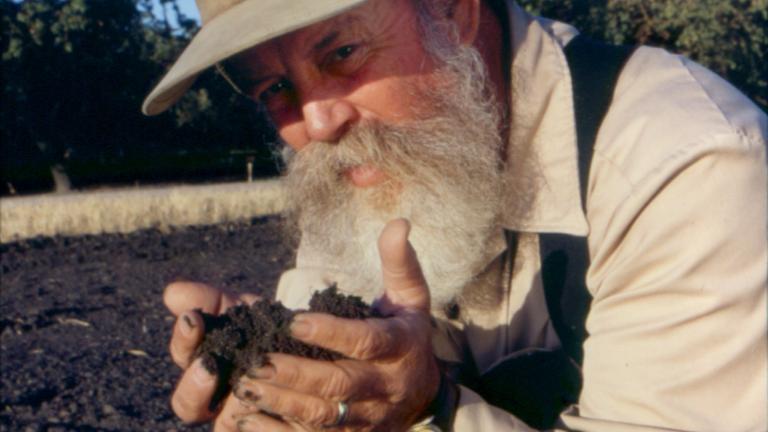

David Mattheson PhotographyBu Nygrens, director of purchasing for Veritable Vegetable.

This is part of a series in which we’re asking what pragmatic steps we can take to make regional food systems more sustainable. Last time we spoke with organic farmer Tom Willey.

A few years ago, I bought a little share in a dairy farm so I could receive my own portion of creamy Jersey milk. Each week I’d fish a heavy Mason jar out from under a blanket of tinkling ice cubes. It was delicious, and when it went off it only got better: mixed with scalloped potatoes, salt, and onions, the fermenting milk transformed in the oven into cheesy ambrosia.

But there was a big problem with this milk: It waited for me on the other side of town. It took me a little over an hour to fetch it by car. I know because I didn’t have a car at the time, and so I’d rent a Zipcar and try to run the errand in under an hour. Then the farm started asking for members to drive out regularly to do chores. That was too much for me. I bailed out and went back to buying milk at Safeway.

The experience taught me to appreciate the middleman — someone who, for a reasonable fee, handles the logistics and transportation. Middlemen get a lot of grief. There are thousands of ads that exhort you to “cut out the middleman!” From the outside, the middleman just looks like a barrier between the consumer and low wholesale prices. But for small food producers, having a middleman can dramatically expand the number of eaters who can buy their stuff.

Middlemen might also help farmers fill the missing middle of our food system. Right now we have big farms that move their food to market with industrial efficiency, and we have little farms that rely on dedicated eaters to drive out over the potholes, but we don’t have much in between. In part, that’s because those companies that efficiently move trainloads of grain to market think making a trip to pick up a dozen pounds of salad greens is, ahem, just radicchio.

For the past few years, people have been saying that there’s a solution to this problem: food hubs. Food hubs are essentially big warehouses — with a fleet of trucks and a staff of marketing and logistics gurus, who can connect farmers to restaurants, stores, and school lunch programs.

The USDA has supported the idea, and now recognizes 227 food hubs operating around the country. Last fall, Rowan Jacobson checked the vital statistics on the food hub concept in a piece for Orion Magazine. He found that, while some were thriving, many food hubs couldn’t make ends meet:

“Almost all food hubs that meet the dictionary definition are not profitable,” says Amanda Oborne, who directs the conservation organization Ecotrust’s FoodHub, an online dating service for wholesale food buyers and sellers. How could they be? They are competing in one of the world’s most cutthroat businesses, which often operates on net margins of less than 1 percent, and they are trying to return more money to the farmers, operate on smaller scales, and provide additional social and environmental services.

When I started scanning the list of food hubs, one name jumped out at me: Veritable Vegetable. I’d seen this company’s trucks long before I’d ever heard the term “food hub.” This meant, presumably, that Veritable had figured out how to make a food hub work long before the hype and the funders started making it trendy.

When I visited one of the company’s warehouses — in an industrial section of San Francisco — co-owner Bu Nygrens confirmed my assumption.

“It seemed like an artificial term, that both foundations and government were fueling, for something that we’d been doing for 40 years,” Nygrens said.

David Mattheson Photography

Veritable Vegetable started in 1974. “It grew out of the leftist politics about economic equality, and the natural food industry’s demand for brown rice and tofu and crunchy granola and all that stuff,” Nygrens said.

Moving all that food required trucks, and refrigerators, and organizers. There’s nothing bucolic about this sort of thing. When I visited Veritable, I found myself in a warehouse filled with forklifts, pallets, and boxes. Everything beautiful and pastoral was hidden away inside those boxes. Nicole Mason, the community involvement manager, showed me from one refrigerated room to another. To see what’s remarkable about Veritable you have to look closely: You have to notice that, for many farms, the produce isn’t coming by the truckload, or even the pallet, but just a few boxes at a time.

In the years since 1974, Veritable has proven that the business of picking up just a few boxes of produce from farmers can be profitable. Big distributors probably could have provided the same service, but they had no incentive to take on the challenge. There’s a kind of inertia that develops with success. Why change things when you’re already making money?

That inertia provided a niche for Veritable, but it’s also been a frustration. For instance, the company couldn’t convince any truck manufacturers that it would be worthwhile to build fuel-efficient hybrid semis.

“We wanted hybrid trucks 10 years ago and the tech wasn’t there,” Nygrens said. “It was only when Coca-Cola demanded a green fleet that [the truck company] Kenworth came up with the equipment, and then we could get the equipment.”

Within four years, savings on fuel more than paid for the new trucks (it was more like two when you count the money from tax credits). But even though these changes made economic sense, not everyone is making them: Veritable stands out from the crowd. In 2012 a trucking trade magazine recognized the company for having the “green fleet of the year.” There are lots of smart, obvious changes like this that big food companies could make, Nygrens said, but change is hard: “They are very slow to react. They are behemoths. It’s hard to move them.”

So what are the next steps to move forward with more sustainable food? Despite her initial reaction, Nygrens says that more food hubs, and more people thinking hard about how to connect farmers with eaters, can only help. In the end, she said, the buzz is good because it gives the middlemen a little of the glory. “There’s not a lot of romance in moving boxes of food around,” she said.

Mason nodded. “Distribution might be the least sexy part of the food system,” she said. “One of the challenges is attracting and retaining the most talented people.”

So the people at Veritable welcome the theoreticians preaching about food hubs, and the techies working on farm-to-table apps.

Another challenge, Nygrens said, is educating eaters. For instance, Veritable found that people just wouldn’t buy dirty carrots — they looked bad, even if they were better quality. And farmers couldn’t afford to buy carrot washers. In the end, Veritable decided it had to get the bulk of its carrots from the bigger farms, that could wash their carrots. If eaters are willing to budge on this sort of thing, and learn when great flavors are hidden behind aesthetic imperfections, it would be a huge boon to farmers, Nygrens said.

She’d recently heard an apple farmer from New Hampshire named Michael Simmons wax lyrical on weird-looking fruit: “He said, a blemish on an apple indicated that the tree was healthier because it was able to withstand the attack. So people should be educated that the fruit itself was heartier, healthier, with more nutritional density perhaps, and I was like, wow! I mean, I’ve been in ag for a long time and I never … yeah!”

At the same time, there’s an opportunity for farmers and their allies to invent cheap technical solutions to these problems. Perhaps there’s an inexpensive way to wash carrots, or a way of cooperating to share equipment.

At the end of the interview, I told Nygrens and Mason about my misadventures with the milkshare. It was a hassle, I said, but sometimes the hassle was part of a richer experience. For instance, I organized with a couple people who lived nearby to take turns picking up the milk. It was a logistical tangle, but it also allowed for some human connection that wouldn’t have happened otherwise. That led to the formation of friendship that I truly value.

In return Nygrens offered a similar story, about a community supported agriculture farm that worked with Veritable to deliver produce. It wasn’t an efficient system: The farm packed up the food in bulk, and families came to the warehouse to pick it up. “The kids would be running around the warehouse, it was just like a little mini festival, and I loved that they would take all the food even if it had a little bug damage or something. We need more of that.”

On the one hand we want to make this as easy as possible, to allow people with less money and time to participate and get good food; but on the other hand, if you just reduce everything to time and cost, something is lost.

Food hubs promise to reduce transaction costs and bring good food to more people. But sometimes the costly transactions themselves are what make alternative food systems special, Nygrens said. The people behind Veritable Vegetable spend a lot of time thinking about how to strike that balance.