Frank Bibeau remembers canoeing on the waters of northern Minnesota with his father on a late summer day in 1996. The sky and placid lake stretched to the horizon all around their red canoe, interrupted only by stalks of delicate grasses protruding through the lake’s surface. Bibeau navigated with a long pole while his father, perched in front, rhythmically knocked grains from the stalks into the boat, harvesting wild rice.

Every year, from the time the maple trees first mottle gold and red in late summer until the first frost, Anishinaabe all across the Great Lakes region embark on the wild rice harvest. Bibeau learned to harvest the grain from his father, who learned from his father before him, and so on — “since time immemorial,” he told me.

For Bibeau and the Anishinaabe people, the wild rice harvest is at once tradition, sustenance, and cultural lifeway. According to their oral tradition, the Anishinaabe came to settle in the Great Lakes basin thousands of years ago when they followed a sacred shell in the sky to a place where food grew on water. When they arrived, they found wild rice — one of the only grains native to North America. Wild rice in the Anishinaabe language is manoomin: the good berry.

“Wild rice is our life. Where there’s Anishinaabe there’s rice. Where there’s rice there’s Anishinaabe. It’s our most sacred food,” said Anishinaabe activist Winona LaDuke. “It’s who we are.”

The future of wild rice in this region, however, is at risk. Wild rice has already been threatened by climate change, mining, water pollution, and genetic modification. LaDuke runs the White Earth Land Recovery project, a nonprofit that seeks to preserve the wild rice harvest, as well as the environmental justice nonprofit Honor the Earth. She’s spent much of her career defending the grain. “We have very little left, and it’s central to our identity,” she told me.

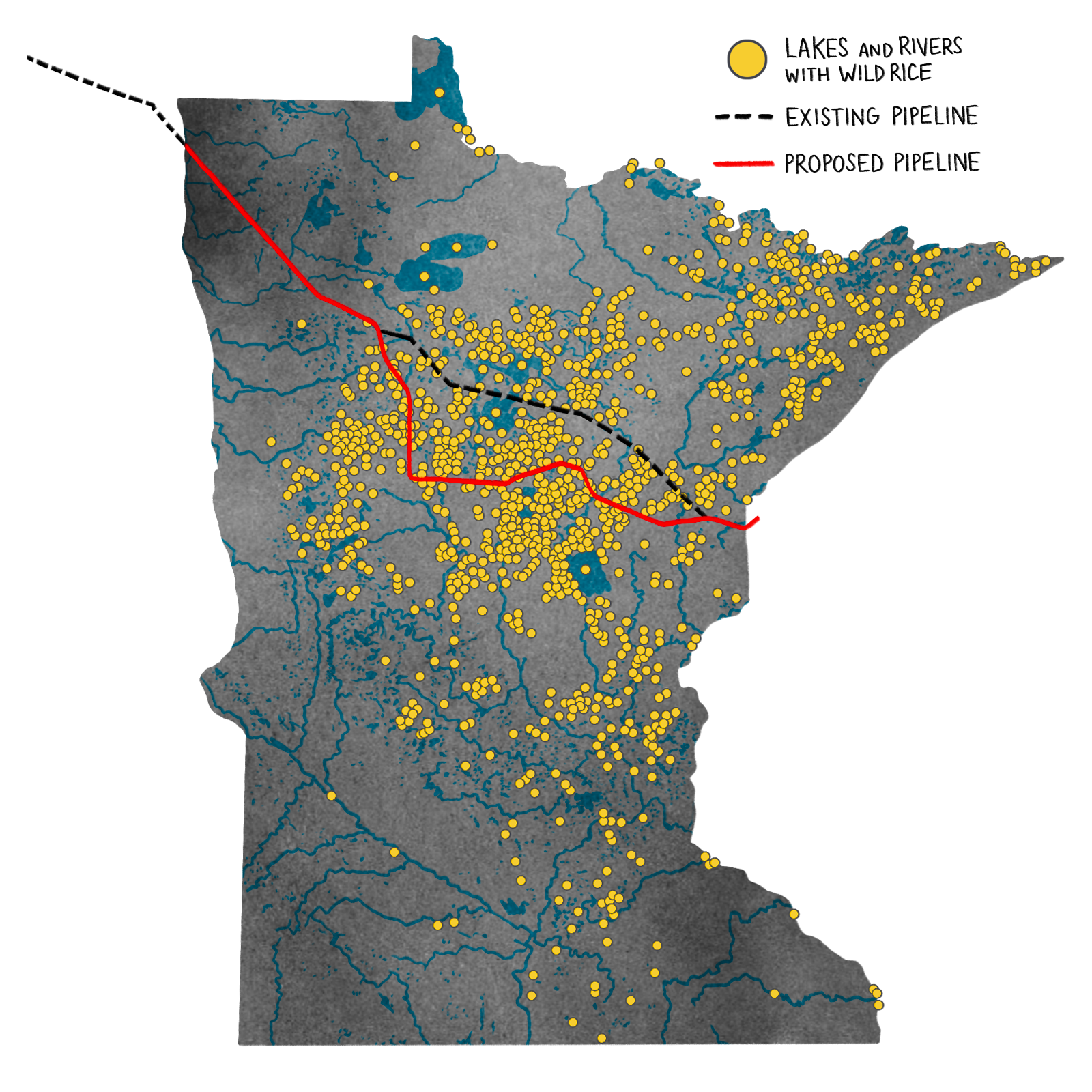

Now, LaDuke and Bibeau are facing a new battle for the future of wild rice: the so-called Line 3 pipeline, which is slated to carry 760,000 barrels of crude oil a day across more than 200 bodies of water, including lakes, streams, wetlands, the headwaters of the Mississippi River — and over 3,400 acres of wild rice waters.

On Monday, thousands of protesters from across the country gathered along the pipeline’s new route in the forests of northern Minnesota. They marched to the headwaters of the Mississippi River — which the pipeline will cross underground in two locations — for a ceremony and later moved to a construction site, where some blocked the road with an old fishing boat and others chained themselves to equipment. More than 100 people were arrested; police used a long-range acoustic device as a sonic weapon against the crowd. U.S. Customs and Border Protection dispatched a helicopter that hovered 20 to 25 feet over a group of protesters occupying a pump station, kicking up massive clouds of dust and debris.

This is not Line 3’s first incarnation. Originally built in the 1960s by the Canadian company Enbridge, the pipeline carries oil over 1,000 miles from Alberta’s tar sands through Minnesota to Superior, Wisconsin. In 2014, Enbridge applied for federal and state permitting to replace the existing pipeline, citing concerns over aging infrastructure, including the possibility of an impending spill. The project was classified as a replacement for the purposes of permitting, even though much of the pipeline’s Minnesota portion is being constructed along an entirely new route.

The possibility of oil spills on the new pipeline route looms over the wild rice waters it crosses. Enbridge is no stranger to spills: From 2002 to 2018, the pipeline network owned by Enbridge caused 291 crude oil spills in the U.S, a total of over 2.7 million gallons. The old Line 3 itself has a history of spills in the region; in 1991, a section of Line 3 ruptured near Grand Rapids, Minnesota, causing over 1.7 million gallons of oil to spill into a tributary of the Mississippi River. It was the largest inland oil spill ever recorded in the U.S., but luckily it occurred in winter, when the river was frozen over with 18 inches of ice, allowing for a relatively straightforward cleanup. That was not the case in Marshall, Michigan, when another Enbridge pipeline ruptured in 2010, spilling 840,000 gallons of oil into the Kalamazoo River, resulting in $1.2 billion in cleanup costs and contamination of the riverbed and its ecosystems with bitumen, which may never fully be remediated.

The spill on the Kalamazoo was particularly damaging because that pipeline, like Line 3, carried oil from the Alberta tar sands. In addition to being an especially powerful accelerator of climate change — the oil produces emissions 14 percent higher than the average oil used in the U.S. — tar sands oil is composed of a heavy crude known as diluted bitumen, or dilbit. When spilled, the diluent evaporates, causing health risks when inhaled, and leaves behind bitumen, a dense tar. Bitumen doesn’t float on the surface of the water like lighter crudes. Instead it sinks, mixing and adhering to sediments and plants, making it particularly costly and difficult to clean. The spill hit the surrounding community hard; in its aftermath, 150 families moved away from the area permanently. Enbridge estimates that a worst-case scenario spill from the new Line 3 would cost even more than the Kalamazoo spill, reaching $1.4 billion in cleanup costs.

“Line 3 is a safety-driven project, replacing an aging pipeline with state-of-the-art energy infrastructure to serve the region’s energy needs,” an Enbridge representative wrote to Grist in an email. “Impacts on threatened and endangered species are taken into consideration and are mitigated in permit conditions imposed on the project by government agencies along with our own construction plans.”

Wild rice is what’s known as an indicator species — meaning it tends to reflect the overall health of an ecosystem — and it requires abundant, clean water in order to grow. The crop is therefore especially vulnerable to oil spills. The new Line 3 is set to pass through the heart of Minnesota’s wild rice lakes — some of the best remainingwild rice waters in the world.

Since its proposal, the pipeline has faced an embattled decade, including several rounds of legal challenges from Indigenous communities, environmental groups, and the Minnesota Department of Commerce. But Enbridge and its lawyers have consistently beaten back those challenges. In November, the Army Corps of Engineers approved the pipeline’s federal permit to build over the bodies of water along its new route, and shortly afterwards the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency granted the final permit that the pipeline needed to move forward. Construction on the project in Minnesota began in December.

The water crossing permit issued by the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, or MPCA, states that Enbridge cannot build the pipeline within 25 miles upstream of wild rice waters, but scientists who commented at the permit hearing argued that their warnings about the potential environmental impacts of oil spills and climate change were ignored, and that they only had the opportunity to give input at the end of the permit approval process. After the permit was approved, 12 of the 17 members of the pollution control agency’s environmental justice advisory board resigned, stating that they could not “continue to legitimize and provide cover for the MPCA’s war on Black and brown people.” They argued that the agency’s approval of the permit despite the advisory board’s opposition to the project was proof that the board’s recommendations were not being heeded.

Now that construction has started, protest camps have developed in response to the pipeline, and attention has turned to the Biden administration, which canceled the controversial Keystone XL pipeline during its first days in office. Indigneous leaders like LaDuke and Minnesota politicians like U.S. Representative Ilhan Omar have written letters calling on President Biden to take similar action on Line 3. “You can’t cancel Keystone and then build an almost identical tar sands pipeline,” tribal attorney Tara Houska told Biden administration advisers last month. (Editor’s note: Houska was selected as Grist 50 Fixer in 2017.) The president hasn’t yet commented on his administration’s position on the future of the pipeline.

LaDuke has been fighting the pipeline in court and at regulatory hearings since the beginning. “Seven years of my life I’ve spent on this,” she told Grist, “I’ve testified at so many hearings. Then they kept asking us to testify again. How many times do you ask your people to come out and cry for a judge?”

I met Bibeau on a cool September day at a facility on the Leech Lake Reservation where he processes wild rice each fall. He was dressed in camo and greeted me with an easy, toothy smile. The earthy smell of wild rice husks and steady thrum of an old engine filled the air of the shed where he runs the processing equipment. A few non-Native men had traveled to the reservation at Bibeau’s invitation to either assist or learn about wild rice processing.

“It’s something to be proud of,” he told me, watching the men load grains from one machine to the other. “How deep into the culture can you be, helping people to prepare food?”

The men dried the freshly harvested wild rice over a wood-burning fire until the husks came off easily when ground. Then, they loaded the grains into a thrasher, which spun the rice around, breaking up the hull. Finally, they poured the grain into a third machine that spat out the chaff. Bibeau oversaw the process from the side, leaning on two canes (his hips were causing him trouble) and giving instructions. “The best part is the smell,” Bibeau told me, grinning at the scent of toasted grain and campfire. All of this processing was once done by hand; now, Bibeau and many other wild rice processors use machines to speed up the job. “All these machines replace Indians,” joked Bibeau, “and we’re OK with that.”

Bibeau, who is a lawyer for Honor the Earth, has been fighting Line 3 in the courts for years, and he sees a unique opportunity in the legal battle. Bibeau understands Line 3 as another chapter in the state of Minnesota’s long history of ignoring Indigenous treaty rights and argues that the case may be an opportunity to force the state to recognize those rights.

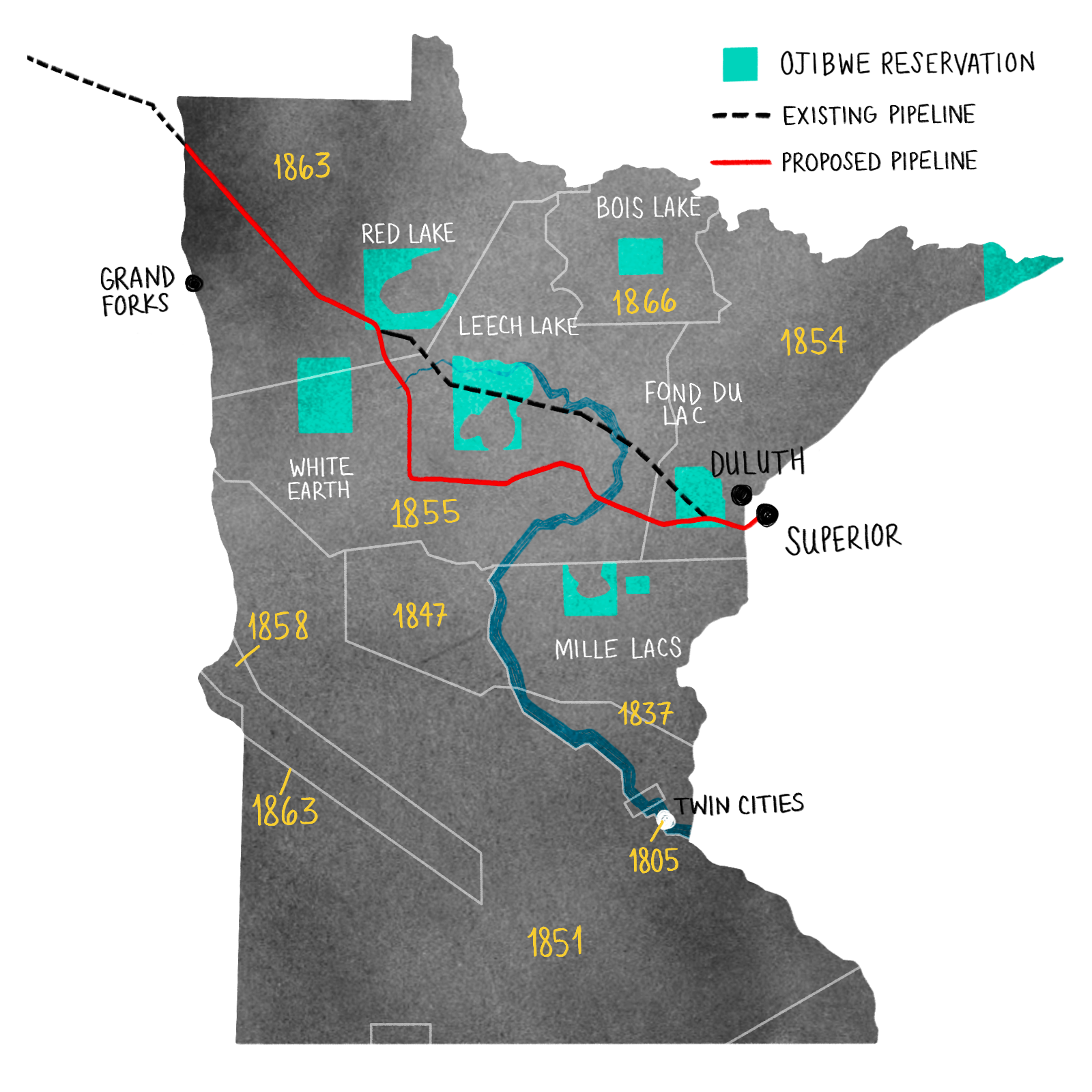

The land that is now called Minnesota was signed over to the U.S. government in a series of treaties spanning three decades in the mid-1800s. Before that, the Anishinaabe — and more specifically the Ojibwe — arrived in the land of wild rice at the end of a long westward migration. When the fur trade arrived in the 1600s, the Anishinaabe operated as trappers, trading with the British and French. In this position, the Anishinaabe grew their political power and territory for two centuries, expanding into the lands of present-day North Dakota, Montana, Ontario, and Saskatchewan.

In present-day Minnesota, the Anishinaabe people’s first large land concession was an 1837 treaty that coincided with the decline of the fur trade. U.S. fur interests used their political connections to engineer treaties in which the federal government purchased titles to Indigenous land with cash that tribes could use to pay debts claimed by fur interests. “Title to the land was an alien concept to the Ojibwe,” the Anishinaabe scholar Anton Treuer has written. “Cash payment for title seemed a great deal as long as the Anishinaabe didn’t lose the right to use the land.”

The Anishinaabe negotiators of the treaty, therefore, made certain that the Anishinaabe retained use rights to the land ceded by the treaty for hunting, fishing, and gathering of wild rice. “You know we can not live, deprived of our lakes and rivers,” the Anishinaabe Chief Eshkibagikoonzh said during the treaty negotiations. “We wish to remain upon them, to get a living.” These use rights were thus written specifically into article 5 of the 1837 treaty, and they were reaffirmed in a 1999 U.S. Supreme Court decision that also applied those rights to lands ceded in subsequent treaties — including those through which Line 3 is set to run.

Bibeau sees the appearance of the words “wild rice” in the 1837 treaty as a crucial part of the fight against Line 3. Because the risk of oil spills threatens water quality, Bibeau argues that the pipeline construction interferes with the use rights guaranteed by these treaties. “When you look at wild rice, maple syrup, and fish, they all require abundant, high quality water,” said Bibeau. “I see that our rights are linked to abundant, high quality water that can’t be risked anymore for new pipeline corridors.”

“Enbridge has demonstrated ongoing respect for tribal sovereignty,” a company representative countered in an email to Grist, pointing to officials from the Leech Lake and Fond Du Lac reservations who have expressed support for the project’s permits. “The project is now being built under the supervision of tribal monitors with authority to stop construction, who ensure that important cultural resources are protected.”

Honor the Earth and the White Earth Band of Ojibwe have filed multiple rounds of legal challenges to Line 3 based on these treaty rights, including challenges to the assessment of the project’s environmental impacts and the permit approving the pipeline’s new route, which were approved by the Minnesota Public Utilities Commission, as well as to the water crossing permit granted by the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency in November.

Most recently, in December of 2020, the nonprofit environmental law organization Earthjustice filed a federal lawsuit against the Army Corps of Engineers on behalf of the Red Lake and White Earth nations and Honor the Earth, arguing that the permit is unlawful because the Army Corps didn’t conduct its own environmental impacts statement as required under the 1970 National Environmental Policy Act. The plaintiffs argue that the original analysis violated treaty rights by not adequately considering the environmental impacts of the pipeline on treaty waters.

Bibeau compared the legal argument against Line 3 to a seminal treaty rights precedent set by a 2018 Supreme Court case. The court ordered the state of Washington to remove culverts (tunnels that provide drainage under roadways) because they had a negative effect on the salmon population, a food protected by treaty language. The court ruled that the state could not uphold its treaty obligations while the culverts degraded salmon habitats. And just as the culverts degraded salmon habitats, says Bibeau, so would Line 3 degrade wild rice waters.

Bibeau anticipates that further legal action could be filed against the state of Minnesota over Line 3 in the federal courts — and that the treaty rights arguments will hold more weight in these courts than the Minnesota courts. “There’s other cases we’ve worked through in the last decade that have shown us just how powerful our treaty rights are. The problem is, I can show you the same amount of cases over the last five years where the state of Minnesota says, ‘We don’t give a crap about what you think your treaty rights are,’” said Bibeau. “Every time Line 3 gets closer to happening, it pushes our treaty rights closer to the front, and now we’ve gotten to that place with the litigation starting with the Corps of Engineers.”

Bibeau believes that the water rights held by the tribes are strong enough that the state of Minnesota doesn’t have the right to build Line 3 across sensitive waters without the consent of the tribes. For Bibeau, the pipeline fight is a broader opportunity for gaining recognition of the need for prior informed consent — the importance of asking tribes if they support the construction of a major infrastructure project like Line 3 — when it comes to water rights. “I’d like to think we can ride Enbridge like a pig with lipstick towards our treaty rights goal,” said Bibeau.

“If we have water rights, which I believe we do, then you need our consent to even cross the waters or use the waters for another purpose that we think is harmful. When we get to that consent place, it’s going to change the dynamics across the nation.”

Bibeau sent me off with a piece of smoked fish and a trunk full of processed wild rice, with instructions to deliver it 100 miles west, to LaDuke’s home on the White Earth Reservation. It was there that I met Tim, an activist and enrolled member of the Standing Rock nation who requested his last name be withheld from publication. LaDuke prepared a cauliflower-crust pizza, leaving Tim and me to sit on her back deck, overlooking her small vegetable garden.

Tim came to the Line 3 fight by way of the battle over the Dakota Access pipeline, or DAPL. He had camped at the DAPL protest site for nine months, and his experiences there made him determined to get ahead of the next fight. “I wanted to come out here and have a head start,” he told me, “not like at Standing Rock, where by the time that anybody really paid attention it was half constructed.” Tim’s grandmother was a member of the White Earth band of Ojibwe, and when he left Standing Rock, he started camping on his family’s ancestral land on White Earth Reservation after hearing about the new pipeline that was coming to the region. He’s been there now for three years. He scouts the entire pipeline route from Wisconsin to the North Dakota border regularly, and he watched from public land as Enbridge built storage yards and access roads. A few others came with him initially from DAPL, but as the years went on the numbers dwindled.

But now, as construction moves forward, protest actions have resurged, with activists locking themselves to equipment and protesting along the pipeline route. Protesters are being met with a policing force that has been preparing for this exact scenario for years as the permitting process simmered in the background. Reporting from The Intercept has found that local police departments and private security contractors have been monitoring Indigenous activists, including LaDuke, online and off under the umbrella of a multi-agency initiative called the “Northern Lights Task Force.” In late 2017, members of the Cass County Sheriff’s office, which played a role in coordinating the police response to DAPL at Standing Rock, gave presentations to police officers in Minnesota on lessons and tactics from their crackdown on DAPL protesters. In the fall of 2020, officers participated in a training exercise dubbed “Operation River Crossing,” simulating a confrontation with protesters along the pipeline route.

The surveillance of activists does not appear to have been limited to local police departments: U.S. Customs and Border Protection drones were also flown over the properties of anti-pipeline activists. (In response to a request for comment from Earther, which broke the story, Customs and Border Protection said that it “does not patrol pipeline routes,” even though the flight path in question was 90 miles from the border.)

Law enforcement hasn’t been the only group with their eyes on Line 3 protesters. Republican legislators in Minnesota have spent the past five years attempting to pass laws that would criminalize pipeline protest. State senator Paul Utke, the sponsor of a bill that would have made hiring or training anyone who in the future trespasses on pipeline property a felony punishable by a decade in prison and a $20,000 fine, even cited Line 3 as a reason for his sponsorship of the bill. “We saw what happened in North Dakota, and we have a big pipeline project coming up [in Minnesota],” Utke said of the bill in 2018.

Enbridge is also involved in the police response itself. In 2018, the Public Utilities Commission, or PUC, agreed to approve the pipeline under the condition that Enbridge would put together security plans for the pipeline route and create a Public Safety Escrow Trust Account with an initial fund of $250,000 to reimburse pipeline-related policing in counties along the route. The Beltrami County sheriff’s office has invoiced $190,000 in expenses to this account, including $72,000 worth of riot gear and over $10,000 worth of tear gas grenades, pepper spray, batons, and flash-bang devices. As of April 24, the escrow account has distributed $750,000 to law enforcement overall.

“To receive payment from the Public Safety Escrow Account, Local Government Units (LGUs) submit written, itemized requests to the Public Safety Escrow Account Manager, who was appointed by the Minnesota PUC,” an Enbridge representative wrote to Grist, emphasizing that the creation of the account was a requirement for the project to be permitted. “The Manager makes the determination on eligible expenses.”

LaDuke said in January 29 testimony before the Minnesota legislature that she’s seen a rise in security forces, including unmarked vehicles, since construction began. “There’s a lot of civil rights problems that are associated with a Canadian multinational paying the expenses of your police force in the state of Minnesota,” she said. Tim’s also seen the local police forces start to militarize. “They’re preparing way more in advance” for Line 3 than for Standing Rock, he said. “They’ve learned.”

As construction moves forward, pressure is increasing on the Biden administration to revoke the permit to cross water and wetlands that was issued by the Army Corps of Engineers. However, the administration’s recent decision not to take similar action regarding the Dakota Access pipeline doesn’t bode well for activists hoping that Biden will help stop Line 3. Meanwhile, Bibeau, Tim, LaDuke, and others are keeping up the fight in the courts and on the ground.

“I’m here fighting for Indigenous rights. Indigenous rights is my thing,” Tim explained as we sat eating cauliflower pizza on LaDuke’s back deck. “The land is sacred. The people are sacred. You can’t have the people without the land, and you can’t have the land without the people.”

He paused and looked out over the horizon, beyond the placid lake. “I know that if it was up to us, or up to any caretaker of the land, there wouldn’t be any of these pipelines.”

Bibeau, for his part, thinks about the red canoe that he gathered rice in with his father so many years ago. One day, he hopes to pass it down to a family member who will carry on the tradition. In the meantime, he bought a new canoe, on which he painted in big, blocky letters: “Love water not oil, stop Line 3.”