheat area planted is up by 3 percent. We also have an early sense of the crop’s condition.

We begin with the big four wheat producers — China, India, the United States, and Russia — which collectively produce half the world’s wheat. China, the leading wheat producer, was until very recently suffering the worst drought in its winter wheat-growing region in 60 years. Although rain and snow in late February and early March rains and snow have lessened the drought effect, we could easily see China’s wheat harvest drop from 115 million tons last year to 110 million tons this year. India officially expects an 82-million-ton harvest, up 1 million tons from last year.

In the United States — the third ranking wheat producer — the southern Great Plains are suffering from drought. As of the end of February, the U.S. winter wheat crop condition was among the worst in the last 20 years. The U.S. Department of Agriculture estimates the harvest will drop from 60 million tons to 56 million, and this may be conservative.

Russia’s wheat harvest should be up sharply from last year’s heat-devastated crop of 42 million tons. But last fall it was too dry to plant one fifth of its winter wheat, which means many more farmers will plant lower-yielding spring wheat — wheat that is planted in the spring and is harvested in the late summer or early fall. With a little luck, Russia should harvest roughly 58 million tons of wheat.

Adding in the rest of the world’s expected wheat production, can we match last year’s world wheat harvest figure of 645 million tons? We should exceed it. The International Grains Council estimates this year’s harvest at 672 million tons, up by 27 million tons over 2010. This contrasts with the Canadian Wheat Board estimate of 653 million tons, a gain of only 8 million tons. For calculation purposes, let us assume that this year’s wheat harvest is up by 20 million tons for a total of 665 million tons.

Now for corn. Two countries tell the story here: the United States and China, which produce 40 and 20 percent, respectively, of the 814-million-ton world corn harvest. Combining the expected 4 percent increase in U.S. planted area with a 10-ton-per-hectare yield, the U.S. corn harvest could increase by 25 million tons. China’s corn harvest, which has fluctuated around 165 million tons for the last three years, is not likely to increase given its tight water situation. For the remaining 40 percent of the corn harvest, we will assume a gain of 15 million tons. All together this takes the world harvest up by 40 million tons.

Let’s review the global numbers. It will take 100 million tons of additional grain just to maintain the current precarious situation and close to 150 million tons to restore some semblance of stability in the world grain market. We can count on a 10-million-ton increase in this year’s rice harvest. We are hoping for a 20-million-ton rise with wheat and a 40-million-ton jump in corn. Let us also assume that minor cereals increase by 10 million tons over last year. This would give us a total increase of 80 million tons, not enough to prevent further price rises.

Click for a larger version.Estimating world grain production is becoming more complex and difficult. On the demand side of the equation, there are three sources of growth: the addition of 80 million people per year, some 3 billion people moving up the food chain consuming more grain-intensive livestock products, and the massive conversion of grain to fuel ethanol in the United States.

Click for a larger version.Estimating world grain production is becoming more complex and difficult. On the demand side of the equation, there are three sources of growth: the addition of 80 million people per year, some 3 billion people moving up the food chain consuming more grain-intensive livestock products, and the massive conversion of grain to fuel ethanol in the United States.

On the supply side, there was a time when grain production was on the rise almost everywhere. That world is now history. In a number of countries, grain harvests are shrinking because of aquifer depletion and severe soil erosion. Rising temperatures are also taking a toll. And some agriculturally advanced countries have run out of new technology to raise land productivity.

In 18 countries containing half the world’s people, overpumping for irrigation is depleting aquifers. Among the countries where harvests are falling as aquifers are depleted are Saudi Arabia, Syria, and Iraq. World Bank data for India indicate that 175 million people are being fed with grain produced by overpumping, which by definition is a short-term phenomenon. The comparable number for China is 130 million people.

In some countries such as Mongolia and Lesotho, grain production has fallen by half or more in recent decades as severe soil erosion has led to wholesale cropland abandonment. In North Korea and Haiti, soil erosion is undermining efforts to raise output.

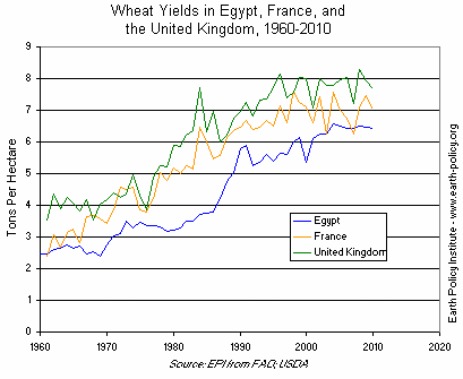

In several agriculturally advanced countries, the backlog of unused technology has largely disappeared. Japan’s rice yield per acre has not increased for 16 years. China’s rice yield, now approaching that in Japan, may also be about to level off.

Click for a larger version.In France, Europe’s leading wheat producer, yields have been flat for a decade. Wheat yields have also plateaued in Germany and the United Kingdom. In Egypt, Africa’s leading wheat producer, wheat yields have been flat for six years.

Click for a larger version.In France, Europe’s leading wheat producer, yields have been flat for a decade. Wheat yields have also plateaued in Germany and the United Kingdom. In Egypt, Africa’s leading wheat producer, wheat yields have been flat for six years.

At this point, it seems unlikely that we will get the 100-million-ton grain harvest increase this year that would be needed just to maintain the current rather precarious situation. Instead, it looks more likely that we will reduce stocks further. It may be somehow possible to avoid a rise in world food prices in the months ahead, but at this point it seems unlikely.