This article is part of a mini-series on the plight of the mid-sized farm. Read part 1 on the difficulties of organic farming and part 3 on breaking the cycle of bigger farms and fewer farmers.

If I were still working the Smith family land, I’d be a fifth-generation Montana rancher. Instead, 628 miles, countless pairs of skinny jeans, and one internet job separate me from the family profession. Even after nearly a decade away, though, it doesn’t take much to take me back.

About a year ago, my boyfriend and I were clutching hands and whispering sweet nothings in a dive bar’s midnight air. When the jukebox switched to “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry,” the crowd and smell of stale beer faded away as I sat back, invisible hat in hand, to gaze at a hidden Montana horizon. My boyfriend glanced up from his beer to see his love-filled girlfriend transformed into a wistful, weatherbeaten Clint Eastwood squeezing back a horse-turd tear. “You’ve got to make me a mix of old country songs,” he said. “You don’t make mixtapes of songs like this,” Eastwood growled, squinting and drifting back to Hank Williams, Sr.

I’m gruff and conflicted when it comes to agriculture. While I love the farmers markets and food scene of Seattle, I miss our family cattle ranch, and the wheat farm my grandparents recently sold. I’ll dim the lights, massage my kale, and devour stories about food, but I feel a gulf between the world of the food movement and that of the mid-sized farms I grew up on and around. I watch countless cool-but-teeny urban ag projects pop up in cities across the U.S. that inspire but grapple with problems of scope. Meanwhile, Big Ag strengthens its hold and swallows up everything in the wide miles between — where much of our food actually comes from, where I come from. And so, whenever classic country comes on, I get dust in my eye thinking of the red dirt roads and the disappearing, simpler life they lead to. But was it ever really so simple?

My music-induced nostalgia has international company. In a Radiolab segment on music, Columbia University anthropologist of music Aaron Fox explains that, counterintuitively, country and western has roots in American urbanization. The first hit country song popped up in 1927, the year the U.S. population majority transitioned from rural to urban. “Country music is born when the country becomes a nostalgic ideal,” Fox says in the Radiolab segment. The crying steel guitars and vocalizations conjure up feelings of migration and regret, he says. And now, classic country is popular in developing countries, where everyone from Australian Aborigines to Zimbabweans (who fill soccer stadiums to see Don Williams play) understands the language of leaving the land behind afresh.

Drawing inspiration from Ben Adler’s mixtape love letter to the parks that birthed hip hop, I planned on writing about the waning of the family farm and accompanying it with a mix of my favorite old, nostalgic country songs. Combining Patsy Cline and sad stats about disappearing U.S. farmland proved too depressing for me, though, and the story stayed stuck until author, farmer, and chef Dan Barber visited the Grist office. Beyond being a third-plate philosopher and first-rate raconteur on food issues, he caught my ear and surprised me when he skipped the farmers market to argue for the plight of mid-size farms like the one I grew up on.

Constituting about 45 percent of our agriculture, these farms are “too big to pack up a pickup truck and sell at a farmers market, but they are increasingly much too small to compete in the Walmartification of the food system,” says Barber. “They’re literally stuck in the middle.”

Fifth-generation farmer and Daily Yonder columnist Richard Oswald echoes this sentiment. “In America, we have two really visible types of agriculture,” he said on a recent The Farm Report podcast. “The large corporate agriculture … and then we have the local food movement.” In the middle, he says, are the family farmers who possess the cumulative knowledge of the land locavores romanticize, but have also modernized operations in ways the food movement might not approve of. As a result, food writers “tend to lump us all in with the industrial food folks. It makes it really difficult for people like me who have to struggle and fight just to stay on the farm at all.”

A recent USDA report lays out what that means on the ground: “The median farm operator household consistently incurs a net loss from farming activities, which means that most farm operator households rely on off-farm income to sustain them.” Or, to put it in popular decorative-plate terms: “Behind every good farmer, there’s a wife who works in town.” Whether it’s the husband or wife making that daily trip to an office job, the situation is often perilous, and the family farmers who are still in the game usually aren’t in it to make the big bucks.

There are reasons beyond nostalgia why foodies should care about the mid-sized farm: Without them, it’s easy to imagine a future where Big Ag dominates the American diet and local food remains a niche for those who can afford it. “[The small specialty farmer] isn’t feeding a lot of people. Essentially they’re bringing to market these cream-of-the-crop type of vegetables that are very hard on the soil,” Barber says.

And we’re already headed in that direction: “We just plowed up a million acres of virgin prairie in the last 10 years at the heart of the farm-to-table movement,” Barber says.

So what to do? Barber hopes we can broaden the food movement for the sake of the food system at large. “It’s important to support the farm-to-table movement,” Barber says, “but we somehow have got to make the issue of mid-size farming sexy and approachable.”

While I agree that much can and must be done to make mid-size farming sexy to foodies, turning a conventional farm into a sustainable one is no easy task. Struggling to make ends meet does not foster an environment of innovation, experimentation, and complicated crop/animal rotations. Beyond issues with infrastructure and outreach, we also have to find common ground in two cultures that more often seem to clash.

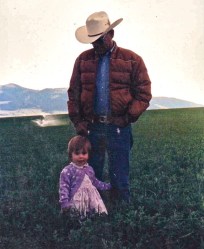

The author with her grandfather.

This tension is part of my family lore. When my grandfather dropped my mother off at college, it wasn’t at the university he preferred. He would have liked her to study at the farm school where all the good neighbor kids went. It had an excellent ag program, and it was closer to home. Instead, his oldest daughter picked the University of Montana in Missoula, the Montana equivalent of Portland. When she got out of the truck, my grandpa took a good, hard look around at her classmates and muttered, “Goddamn beatniks.”

That kind of sentiment gets passed down just like the land. Thirty years later, “Californian” was still one of the worst insults you could throw out at my grade school. We snickered at tourists sitting white-knuckled in Lexuses behind highway cattle drives. I grew up with kids who weren’t allowed to watch Captain Planet. There’s a common sentiment that goes beyond your standard outsider shunning: These city folk think they know better than us with their fancy cars, magic rings, and cool berets.

And for all of the cultural invasion of farmers markets, perception of “flyover country” hasn’t changed much either. A coworker was surprised that I love Montana and said that my haircut suggested I hated the place. One well-meaning friend from the city took a look at the wide-open spaces surrounding our ranch and said, “It’s a miracle you turned out so … cultured.”

In order to save mid-sized farms for the sake of the food movement and the people who own them, we’ll need to learn how talk to each other first. To urban foodies: Rural life is more nuanced and intelligent than you might perceive. To the farmers: There’s a generation of folks who are interested and educated about food — and they’re willing to pay more for a greener effort and more stable farming system.

My dad once told me a bit of my grandfather’s life wisdom at an apt moment. “You can shovel shit for a living so long as you do it better than the next man,” he said as I chipped at a pile of frozen manure. While I think he means I should be scrambling up the ladder of the lucrative field of environmental journalism, I’m going to take a completely unrelated lesson from it.

I’m off the farm, but in a way I’m still shoveling shit. I push around digested material; ideas often go through four stomachs before they end up under my byline. But I’ve learned that by breaking down the cellulose and straining out the nutrients, sometimes you lose complexities and nuance. You end up with beatniks and a big pile of nostalgia. I know better now than to reduce my homeland to songs about lost lovers and shuttered farms. There’s still opportunity in that land and people are there trying to seize it. And I want to do farm life more justice than the next man.

So, rather than sad stats and old songs, I’m going to talk to someone on the ground about the gap between the food movement and mid-size operations, and what it would take to turn a somewhat-conventional farm into a sustainable one. I’m going to talk to my dad.

Next: How to break the cycle of bigger farms and fewer farmers.