When I reached Mike Williams by phone last week, the head of poultry science at North Carolina State University was in the field, visiting barns. At each stop, he came across the same sad scene: thousands of dead, sodden birds.

Some 2 million chickens and at least 4,800 pigs drowned after Hurricane Matthew hit the state earlier this month. “The growers are obviously emotional,” Williams told me. The storm inundated massive pools of hog feces and piles of chicken manure, spreading pollution from North Carolina’s thriving pork and poultry industry into the surrounding woods, rivers, and swamps.

“I’m seeing a lot of devastation out there,” said Rick Dove, senior advisor to the environmental group Waterkeeper Alliance, after flying over North Carolina’s coastal plain last week to survey the hurricane’s destruction, which killed at least 26 people in the state and caused $1.5 billion in damages.

For a state that’s regularly flooded by hurricanes, it might seem strange that it’s also flooded by hogs. The industry surged in the early ’90s, in response to government incentives and lax regulation, and by 1996 North Carolina had become the second-biggest pig state in the nation, after Iowa.

And these weren’t your old-fashioned swine farms — hundreds of pigs were confined in close quarters inside long, low aluminum houses. Farmers washed thousands of gallons of pig feces into earthen pits, called “lagoons” in the industry. They were clustered in the inexpensive and swampy lowlands, where the neighbors were disproportionately poor minorities.

Then came the hurricanes: In 1996, Fran killed 24 people and caused $2.3 billion in damages, followed in 1999 by Floyd, which killed 52 and cost $6 billion. When the floodwaters from both storms hit the new hog facilities, all hell broke loose.

Fran killed some 16,000 pigs and washed their feces into rivers. Floyd drowned 30,000 pigs — photographs from the air show dozens of lifeless pink bodies bobbing around submerged barns — and on many farms, the heavy rains breached the earthen walls holding back the lagoons of liquid hog feces. Rivers of sludge spilled out.

So is Hurricane Matthew déjà vu all over again? Let’s take a step back and look at what put hog farms in the path of hurricanes.

Why is eastern North Carolina full of hog farms?

Rick Dove, Waterkeeper Alliance

It was human ingenuity, not environmental appropriateness, that gave rise to the hog industry in North Carolina. The industry really took off in the ’80s when farmer Wendell Murphy, followed by the company Smithfield Foods, hit on a series of breakthroughs that made hog farming much more economically efficient and profitable — including storing manure in cheap, but flood-vulnerable, lagoons.

Farmers in the state needed a low-cost waste solution because manure — prized as a fertilizer in other regions — was essentially worthless in North Carolina (see the next section). So farmers dug giant pit toilets in the ground, and when those filled, they pumped the manure slurry through irrigation pipes to spray onto their fields.

After Murphy found his stride as a farmer, he went into politics and gave his industry a boost. He helped pass laws exempting swine barn materials from sales tax and making hog houses immune to zoning regulations. Over the next decade, from 1987 to 1997, the number of hogs in the state increased sevenfold as revenues more than tripled. The legislature has since amended the law to give counties zoning authority over large poultry and livestock farms.

Why is this a problem?

It actually doesn’t make much sense to raise hogs in North Carolina, because there’s not much cropland, which means the state has to import animal feed. Long trains hauling corn zip from the Midwest to the mid-Atlantic day and night.

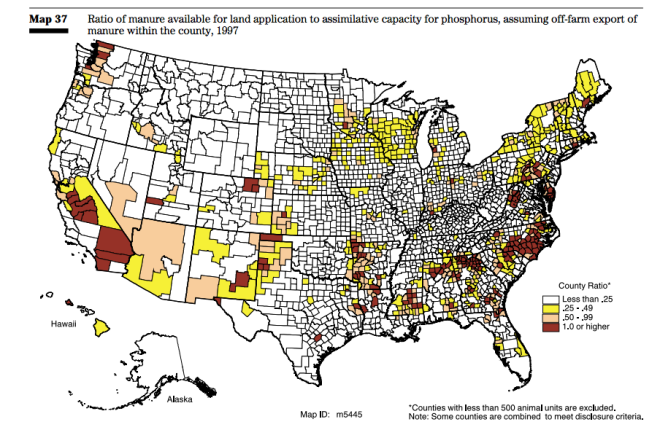

When animals live near the crops that feed them, their manure can serve as fertilizer in a neatly circular system. In Iowa, there’s so much corn that farmers frequently pay their neighbors for the honor of taking their pig poop, said Daniel Anderson, a manure expert and assistant professor at Iowa State. But not in North Carolina; eastern North Carolina already had more than enough manure to fertilize its fields by 1997, as you can see on this map — and that was before the construction of many new turkey and chicken houses.

NRCS

Farmers in brown counties would have to truck their manure to some other non-brown county — which is ridiculously expensive when you are dealing with watered-down lagoon poo. As the Natural Resource Conservation Service put it, even for the less-vulnerable tan counties on that map, “Counties in this category probably have significant animal waste problems.”

This isn’t to say that Iowa doesn’t have water pollution problems — it has plenty — but these problems in the Midwest come mostly from fertilizer washing off fields. About a third of this fertilizer is manure, but if farmers weren’t using manure, they’d have to use synthetic fertilizers instead, which would cause sickness and environmental destruction downstream, too.

We just haven’t figured out how to completely prevent fertilizer from washing off fields — it’s a problem for both organic and conventional farming. In contrast, it’s an (avoidable) error of planning to pack so many animals into one area that their density virtually guarantees water pollution.

Have we learned nothing from previous floods?

Hog farming is still concentrated in eastern North Carolina, but it has moved to higher ground. In 1997, the state government put a moratorium on new hog facilities and offered farmers several options for getting out of flood zones, upgrading waste management, and taking defensive measures.

After Hurricane Floyd, North Carolina set up a program to buy swine farms in floodplains. The state spent $18.7 million to buy 42 farms, said Brian Long of the North Carolina Department of Agriculture. Thanks to that program, there’s much less damage this time around, according to Stephanie Hawco, deputy secretary for public affairs at the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality.

Rick Dove, Waterkeeper Alliance

We’ll have to wait until the floodwaters recede to be sure, but officials say that the hurricane doesn’t appear to have breached the berms of any lagoons. However, a couple of the pictures from Dove, of Waterkeeper, show something that looks suspiciously like a breach. There’s no disagreement that the waters did inundate lagoons on 11 hog farms, according to a statement from the North Carolina Pork Council.

That’s not as bad as a breach, which spills sludge out onto surrounding land, said Bill Showers, professor of marine, earth, and atmospheric sciences at North Carolina State. “When a lagoon is inundated, there will be a certain amount of mixing, but not as much. They say that dilution is the solution to pollution, and there’s just a tremendous amount of water out there right now.”

Dove told me that the damage was likely just as bad as Floyd, but the number of breached or flooded lagoons he counted — 14 or 15 — is roughly consistent with Pork Council tally. After Floyd, 50 lagoons flooded and six breached, according to the Pork Council.

There was no moratorium on building new poultry farms, and those have been popping up on inexpensive low-lying land, Dove said. No one I talked to could tell me if the state has any incentives or rules to keep poultry farms off floodplains. Williams from North Carolina State and Long from the Department of Agriculture said they weren’t aware of any such guidelines.

Rick Dove, Waterkeeper Alliance

So, what’s next?

The sense I got from talking to North Carolina regulators and experts was that farmers had prepared as well as one could be expected for a 500-year flood. According to that way of looking at things, the problem isn’t that these farms are in a vulnerable area — it’s that they are being hit by hurricanes with improbable frequency. “As one farmer just put it, I’ve now had three 500-year floods in my lifetime,” Williams said. “I personally do believe we are being impacted by climate change.”

For environmentalists like Dove, however, this flood shows that the system is still broken. “It just doesn’t make sense to have all these facilities here in harm’s way,” Dove said. “They don’t have to leave, but they can’t make us pay for their cheap manure management systems.”

There are other options besides inexpensive lagoon systems. In Iowa, most hog houses sit over the manure pits, which makes them much less vulnerable to flooding.

There are new systems for separating water from solids. There are methane digesters that capture greenhouse gases from manure and turn it into fuel. But making these changes is expensive — like $6 million for a fancy new methane digester.

Rick Dove, Waterkeeper Alliance

A cheaper solution would be to at least ensure that new concentrated animal feeding operations have enough cropland in the surrounding area to absorb all their manure. Many local governments already have rules to keep CAFOs from overwhelming their “manure-shed,” but these rules don’t apply to farms already in place.

If North Carolina wants to end the pattern of water pollution, it has to find a way to spread out the livestock or treat their waste. And the state needs to face the fact that once-in-a-lifetime floods are now hitting more than once a decade.