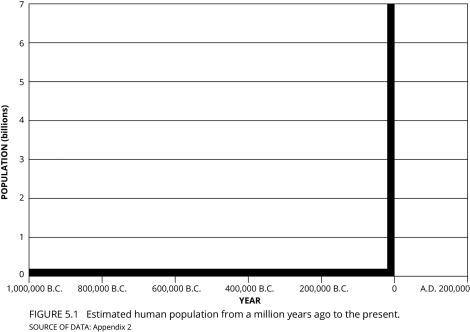

Zoom out on the graph of human population until it encompasses the entire timeline of our species and you’ll notice something alarming. It looks like a right angle, with one line hovering near zero for millennia, and another, at present day, headed straight up toward the stratosphere.

Here I sit, on a warm quiet day in my neighborhood, with children playing nearby and a train whistle farther off, living a reasonable, modest life. And yet, at the same time, I, along with you and the rest of us, am plastered against the tip of population rocket powering upward atop megatons of explosive fuel.

That graph comes from Joel Cohen’s 1995 book, How Many People Can the Earth Support? Though it’s now almost 20 years old, it’s still incredibly useful in exploring the conflicting answers to that question, because Cohen never takes sides. He simply (and exhaustively) lays out the arguments, and every shred of data used to support them.

Cohen is still alarmed by that graph. “We are in a completely unprecedented range of experience,” he said. He has a gentle, grandfatherly manner, and speaks slowly, choosing his words one by one. “Population has tripled in my lifetime. It’s changing the world so fast and in so many dimensions that people aren’t aware of the significance.”

Then he added, “But I don’t think we are powerless.”

When I wrote my last piece in this series, several people commented that I was off the mark in cheering rural development and looking for ways to enrich poor farmers. To paraphrase slightly, they asked: Shouldn’t we be fighting against the forces that build roads and electrical lines and bigger houses — rather than applauding them? In fact, isn’t saving poor children and ending hunger only going to make things worse as we ride out this population rocket headed who knows where?

It makes some intuitive sense to answer those questions with a “yes.” But intuition is a poor guide here. In reality, improving life for the poor is the key to ending population growth. All the evidence points the same way, Cohen said.

“If you want parents to make the choice to reduce their number of offspring, there’s no better way than making sure those offspring survive,” he said. “There’s no example of decline in fertility that has not been preceded by a decline in child mortality that I know of.”

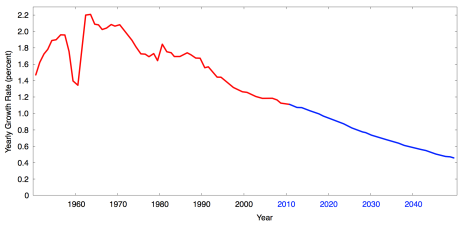

The doctor and statistics popularizer Hans Rosling can explain why this is in his usual, wonderful way. (Seriously, if you don’t know him, check out gapminder.org.) Basically it comes down to this: It makes economic sense to have lots of kids if you are poor. As people have become more prosperous, the population growth rate has been trending steadily downward.

Wikimedia CommonsWorld population growth rate 1950–2050.

Will things level out in time? No one knows. Though Cohen wrote the book on how many people the earth can support, he says, “the more I learned, the less I understood. It sounds like a simple question, but it’s not.”

But Cohen did come away with a useful way of framing the problem and the choices we can make to solve it. The problem is this: As population grows, and resources grow scarce, how do we divide up the global pie? The solutions we can choose among: bigger pie, fewer forks, and better table manners.

We can make the pie bigger through scientific advances — increasing farm yields and finding more efficient sources of energy. We can reduce the number of forks with family-planning programs, providing access to contraception and giving women more power over their bodies and finances. We can promote better table manners, that is, more equitable sharing, through, well, either more government or less. “The ‘better manners’ school calls for freer markets or socialism (depending on taste),” Cohen writes.

There’s tremendous controversy here, obviously, and not just on the last point. There are lots of people arguing that one of these solutions is paramount and the others are secondary. First we need better technology! No, first we need to reduce population! No, first we need revolution! But, Cohen says, “Almost 20 years later, I’m convinced that we cannot exclude any of those factors.”

After he finished the book, he held it for a year because he didn’t have a single overarching recommendation about what to do, and he felt he should. Then he went ahead and published anyway, without any prescription. A few years later, he had an idea: “Suppose we could educate all the worlds’ children, wouldn’t that help in all three dimensions?”

Education would allow children all over the world to become better farmers and scientists, and create appropriate technology for their needs. It would lead to lower birthrates, because when people get an education they tend to have smaller families. And an educated populace would be able to demand more from their governments. Cohen wrote two books as he pursued this line of thinking.

Then he changed his mind: Education alone wouldn’t work. “Educating all the world’s children would be a transformative change in human capacity, but you cannot educate a dead brain,” he said. In places where there is chronic malnutrition, children are stunted both mentally and physically. “It’s not going to happen until those children get fed, and those children aren’t going to get fed until their mothers get fed, because the effects start prenatally.”

And so he’s come back around to a three-pronged approach that mirrors his pie metaphor: more food for mothers and children, birth control, and education.

Joel Cohen

At the end of our conversation, when I asked Cohen if there was anything else he wanted to say, he thought for a moment, then delivered this miniature sermon:

“At the beginning of the 19th century, slavery was part and parcel of the economic system. Everyone took it for granted except a few nutcases. Today hunger, terrible, destructive hunger, is business as usual as part of the economic system, and it’s taken for granted. Slavery was wrong. Hunger is just as wrong. We have got to get rid of it. We need a change in consciousness so that it is no longer an acceptable part of our economic system. Unless we solve the hunger problem, we cannot solve the population growth problem.”

Wannabe Loraxes like me try to speak for the trees, which often means pushing back against the demands of humans. But in this case (unless you propose a truly evil route), what’s good for turtles, trees, and the larger ecological commonwealth is also what’s good for the poorest of our own species. If we want to solve this population problem, we need to become humanitarians.

Hat tip to Glenn Davis Stone, who suggested I read Cohen’s book. Grist has done a lot of good work on population — for more, check out this series.