Earlier this week, Canada’s auditor general reported that Indigenous Services Canada (ISC), the federal department responsible for coordinating emergency management services to First Nations, failed to provide Indigenous communities with adequate resources to deal with climate disasters. According to the report, it’s likely that ISC is incurring “significant costs” to respond to climate emergencies that could have been mitigated or avoided.

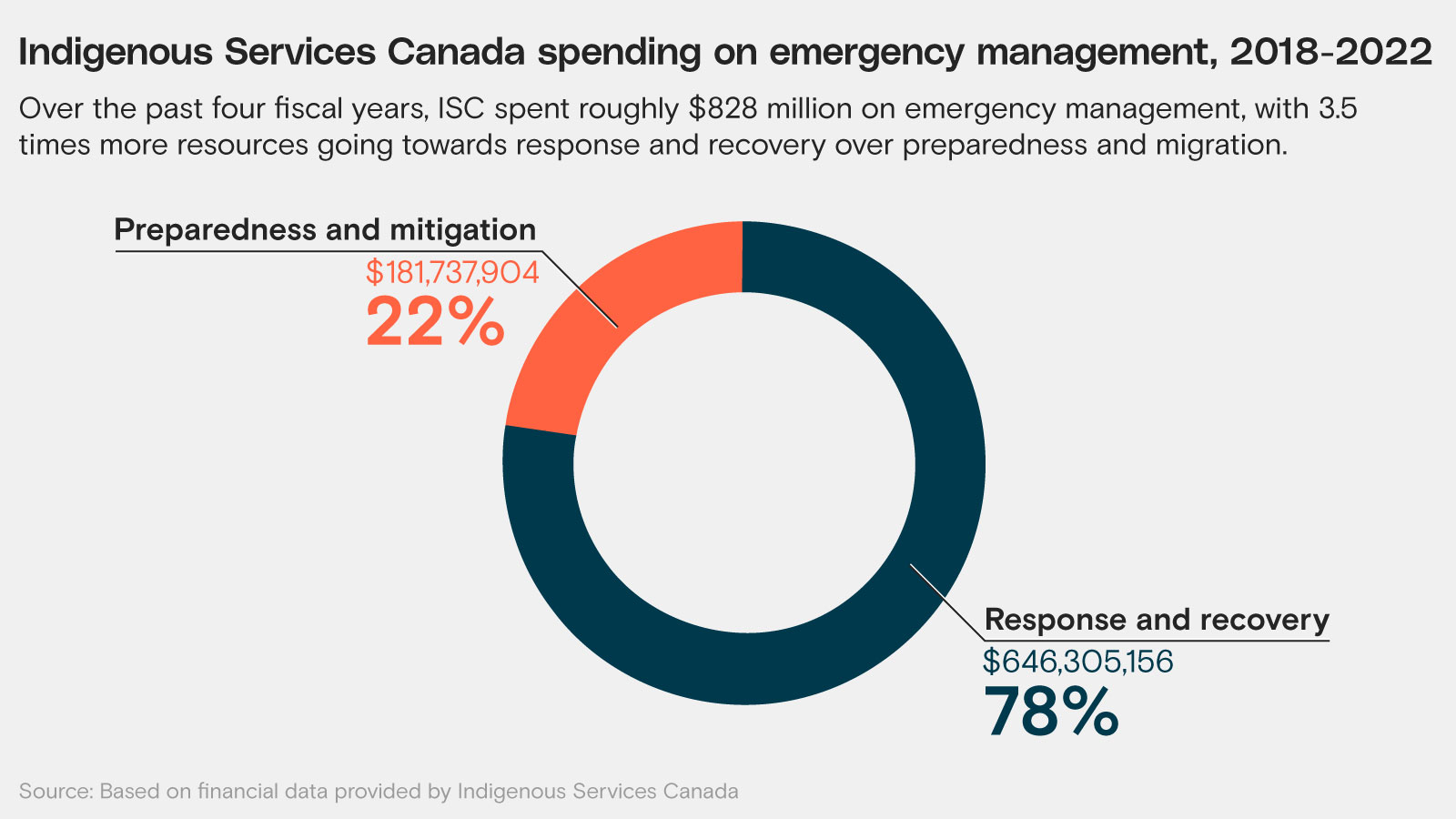

The report details how various shortcomings in the department have led to underfunding and understaffing, ambiguity around jurisdictional responsibility, and a lack of disaster preparedness that puts First Nations communities at greater risk of harm from climate disasters. Notably, the audit found the department spent nearly 4 times more on emergency recovery than emergency preparedness: for every $1 invested in mitigation, $6 could be saved in emergency response and recovery costs.

First Nations communities are 18 times more likely to be evacuated in the wake of climate disasters than non-Indigenous communities, according to a 2017 ISC study. That’s due to aging infrastructure, weak socioeconomic supports, homes in remote locations, and a history of communities being relocated from traditional lands to flood and wildfire-prone areas.

Despite a similarly poor review of ISC operations in 2013, Karen Hogan, Canada’s auditor general, said she was frustrated that the department had made no improvements in a decade. “Indigenous Services Canada still has not identified which First Nations communities most need support to manage emergencies,” Hogan said in a press conference on Tuesday. “If the department identified these communities, it could target its investments accordingly.”

ISC has maintained a backlog of 112 eligible, unfunded projects, including building culverts and dikes to prevent seasonal floods, that could help First Nations deal with climate disasters and reduce financial costs borne by the state. As of April 2022, 74 of those projects had been in the department’s backlog for more than 5 years. According to the report, with the department’s current budget it would take nearly 25 years to fund and complete those projects – barring any new proposals.

“ISC said they couldn’t get to these projects because of funding shortfalls,” said Doreen Deveen, director of Canada’s auditor general’s office. “Until they invest more in prevention and mitigation, First Nations will continue to be in a more vulnerable position.”

ISC is also responsible for ensuring that First Nations receive culturally appropriate resources and that service quality is comparable to similarly-sized non-Indigenous communities. However, without defining expectations for the quality of services to First Nations, or consistently monitoring service delivery, the department has fallen short of its expected mandates. The report also found that ISC lacked an updated emergency management plan as required under the Emergency Management Act.

Those issues, the report says, “increases the risk that some First Nations communities will not receive emergency services when they need them the most… and can lead to delays in First Nations receiving supports during an emergency. Timely response is critical during emergencies because human lives and infrastructure are at risk.”

More than 1,300 emergencies have impacted First Nations communities in the last 13 years, leading to nearly 600 evacuations affecting almost 130,000 people. The longest evacuation affected members of the Peguis First Nation in Manitoba, after heavy flooding in 2011. As of May of last year, 91 residents were still unable to return home because of insufficient housing.

Patty Hajdu, Minister of Indigenous Services, acknowledged that First Nations are on the front lines of climate change and said that it will be crucial to foreground their input in emergency management planning. “Above all, this work must be led in true partnership with First Nations and all orders of government, ensuring that equal participation and equitable resources are available,” Hajdu said.

Though the auditor general’s report offers various recommendations on how to address these problems, none explicitly outline increased financial investment in First Nation communities.

“Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) is developing a comprehensive action plan to further address these recommendations so that First Nations have the tools and resources they need to prepare, prevent, mitigate, and respond to disasters caused by natural hazards, including those resulting from climate change,” said ISC spokesperson Nicolas Moquin, in an email. “ISC acknowledges that First Nations require emergency management plans that are up to date and address the specific risks faced by their communities.”

Representatives of the Assembly of First Nations could not be reached for comment.

For Kailea Frederick, a climate justice organizer at NDN Collective, direct access funding is a critical component of supporting Indigenous Peoples who have been long impacted by climate change.

“There’s a misleading idea in global north communities that there are public programs and funding mechanisms for people,” Frederick said. “But the reality is that those agencies have been and continue to show up short for Indigenous communities.”

The audit comes as world leaders meet at the U.N. climate summit, COP27, which released a draft final assessment early Thursday that made light mention of “loss and damage” funding. That funding asks industrialized countries to provide financial support to developing nations dealing with the effects of climate change. However, funding gaps – reflected in ISC’s emergency service response to First Nations in Canada – could be further entrenched as tangible plans on climate funding have yet to be proposed.

Frederick says that Indigenous peoples must be included in conversations around climate finance programs to ensure that they are designed and implemented effectively.

“There needs to be [recognition] within the federal governments in the US and Canada that Indigenous peoples and First Nations still exist and that they’re not receiving adequate support before, during or after weather related events,” Frederick said. “That has devastating consequences.”