This story was originally published by ProPublica. It was produced in partnership with Georgia Health News, which is a member of the ProPublica Local Reporting Network.

Mark Berry raised his right hand, pledging to tell the whole truth and nothing but the truth. The bespectacled mechanical engineer took his seat inside the cherry-wood witness stand. He pulled his microphone close to his yellow bow tie and glanced left toward five of Georgia’s most influential elected officials. As one of Georgia Power’s top environmental lobbyists, Berry had a clear mission on that rainy day in April 2019: Convince those five energy regulators that the company’s customers should foot the bill for one of the most expensive toxic waste cleanup efforts in state history.

When Berry became Georgia Power’s vice president of environmental affairs in 2015, he inherited responsibility for a dark corporate legacy dating back to before he was born. For many decades, power companies had burnt billions of tons of coal, dumping the leftover ash — loaded with toxic contaminants — into human-made “ponds” larger than many lakes. But after a pair of coal-ash pond disasters in Tennessee and North Carolina exposed the environmental and health risks of those largely unregulated dumps, the Obama administration required power companies to stop using the aging disposal sites.

Berry had spent nearly two decades climbing the ranks of Southern Company, America’s second-largest energy provider and the owner of Georgia Power. By the time he was under oath that day, company execs had vowed to store newly burnt coal ash in landfills designed for safely disposing of such waste. But an unprecedented challenge remained: Figuring out what to do with 90 million tons of coal ash — enough to fill more than 50 Major League Baseball stadiums to the brim — that had accumulated over the better part of a century in ash ponds that were now leaking.

Georgia Power would have to shut down roughly 30 ponds from the Appalachian foothills to the wetlands near the Georgia coast. After draining all the ponds, the company would have two options for disposing of the highly contaminated dry ash left behind: It could either move the ash into a landfill fitted with a protective liner, or pack the dry ash into a smaller footprint and place a cover on top — leaving a gaping hole in the ground that, in some places, would be larger than Disneyland. The former would cost more but vastly reduce the possibility of toxic leakage; the latter lowered expenses but would perpetually risk contaminating drinking water in neighboring communities.

As scientists had grown more aware of the threat posed by coal ash, Southern states like Virginia and North Carolina had forced utilities to move ash into lined landfills. But Georgia was something of an outlier. The state historically was known as a coal ash capital, a place where lawmakers touted their pro-business bona fides by denouncing regulations, and Georgia Power had a track record of delaying or blocking efforts to regulate pollution. The company was lobbying hard for the cheaper option.

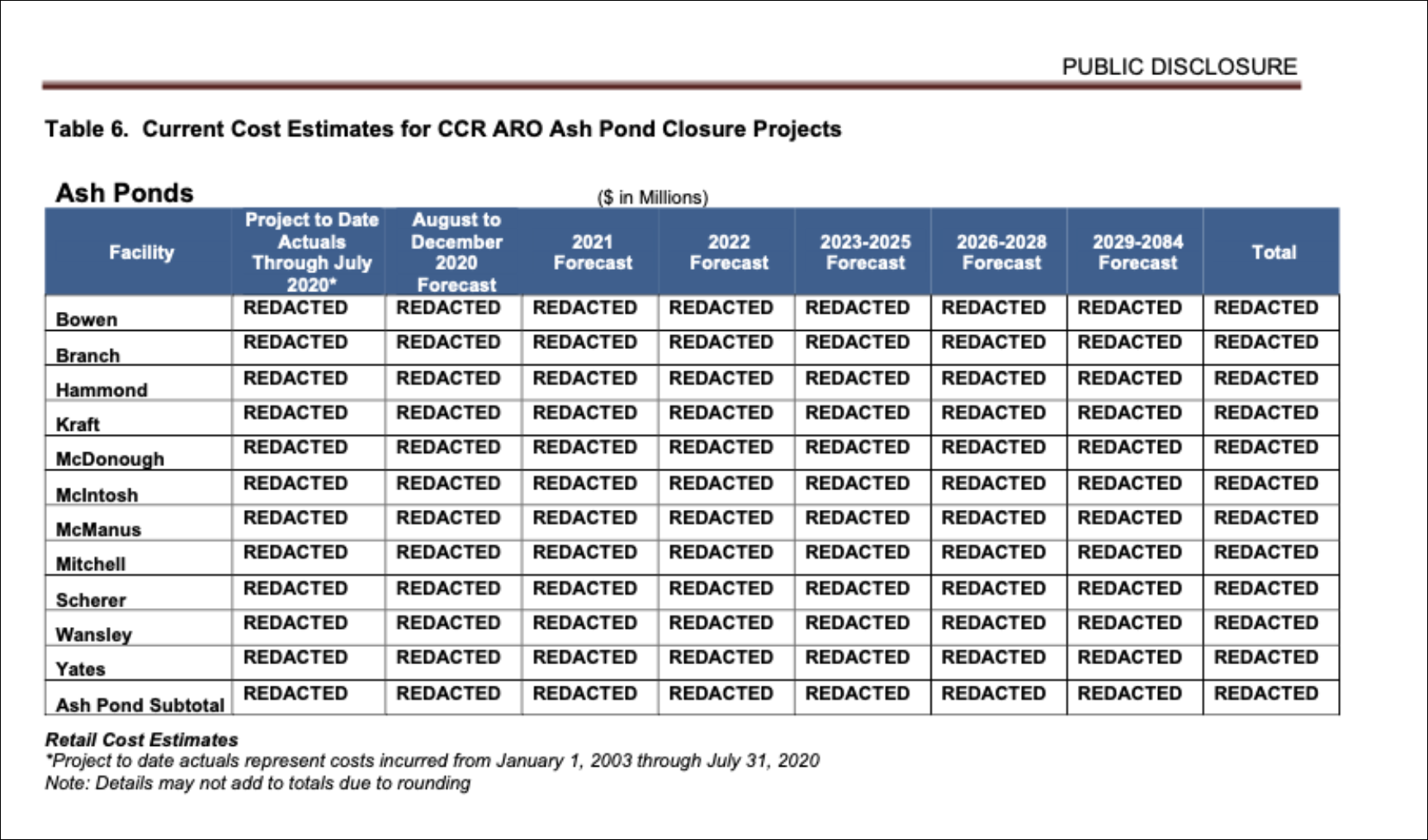

Of course, the $7.3 billion price tag wasn’t all that cheap. Sitting on the Georgia Public Service Commission’s witness stand, Berry and his top deputy spent hours arguing that the whopping costs of cleaning up Georgia Power’s coal-ash ponds should be passed along to its customers. If Berry could persuade the regulators that the costs were both “reasonable” and “prudent,” the company could tack a monthly fee onto the bills of 2.2 million residential customers for decades to come, which would work out to each customer footing $3,300 of the bill to clean up the company’s mess. If he failed, the commissioners could effectively force Georgia Power to eat those costs — a major blow to investors in a publicly traded company that has annual operating revenues of over $8 billion.

During Berry’s testimony, PSC commissioner Tim Echols said he has concerns about putting ratepayers on the hook for the costs of cleaning up the ash ponds — and whether Georgia Power is spending more than it has to. “This is enormously expensive,” he said.

Berry didn’t mention that the cleanup costs could increase by billions of dollars if Georgia’s environmental officials adopted the safer standards used by neighboring states. Anticipating Echols’ next question, Berry said that Georgia Power’s $7.3 billion plan was the “most cost-effective way” to comply with coal-ash regulations.

“If we were to do something less,” Berry added, state environmental officials “would force us to go back and redo what we did not do right the first time.”

Had those five energy regulators swiveling in their chairs asked more pointed questions about Georgia Power’s waste-disposal practices, Berry would have been pressured to tell a long-hidden story about ash and avarice. In the second half of the 20th century, Georgia Power had saved money by building some of America’s largest coal-ash ponds without a protective liner underneath, despite knowing some of the risks of contaminating residents’ drinking water. It had also sought to do as little as possible to protect drinking water that’s now believed to be tainted by coal-ash toxins.

A yearlong investigation by Georgia Health News and ProPublica has revealed that Georgia Power and its parent company have spent millions of dollars on lobbying tactics to dodge billions in environmental costs. Thousands of pages of previously unpublished documents obtained by the news organizations shed new light on how Georgia Power leveraged political tensions to reduce a massive financial liability that could decimate its bottom line — and how it pushed disinformation to distance itself from patterns of sickness among people who lived near its coal-ash ponds.

Georgia Power spokesperson John Kraft declined to answer most of the news organizations’ questions and to make Berry available for an interview. Kraft said in a statement that Georgia Power has worked to “quickly and safely begin closing all of our ash ponds” in a manner that complies with federal and state coal-ash regulations.

But at the hearing in April 2019, none of the energy regulators pressed Berry on the topic of coal-ash contamination. Because they didn’t ask, Berry remained mum. His silence would make it easier for the regulators to stomach the idea of passing the cost of the cleanup on to customers — and easier for Georgia Power to avoid responsibility for the much more expensive fix. And it allowed Georgia Power to continue its longstanding efforts to cover up the hazards of coal ash across the state, most notably in a tiny town where the company operates the largest coal-fired plant in the Western Hemisphere.

In the spring of 1974, as Atlanta Braves slugger Hank Aaron shattered Babe Ruth’s home run record and gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson first forged a friendship with Governor Jimmy Carter ahead of his presidential campaign, a towering attorney named Tommy Malone set his sights on a white two-story house in the sleepy central Georgia town of Juliette.

Malone would, years later, become one of the state’s most successful medical malpractice attorneys. At the time, though, he ran a firm that had hit a financial rough patch. To cover payroll, he’d landed a gig representing Georgia Power, which sought to buy thousands of acres for a new coal-fired power plant. Georgia law allowed the utility to condemn nearly any property it wanted. But the actual use of eminent domain spurred negative headlines and local resentment — both of which could undermine Georgia Power’s carefully cultivated corporate reputation. So Georgia Power dispatched Malone to convince residents of Juliette to sell their land. He’d been scouting properties along Luther Smith Road, a winding two-lane street hugged by Georgia pines. The white house belonged to a retired cowboy named Brack Goolsby. Malone hoped Goolsby might willingly sell more than 300 acres.

The Goolsby family home had stood long before Brack rode his first horse, before his hometown was established in the 1880s, and even before General William Tecumseh Sherman’s troops passed through it on the infamous March to the Sea. Brack’s family had such deep roots in Juliette that the road he lived on was named for his Uncle Luther.

When Luther Smith died in the early 1950s, he left the family home to his nephew. Brack and his wife, Betty, raised two sons, Mark and Bob, who grew up exploring the family’s untamed forests. Two decades later, when Georgia Power announced its plans to build a 12,000-acre plant site abutting Luther Smith Road, some neighbors balked. They fought the company’s use of eminent domain. One farmer’s wife mailed a desperate letter to Carter, writing that their land, tended by them through good times and bad, is “not for sale at any price. … We hold precious its beauty, the quiet and peace.”

A small-town peanut farmer who frequently rafted down Georgia rivers, Carter raised concerns to his aides about the plant’s environmental impact. The aides peppered Georgia Power Executive Vice President Harold McKenzie with questions about how much energy — and pollution — the plant would generate. When the conversation turned to a waste-disposal site nearly the size of Central Park, one Carter aide asked McKenzie: What do you do when the ash pond fills up?

Clean it up, McKenzie promised, according to the Carter administration’s notes from that meeting.

Carter’s hands were ultimately tied: Georgia lawmakers had previously granted the utility immense power for an investor-owned company. (A spokesperson for President Carter did not respond to an interview request.) Not only could Georgia Power use eminent domain to condemn property without public hearings, it had the authority to build new plants nearly wherever it wanted. Georgia Power quickly acquired the land for its new coal-fired plant site. The company would eventually name the plant after McKenzie’s boss, CEO Bob Scherer, who guided Georgia Power through a tumultuous period marked by the oil embargo of the 1970s.

In the midst of Georgia Power’s land-buying spree, Brack Goolsby took Malone’s offer and sold 312 acres of land for $207,524. Goolsby kept roughly 30 acres and his house, which was on the other side of Luther Smith Road from the Plant Scherer site. Goolsby was relieved that the home would remain there for his kids and grandkids. For several years, whenever he turned right out of his driveway, Brack watched as the company felled trees and dug deep into the red Georgia clay to build a pit for all the ash left over from burning mountains of coal.

In late 1976, two years after Georgia Power bought the Goolsbys’ land, Congress passed the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, granting the newly formed Environmental Protection Agency the authority to regulate the disposal of waste, including everything from household garbage to some radioactive materials. The EPA considered whether coal ash should be classified as a hazardous waste. The designation would have required electric utilities to install a protective liner under every existing or proposed ash pond to prevent contaminants from seeping into underground aquifers.

Roughly four out of five Americans get their household water from their city or county. That water is typically sourced from lakes and rivers, tested for toxins, treated, and piped directly to homes. But 43 million people, largely in rural areas, rely on a private drinking well that pumps up groundwater from an underground aquifer.

By the time the act was passed, scientists knew coal ash contained trace metals such as arsenic, chromium, lead and other chemicals recognizable from the periodic table, all of which could slowly infiltrate groundwater. In 1979, Tennessee ecologist Robert Van Hook wrote in the peer-reviewed journal Environmental Health Perspectives that the trace metals in coal ash “may constitute human health problems,” including increased risk of cancer. With utilities burning record levels of coal each year, and thus producing more ash, Van Hook called for an evaluation of the “potential for contamination of drinking water supplies by trace elements in leachates from settling ponds.”

Most ash ponds at that time had not been built with protective liners, and America’s power company execs feared that retrofitting them would collectively cost more than $20 billion — $72 billion in today’s dollars. Coal ash’s designation as “hazardous” would not only impact Georgia Power, but also Alabama Power, Gulf Power, and other utilities in the Southern Company system. Southern Company soon found an ally in Congressman Tom Bevill, then a seven-term Alabama Democrat whose father had mined coal on the northwest outskirts of Birmingham, where coal had burned at one of the system’s oldest plants since World War I.

During a speech in 1980, as lawmakers debated a bill to strengthen the EPA’s ability to enforce waste regulations, Bevill told his colleagues he knew of no evidence that coal ash “has ever presented a substantial hazard to human health or the environment.” He proposed to exempt coal ash from hazardous waste regulations until the EPA conducted more studies. His amendment passed with minimal attention.

The Bevill Amendment ushered in an era during which Georgia Power and other utilities could keep dumping coal ash into unlined ponds — despite emerging evidence of contamination. That same year, an EPA study described how trace metals in coal-ash ponds could seep deep enough into the ground to come into contact with groundwater. Recognizing the threat, some utilities changed their coal-ash practices absent any federal mandates, including the Northern Indiana Public Service Company, which installed a $2.3 million liner under an ash pond that was leaking wastewater. And while some states like Maryland and Louisiana created tougher regulations for coal-ash disposal, other states, such as Georgia and Ohio, did not.

By the early 1980s, Southern Company execs knew that storing coal ash in ponds without a protective liner could contaminate groundwater. Internal corporate filings obtained by Georgia Health News and ProPublica from multiple state archives show that an in-house research and development company called Southern Company Services Inc. was established to design plant sites for utilities in the Southern Company system. In the 1970s, Florida environmental regulators denied an SCSI-designed ash pond proposal for Plant Crist in Pensacola, which was owned by Southern Company’s Gulf Power, because the plans lacked a “suitable liner … constructed to prevent leaching,” according to the records. In response, from 1977 to 1982, SCSI developed a $20 million waste-disposal system to hold dry coal ash with a liner underneath.

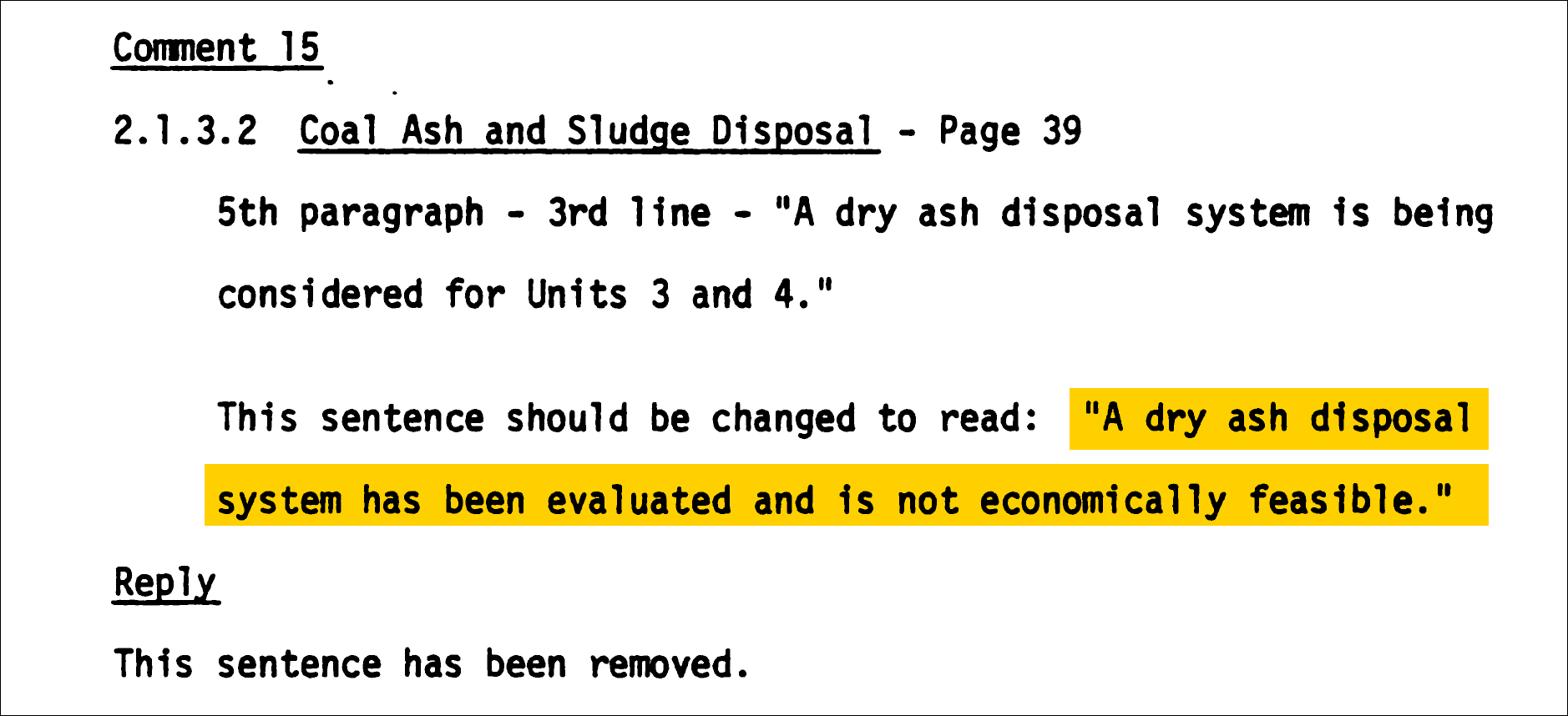

Simultaneously, SCSI designed Plant Scherer in Juliette, where it could have included a liner like it did at Plant Crist. However, Georgia Power claimed in filings that a protective liner at Plant Scherer was “not economically feasible.” Indeed, the installation of a liner at Plant Scherer’s ash pond could have cost as much as $95 million, according to industry estimates from the time.

When Georgia Power fired up Plant Scherer’s first unit in late 1982, water and ash flowed into a giant hole buttressed by an earthen berm that stood 100 feet tall. Engineers had designed the pond to be large enough to accept waste into the next century. With each week that passed, tiny contaminants in the ash pond seeped through soil under the pond and into an underground aquifer, according to company filings. And as weeks turned to years, water in the aquifer slowly carried those contaminants closer to Luther Smith Road.

Water is part of Andrea Goolsby’s earliest memories of her grandparents’ home. She watered her father’s tomatoes, sipped from her grandfather’s garden hose, and ate fresh strawberries washed by her grandmother. The idea that Brack and Betty Goolsby’s water might be contaminated by the nearby power plant never figured into family conversations back then. It hadn’t crossed the minds of Andrea’s grandparents, parents, or sisters, nor those of her aunts, uncles, or cousins, who also lived near Plant Scherer.

“I’d see the ash pond,” Andrea later recalled. “It just looked like a big lake.”

Bevill had indicated back in 1980 that two years of EPA research would definitively rule out the possibility that coal ash could be harmful to human health. But the agency didn’t issue a report for another eight years, informing Congress in 1988 that while coal ash had caused some cases of groundwater contamination, the agency had insufficient evidence to reclassify coal ash as a hazardous waste. That same year, investigators with the Georgia Environmental Protection Division collected groundwater samples from several older Georgia Power plant sites that revealed evidence of contamination. Groundwater at Plant McManus in Brunswick contained chromium at levels 16 times higher than Georgia deemed safe for drinking. And at Plant Mitchell in Albany, groundwater contained levels of lead that exceeded federal drinking water standards. The investigators, who estimated that thousands of residents near the plants relied on private wells for drinking water, recommended further examination of groundwater contamination. (Current EPD spokesperson Kevin Chambers said the division has no records indicating that officials followed up with subsequent investigations; Georgia Power declined to elaborate on the findings of the reports.)

Georgians who lived near coal-ash ponds, including ones at newer plant sites like Scherer, told GHN and ProPublica they were never informed by the EPD or Georgia Power that their drinking water might be contaminated. As a child, Andrea had played at Plant Scherer cookouts held for hundreds of employees, including her father and uncle. As a teenager, she benefited from Georgia Power’s tax dollars that helped fund one of the state’s best public school systems. Many of Andrea’s neighbors believed that Georgia Power had revived Juliette, a place that, after serving as the backdrop for the 1991 Kathy Bates film “Fried Green Tomatoes,” became a quaint symbol of small-town America.

Andrea loved her small town. Juliette felt safe, a place untouched by tragedy. She had experienced little in the way of loss until one windy Thursday in November 2002. Andrea, then a 15-year-old high school student, watched her grandfather writhe in pain on the living room couch. Earlier that week, Brack had been diagnosed with late-stage cancer in his bile duct, a tube that connects the liver to the small intestine. She hugged him tight, worried it might be the last time. Indeed, it was. Brack died the next day.

Three days later, Andrea stayed home from school to say goodbye to her grandfather, who was buried at the Juliette United Methodist Church cemetery, two miles north of Plant Scherer’s front gates. His death would be first in a string of nine cancers among her extended family members who lived near the plant. At first, no one suspected that the sicknesses that came next — a great aunt diagnosed with breast cancer, two distant relatives who died from leukemia — were anything but coincidental.

But then Andrea’s family noticed changes around the family’s land: Their plants and animals were dying more often than usual. The Goolsby family began to wonder why, after years of good health, a wave of sickness and death had descended on Luther Smith Road.

In December 2008, four months after Andrea’s second relative died of leukemia, more than a billion gallons of coal ash slurry broke through a dike at the Tennessee Valley Authority’s Kingston Fossil Plant. A wave of dark, gray sludge spread over 300 acres, as deep as 6 feet, downing power lines, pushing a home off its foundation, and filling a nearby river with toxins. As the hidden dangers of coal ash flooded into plain sight and workers began cleaning up the waste, environmentalists swiftly called for stricter regulations, including a liner mandate to prevent toxins from seeping out of unlined ash ponds.

Until the Kingston spill devastated the 6,300-person town of Harriman, located 250 miles north of Juliette, air pollution from coal-fired power plants had long overshadowed the peril of groundwater contamination caused by coal ash. Around the turn of the millennium, U.S. Attorney General Janet Reno had filed an epic lawsuit against Southern Company and other utility giants for allegedly violating the Clean Air Act. Plant Scherer was one of more than two dozen coal-fired plants that, according to the EPA, had “illegally released massive amounts of air pollutants.” (Southern Company wrote in an annual report that “the action against Georgia Power has been administratively closed.”) As Reno’s lawsuit grabbed headlines, Southern Company quietly partnered with its allies to quash a stricter coal-ash regulation.

In the late 1990s, nearly two decades after the Bevill amendment exempted coal ash from being classified as a hazardous waste (and after Bevill promised that a definitive analysis of coal ash’s danger would be available in two years), the EPA finally wrapped up its coal-ash studies, which determined that coal ash posed “significant risks to human health and the environment when not properly managed.” The agency cited 11 cases where coal ash contaminants were found in ground or surface water at levels that exceeded health standards, as well as dozens of other newly reported cases of water contamination. Communities from Faulkner, Maryland, to Velva, North Dakota, were grappling with the consequences of coal ash. Regulators forced utilities in Wisconsin and Virginia to pay to hook homes up to a public water supply after contaminating their private drinking wells. Beyond these cases, the EPA determined that utilities had installed well networks to monitor groundwater quality at only 38 percent of the nation’s ash ponds and installed protective liners at just 26 percent of them. Given those low percentages and the limited oversight by states, EPA officials recommended tougher coal ash regulations — ones that stopped short of reclassifying coal ash as a hazardous waste.

Medical experts say that over a dozen trace metals in coal ash can lead to health ailments ranging from mild (nausea) to serious (organ damage). The type and extent of health problems can vary greatly depending on the amount of contaminants entering the body, the duration of the consumption and even where the coal was originally mined. Of those dozen toxins, several — including arsenic and hexavalent chromium — are considered to be carcinogenic if consumed even in small amounts over a long period of time. The list of cancers linked to coal ash contaminants include ones in the liver and lungs, prostate and bladder, and stomach and skin.

In 2000, as the EPA proposed tougher coal-ash regulations, Southern Company fought those efforts. Georgia Power, Alabama Power, and Gulf Power were all dues-paying members of the Utility Solid Waste Activities Group, an industry association of over 100 utilities. Led by a lobbyist named Jim Roewer, USWAG had previously recruited power company employees to testify against the hazardous waste designation and attack environmental studies that were being considered by the EPA. (Roewer did not respond to multiple interview requests.) On behalf of Southern Company and other utilities, USWAG lobbyists aggressively pressured the Clinton administration to stop the EPA proposal, citing the billions of dollars it would take to clean up toxins from the ash ponds. They argued against the regulation in letters and in-person meetings. Ultimately, the Clinton administration backed off from the tougher coal ash regulations.

But the risks the EPA tracked remained hidden from the public. During the George W. Bush administration, EPA officials had produced internal reports that showed people who lived close to unlined coal-ash ponds were more susceptible to cancer. The EPA report found that nearby residents had as much as a 1 in 50 lifetime risk of developing cancer from drinking water with high levels of arsenic, one of the most common coal-ash contaminants. That’s 200 times higher than the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health’s recommended risk level for limiting worker exposure to any carcinogen. When environmental advocates tried to obtain those records, officials delayed their release for years; they were made public by the Obama administration only after the Kingston spill.

Georgians rarely heard about problems with Georgia Power’s ash ponds. In 2002, local journalists covered the story of a 4-acre sinkhole at northwest Georgia’s Plant Bowen, which released over 2 million gallons of arsenic-laced ash and water into a nearby creek. From 1988 to 2008, GHN and ProPublica found that Georgia Power had disclosed to state regulators dozens of other unpermitted discharges at its coal plants. The vast majority, which were logged by state environmental officials, were not publicized by those officials or the media.

After chilling images of toxic Tennessee ash circulated in 2008, Obama’s EPA administrator, Lisa Jackson, vowed that environmental disasters like the one in Kingston “should never happen anywhere.” When EPA officials sought further information from the records of coal-ash pond safety inspections after the Kingston spill, Georgia Power initially moved to prevent the release of that information, claiming those records contained trade secrets. The EPA rejected that argument. Ultimately, the EPA found that over a quarter of the country’s 559 coal-ash ponds were rated “poor” in a safety assessment and required remedial action to correct their flaws. (One of Georgia Power’s ash ponds at Plant Hammond was rated poor; most were deemed “satisfactory.”)

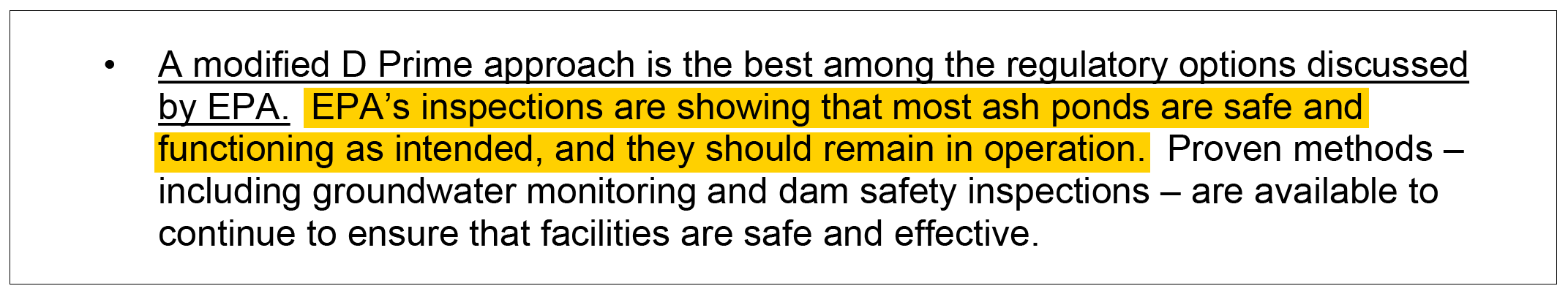

During a 2009 meeting with EPA officials, Southern Company CEO David Ratcliffe and other utility execs urged then-EPA Administrator Jackson not to impose liner mandates for coal-ash ponds. Jackson told the utility execs that she “understands all sides of the argument” regarding coal-ash regulations but did not comment specifically on the issue of liners, according to an EPA readout. (Jackson, who is no longer with the EPA, did not respond to a request for comment.) Southern Company’s top environmental affairs executive, Chris Hobson, followed that 2009 meeting with a letter that claimed its unlined ash ponds were “safe and functioning.”

Five years passed without new regulations. Then, in February 2014, a pipe ruptured at a Duke Energy coal-fired plant, flooding North Carolina’s Dan River with 39,000 tons of ash. The Dan River spill finally pushed the EPA to enact America’s first-ever federal coal-ash regulations in 2015. The rule sought to lower the risk of catastrophic failures, protect groundwater, and outline best practices for shuttering ash ponds. Under those regulations, Georgia Power would be required to publicly disclose the results of groundwater monitoring tests near its ash ponds.

But the industry’s fierce lobbying campaign defanged stronger protections originally proposed by the EPA. Once again, utilities escaped the hazardous waste label for coal ash. Georgia Power could still dump the ash into unlined ponds so long as the utility proved that large amounts of contaminants were not leaking beyond a pond’s edges. Environmentalists criticized the rule for squandering a historic opportunity to pass strict regulations, including mandated liners.

“The coal-ash rule was a compromise,” said Avner Vengosh, professor of earth and ocean sciences at Duke University, who is one of the nation’s leading experts on coal ash. “Instead of declaring it as a hazardous waste, they were reluctant to do so for political reasons.”

In 2011, nine years after Brack’s death (and three years before the EPA finalized the coal-ash rule), Andrea noticed that her grandmother had stopped drinking water from the kitchen tap. She’d started to worry after word had spread that something might be wrong with the groundwater that supplied her drinking well. Suspicions grew that summer, after Georgia Power purchased the 2-acre lot next to the family’s property for $218,750, a stunning price considering the average acre in the area sold for four figures. The property belonged to Gloria Dorsett, Andrea’s great-aunt, the one diagnosed with breast cancer. Georgia Power required that Dorsett sign a nondisparagement agreement, razed her home, and sealed off the drinking well, preventing future testing of its groundwater. (State law requires the utility to seal unused wells within three years to protect against accidents and illegal dumping.)

Andrea couldn’t help but think about all those summer days in her childhood, drinking from the garden hose. After switching to bottled water herself, she searched for news articles that mentioned groundwater contamination near coal plants. She then turned to scientific studies to better understand the effects of coal ash on human health.

From 2014 to 2018, Monroe County had one of Georgia’s highest rates of cancer incidence, at 522 cases per 100,000 people, which was 12 percent higher than the statewide average and 17 percent higher than the national one. Juliette, with 3,000 residents, accounted for about a tenth of Monroe County’s population. Andrea wondered if Juliette’s cancer rate was even higher than Monroe County’s — it would take just 16 new cancer incidences in an average year for Juliette to exceed the county rate. But no formal cancer-cluster study had been conducted to determine if coal-ash toxins had contributed to their sicknesses.

Dr. Alan Lockwood, a neurologist who wrote “The Silent Epidemic: Coal and the Hidden Threat to Health,” says that it’s “really difficult” to establish a link between the health outcomes reported by an individual — or even a single family like the Goolsbys, who’ve had numerous cancer incidences — and trace metals found in groundwater. To establish that link, epidemiologists must study data collected from private wells in an entire community over time and review the medical histories of residents to determine if a place is a cancer hotspot. Because of the costs, time and expertise needed, Lockwood said, “the deck is stacked in favor of the company because of how difficult it is to show a cause-and-effect relationship.”

To prove such a thing in court, residents must rely on deep-pocketed lawyers to fund class-action suits. If all the stars align, a company will be pressured into a settlement. More often than not, big corporations with seemingly endless resources can evade responsibility. Despite the long-shot odds of holding Georgia Power accountable, Andrea felt there was no other choice but to seek answers about the water. To her, the pursuit was not just a question of sickness or health, contaminated or not: It might reveal a greater, unsettling truth about the unintended consequences of a tightknit town placing its faith in the hands of a corporation that pledged to do right by its residents.

In 2013, three of Andrea’s relatives were among more than 100 current and former Monroe County residents who sued Georgia Power, claiming the utility had knowingly released toxins contained in coal ash into the air and groundwater. The lawsuit contended that contaminants from Plant Scherer caused a “loss of potable water supply and increased risk of diseases.” In court filings, Georgia Power denied the claims. But before the case proceeded to discovery, one of the law firms representing the plaintiffs abruptly dropped out, prompting the suit to be dismissed without prejudice in 2014 — a disposition that allowed for the filing of future claims. In a moment of despair, Andrea looked up the email of Erin Brockovich, the environmental activist who had uncovered evidence that Pacific Gas and Electric Company had contaminated drinking wells with hexavalent chromium in Hinkley, California, a tiny town more than 100 miles northeast of Los Angeles. Hundreds of Hinkley residents alleged that tainted drinking water had caused miscarriages, cancers, and a scourge of chronic illnesses. After a three-year legal battle, PG&E agreed to pay a record-setting $333 million settlement in private arbitration. Andrea pasted into the email a news article about Juliette residents’ fears over contamination, followed by a brief, urgent message.

“What can we do about this?” Goolsby wrote.

Brockovich promised to look into the matter. But when Goolsby didn’t immediately hear back, her family looked for help closer to home. (Brockovich did not respond to a request for comment.) In the summer of 2016, Andrea’s father, Mark — who’d left Georgia Power the mid-’90s to become a funeral home director — learned of an environmental nonprofit called the Altamaha Riverkeeper that had called for his former employer to safely close its ash ponds. During a conversation with the organization’s executive director, Jen Hilburn, Mark Goolsby explained his concerns about potential groundwater contamination along Luther Smith Road. In response, Hilburn told a story about nearby Lake Sinclair in Milledgeville. Earlier that year, heavy rains had threatened to send water pouring over the top of an ash pond’s berm at Plant Branch, which could have caused a major breach. Hilburn received an anonymous tip that the plant had pumped wastewater into the lake, avoiding a violation of its permit but polluting that 24-square-mile body of water. She flew a camera drone overhead, sent her photos to state officials, and publicized the risks. Residents and lawmakers successfully pressured Georgia Power to move the ash out of the plant’s pond and into a lined landfill. (Georgia Power said in a statement that the decision was about “more than compliance” and reflected its commitment to “protecting water quality every step of the way.”)

One afternoon that August, Hilburn traveled up Luther Smith Road to the Goolsby family home. Mark showed her the dying trees and the surface water on his property that had a sheen of oil. After walking over to a small roofed structure that housed the well that supplied water to Goolsby’s taps, Hilburn pulled on gloves, broke the seal of a sterile plastic bottle, and filled it with water. She collected several bottles and shipped them to a lab in North Carolina. The lab would determine if the contaminants found in Goolsby’s well were the same ones found in coal ash — and whether they were present at high enough levels to be harmful.

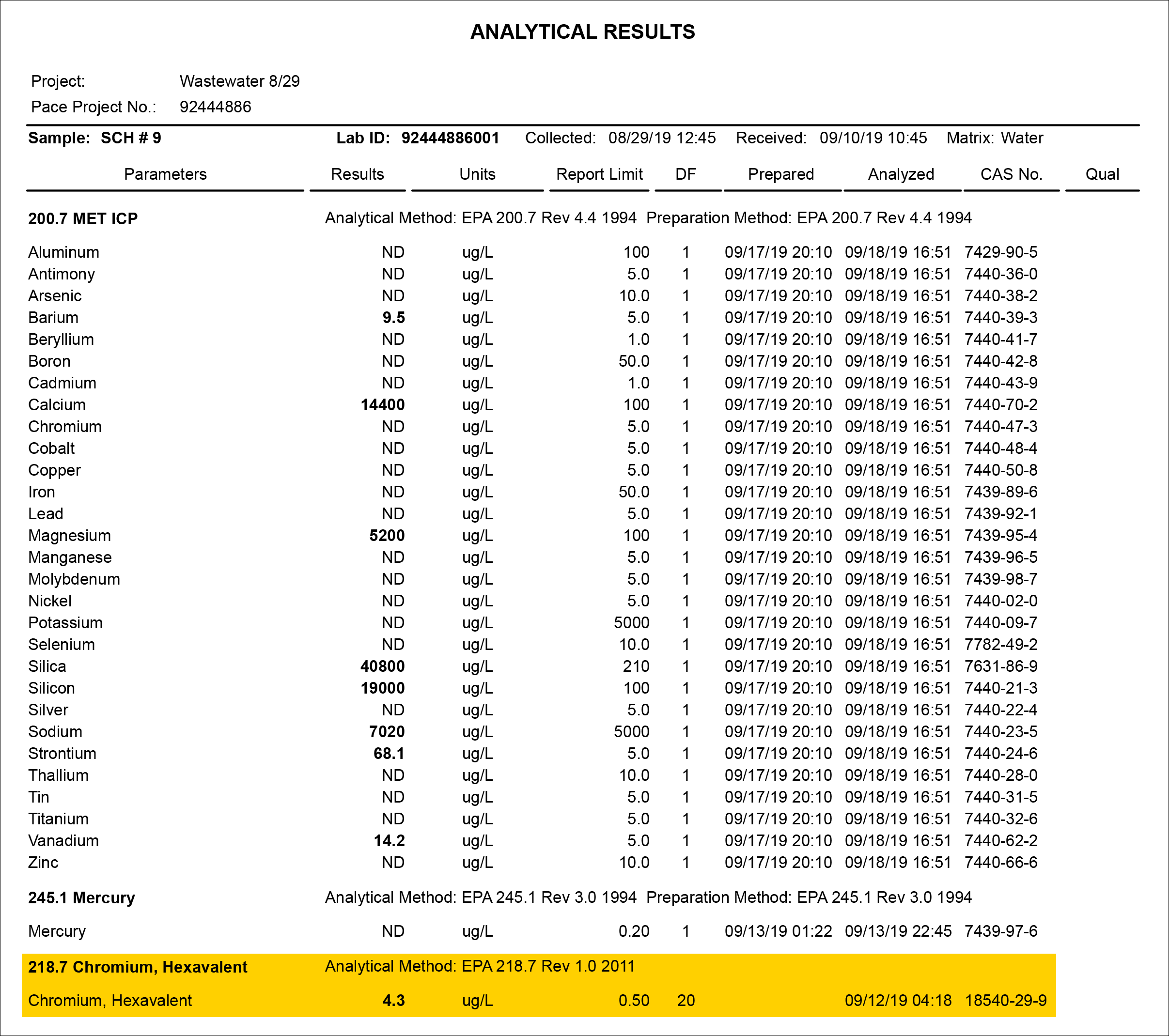

When the results came back a couple weeks later, Hilburn called Goolsby to explain that the well water sample confirmed the presence of several heavy metals such as boron, considered one of the DNA fingerprints of coal ash, and cobalt, a trace metal confirmed to be leaking out of Scherer’s ash pond at levels that exceeded federal groundwater-protection standards. She also said that the samples contained worrisome levels of hexavalent chromium: 2.3 parts per billion, 33 times higher than what North Carolina public health guidelines deem safe and 115 times higher than what California ones do. (California and North Carolina are the only two states to establish public health guidelines for hexavalent chromium in water.)

Georgia does not regulate hexavalent chromium, specifically, in water — only the broader category of “chromium,” which includes both chromium III, a naturally occurring trace metal, and hexavalent chromium, which can be naturally occurring or produced by industrial processes. But while relatively high levels of chromium III is considered safe in drinking water, experts say hexavalent chromium can be dangerous at much lower levels. Some scientists warn that hexavalent chromium, not chromium III, can lead to a higher risk of cancer. Georgia’s local public health departments offer a $122 well test that can detect a limited number of toxins, but not hexavalent chromium. If someone can’t afford to pay more for a private lab to test for that toxin, former EPA official Betsy Southerland says they’re “totally unprotected.”

In the fall of 2016, weeks after Mark Goolsby received the test results from his well water, Georgia Power purchased a string of properties along Luther Smith Road, part of a quiet buying spree in which the company ultimately paid more than $15 million for nearly 1,900 acres of land near five of its 12 coal-fired power plant sites, according to a previous investigation by Georgia Health News and ProPublica. A year later, in 2017, Andrea’s grandmother passed away after a stroke, and Andrea noticed the company had erected “no trespassing” signs along Luther Smith Road and knocked down more homes. More than four decades after attorney Tommy Malone pressed Brack Goolsby to sell most of his family’s land, Georgia Power returned with another offer — this time for the last of their property and the home that had belonged to the Goolsbys for more than 150 years. The company, which still wielded the power of eminent domain, said in a statement that its purchases of land near Plant Scherer would reduce the “short- and long-term inconvenience for our neighbors” during the process of shutting down the nearby ash pond.

On a windy day in March 2019, Andrea Goolsby, then 31, pulled down a gravel driveway toward the white two-story house on Luther Smith Road. Her father and uncle were just days away from handing it over. The terms of the sale prevented them from speaking publicly about the well tests that found hexavalent chromium in their drinking water. (Citing a nondisparagement agreement, Mark Goolsby declined to speak for this story. A spokesman for Georgia Power noted that confidentiality clauses are routinely inserted in its contracts but declined to comment regarding any purchases of individual properties off Luther Smith Road.)

As she walked inside, memories flooded back: the taste of her grandmother’s biscuit dough, the smell of fresh-tilled dirt in the garden, the sound of the blues playing from her daddy’s truck. She had recently helped her father clear out the house, sorting through her late grandmother’s old letters, church bulletins and photographs. She’d even stripped century-old wood off the walls of a bedroom in hopes of repurposing it someday. Tears fell past her straight blonde hair as she stepped into each room one final time. She felt like her grandparents had died once again.

“I had to say goodbye to a place where my son, nieces and nephews won’t be able to experience,” Andrea wrote in her journal that day. “I had to say goodbye to a piece of my heart.”

Two weeks after Andrea’s final visit to her family home, Mark Berry faced one of his toughest challenges as Georgia Power’s top environmental lobbyist: persuading five fiscally conservative energy regulators to allow his employer to offload more than $7 billion in coal-ash cleanup costs onto its customers.

Georgia Power, along with the Public Service Commission, has fought GHN and ProPublica’s attempts to obtain information about how much money the company is saving by not adopting the more protective measure of moving all of its coal ash into lined disposal sites. Last year at a town hall meeting in Monroe County, PSC commissioner Tim Echols said that at Plant Scherer alone, moving millions of tons of ash out of its current pond and into a disposal site with a protective liner would cost $1 billion. (Georgia Power did not dispute Echols’ estimate when asked if it’s accurate.) Industry cost estimates obtained by GHN and ProPublica indicate that Georgia Power could have originally installed a liner at Scherer back in the early 1980s for $95 million or less — $270 million in 2020 dollars, far cheaper than the $1 billion it would take to fully fix the problem today.

Getting approval for the cheaper plan from the five energy regulators on the state’s Public Service Commission would not be Georgia Power’s final hurdle. Even with the PSC’s rubber stamp, state environmental officials could reject the company’s plans to keep dry ash in unlined ponds at Scherer and five other plants. That would mean that Georgia Power’s $7.3 billion price tag could skyrocket to over $10 billion, potentially lowering the chances that the company would be able to get its customers to pick up the full bill. (A year after Berry took the stand, Georgia Power would disclose in a filing that its ash pond cleanup cost estimates increased by 11 percent to $8.1 billion.) PSC Commissioner Tricia Pridemore said the agency recently hired a consultant to review Georgia Power’s future coal-ash expenses. The other four commissioners declined to comment.

In the spring of 2019, the EPA’s administrator, former coal lobbyist Andrew Wheeler, authorized Georgia to become one of America’s only states to take over the process of approving how utilities could clean up their ash ponds. Left to work with the state’s cash-strapped environmental agency (the EPD), Georgia Power pressured regulators to narrowly interpret the coal-ash rule in a way that would increase the chances of leaving its waste in unlined ponds, according to records obtained by GHN and ProPublica. Georgia Power did not respond to questions about lobbying tactics. But in his 2019 PSC testimony, Berry said Georgia Power is “actively involved in both federal and state rulemaking.” EPD spokesperson Kevin Chambers, who did not make any agency officials available for an interview, said in a statement that the EPD “does not provide deferential treatment” to Georgia Power.

In a closed-door meeting in early 2020, EPD Land Branch Chief Chuck Mueller met with a small group of Juliette residents, including Andrea and several members of the Goolsby family. Mueller explained that if the company could show its contaminants had not migrated beyond its property lines, the company would satisfy the state’s environmental requirements, according to a recording of the meeting obtained by GHN and ProPublica.

One Juliette resident, John Dupree, asked Mueller why the EPD hadn’t independently tested nearby Juliette residents’ wells for the presence of contaminants. Dupree recently tested his drinking well, finding levels of hexavalent chromium above the health standards set by California and North Carolina. He was concerned that coal ash would move off-site for years to come, perpetually jeopardizing his family’s drinking water.

“What I’ve got to determine is, is it coming from the ash pond, or is it naturally occurring, or is it from another source?” Mueller told the residents. “I don’t know.”

Berry assured residents that Georgia Power is “working hard to make things better.” But what he left unsaid was that Georgia Power’s recent purchase of over 1,000 acres of land near Scherer’s coal-ash pond would extend its property lines and limit its liability. Simply reducing the number of private wells in operation near the ash pond is far cheaper than installing a liner that would prevent further spread of contaminants.

After the conversation meandered into technical jargon, one of Andrea’s neighbors, Karl Cass — whose son and niece had survived two different kinds of childhood cancer — directed the conversation back toward Berry.

“I appreciate your commitment, based on what you’ve shared, that you want to do the right thing — did I hear that correctly?” Cass asked Berry.

“Yes sir, you did hear that correctly,” Berry said.

“I appreciate your commitment,” Cass continued. “Why the resistance on the liners?”

Berry said the company had “really studied” this site and concluded that burying the waste in an unlined pond was a viable option to comply with state regulations. The company’s groundwater modeling predicted that contaminants wouldn’t move out enough to warrant a liner. Because of that, he said, the residents didn’t need to worry. Georgia Power declined to comment on Berry’s remarks.

“If something is happening, EPD is going to ask us to fix it and we’re going to fix it,” Berry said.

In the months after Georgia Power purchased the Goolsby home, more family members got sick or died. One of Andrea’s cousins, Gloria Hammond, believed the prostate cancer that recently had killed her husband, Cason, was linked to toxins in the water. Two of Andrea’s other relatives, a retired grocery store owner named Tony Bowdoin and car bumper repairman named Mike Pless, were diagnosed shortly thereafter with colon and throat cancer, respectively. Few of the cancer-stricken family members were related by blood to the Goolsbys — some had married into the family — which, to Andrea, ruled out the possibility that the cancers were caused by a genetic predisposition. All three of her recently diagnosed family members lived close to Plant Scherer’s ash pond. The Altamaha Riverkeeper, now overseen by a former paratrooper named Fletcher Sams, had recently tested all three of their homes’ wells. Each one contained hexavalent chromium levels between 30 and 140 times higher than drinking-water guidelines in North Carolina, and between 100 and 490 times higher than those in California.

In early 2020, residents’ concerns about Plant Scherer’s coal-ash pond prompted a bill from Democratic state lawmakers that would force all of Georgia’s coal ash to be moved into lined disposal sites. One night in February 2020, the same month as the closed-door meeting with Berry, Andrea joined Hammond, Bowdoin, Pless, and dozens of other Juliette residents inside a tiny Presbyterian church with stained-glass windows. They’d gathered to learn more about the ongoing groundwater test campaign conducted by the Altamaha Riverkeeper. For months, Sams had steered his red pickup truck down driveways near Plant Scherer and to homes farther away from the plant, collecting water samples from anyone who’d asked for their well to be tested. Now he was finally revealing the full results of what he’d found so far.

Standing before the crowd, Sams explained that almost all of the more than 30 wells he’d tested so far at homes near Plant Scherer had contained worrisome contaminants often present in coal ash that could be harmful to humans if consumed at high enough levels. The wells closer to Scherer’s ash ponds — including along Luther Smith Road — generally had levels of hexavalent chromium higher than those farther away. Pointing to a projector screen near the altar, Sams showed a Georgia Power filing certifying that parts of the ash pond are so deep that they’re below the water table, which meant those contaminants are in constant contact with the groundwater in the aquifer. He then pulled up an aerial image of Scherer’s ash pond, circled by red dots signifying locations of Georgia Power’s own groundwater monitoring wells where tests had exceeded federal protection standards for cobalt, a trace metal leaking out of Scherer’s ash pond.

Sams then rattled off other coal-ash contaminants that the tests had found, words most residents had only ever heard while studying the periodic table during chemistry class.

Residents had grown visibly uncomfortable by the end of Sams’ presentation. Afterward, some people suggested that Georgia Power should pay for county water lines to be built to their homes so they wouldn’t have to drink from the wells anymore. Hammond, one of the few Luther Smith Road homeowners who refused to sell to the company, said she doubted that would happen; doing so might signify an admission of guilt.

Incredulous, Andrea doubled down on the call for Georgia Power to fix the problem. She said the company was already “purchasing property and paying people hush money” so they would not discuss contamination. (Georgia Power did not respond when asked about Goolsby’s comment.)

At one point, Andrea noticed a man in a suit near the front of the church. When someone shouted a question his way, he walked toward the altar to grab the microphone from Sams. The man, PSC Commissioner Echols, explained that he and his colleagues had approved Georgia Power’s request to pass $7.3 billion in ash pond cleanup costs on to customers, adding that “we authorized a lot of money — billions of dollars.”

Listening closely, Andrea grew outraged as Echols — who had voted two months earlier to allow Georgia Power to start collecting money from its customers — shifted the responsibility for reining in Georgia Power to EPD, inaccurately claiming that the environmental agency had the sole authority to stop the company’s unlined pond proposal. (The Sierra Club’s Georgia chapter would later sue the PSC for unlawfully granting the bill surcharge; the company is approved to recoup a first round of $525 million, though it is expected to return to PSC for permission to recover the remainder of the cleanup costs in future rounds. The case could soon go before the Georgia Court of Appeals. Echols declined to answer GHN and ProPublica’s questions, but said in a brief statement, “I am confident we are on the right track.”)

“I wasn’t even born when the problem started, but I have to pay for this mess?” Andrea later said. “It’s hypocritical. They’re the ones doing this, but we have to pay for it, when it would have cost a lot less to do it right the first time or fix it when they knew it was a problem.”

As COVID-19 spread across Georgia, Berry’s team submitted more than 25,000 pages of filings to the EPD to prove how its plan to bury 48 million tons of coal ash in ponds without a protective liner was, in fact, legal and safe. But in corporate filings dated as recently as 2020, Georgia Power acknowledged that Plant Scherer’s ash pond was susceptible to a catastrophic dam failure that could mirror the Kingston spill, potentially sending a wave of ash toward homes, injuring or killing Juliette residents, and contaminating a span of at least 15 miles of the nearby Ocmulgee River. Parts of the ash pond had grown unstable enough that, in 2017, one contractor nearly died after a sinkhole larger than a basketball court suddenly opened up in the pond, causing part of the shoreline to collapse, according to photos of the incident and eyewitness accounts. (Georgia Power did not respond when asked about the sinkhole.)

On top of that, the company faced a growing number of hurdles related to coal-ash contaminants. Georgia Power had to notify a homeowner near Plant McManus in Brunswick of its discovery of levels of arsenic in groundwater that exceed federal and state safety limits. During a recent legislative hearing, state Rep. Mary Frances Williams told one of Berry’s deputies that she was “concerned” to discover contaminants had migrated off-site from Plant McDonough’s ash pond over to property owned by Cobb County in suburban Atlanta. “I’m not clear how you can prevent that from happening without liners,” she told the Georgia Power lobbyist.

Plant Scherer, however, posed the biggest challenge for Georgia Power. EPD scientists said last year that they would need more information before the agency could allow the company to move ahead with leaving dry ash in Scherer’s unlined pond. Georgia Power had disclosed to EPD the data from several dozen groundwater monitoring wells near Scherer, some of which detected the presence of contaminants often found in ash ponds at levels higher than groundwater-protection standards. The data also showed that contaminants were migrating toward the properties the company had purchased on Luther Smith Road. The EPD is now seeking to determine the speed at which groundwater flowed through and under Scherer’s ash pond and to what degree the contaminants posed a threat to remaining neighbors. (Chambers, the EPD spokesperson, said permits to leave coal ash in unlined ponds will not be issued to Georgia Power if its plans fail to comply with the coal-ash rule.)

The company downplayed the concerns from outside experts. Back in 2019, Berry testified that “advanced engineering methods” would allow Georgia Power to clean up its ash pond at Scherer in a way that complies with environmental regulations, but he has refused to disclose the methods because the company claims they are confidential. In January, Georgia Power submitted filings that claimed further risk evaluations of groundwater were no longer warranted because the ash pond’s contaminants “are not expected to pose a risk to human health or the environment.”

In another recent filing, Georgia Power claimed that contaminants such as hexavalent chromium at Plant Scherer come from “naturally occurring” sources instead of its operations. Researchers in North Carolina, led by Vengosh of Duke University, have found that high levels of hexavalent chromium found in drinking wells in the central part of that state are in fact naturally occurring. (A similar study has not been conducted to determine the source of the hexavalent chromium in Juliette’s drinking water wells.) On the other hand, Vengosh also has conducted research showing that ash from Wyoming-sourced Powder River Basin coal — the coal that Georgia Power uses at Plant Scherer — contains high levels of hexavalent chromium. Last year Vengosh wrote in an email to Monroe County officials that “even if the hexavalent chromium found in drinking water wells is not derived from coal ash contamination,” other coal ash metals could pose a “constant risk” to homeowners’ drinking water.

Residents’ fear of that constant risk has revived a legal battle against Georgia Power. Brian Adams, the Macon attorney behind the lawsuit that fizzled in 2014, found a powerful new partner in Atlanta attorney Stacey Evans. A state lawmaker who once ran for governor, Evans was looking for her next big case after winning a $495 million whistleblower settlement against DaVita, an international dialysis chain. Last July, Evans and Adams filed a new lawsuit on behalf of 45 residents who alleged that Plant Scherer is “poisoning” their community’s water. Their claims extend beyond those of the previous case: The lawsuit alleges that Georgia Power not only constructed and operated Plant Scherer in a way that led to contaminated drinking water, but also that the company built a network of monitoring wells at an elevation so high that their groundwater testing “evades representative results.” Georgia Power has denied those allegations in court filings.

One of the plaintiffs, Andrea’s cousin Tony Bowdoin, said last summer that he’s seeking damages to offset the six-figure costs of treatment for Stage IV colon cancer. Another plaintiff, Karl Cass, whose son is a survivor of childhood cancer, hopes a jury trial might deliver clarity in a saga that so far has offered no clear answers.

“I don’t want to see my kids have to fight this fight against Georgia Power,” Cass said. “And I hope their children won’t have to live in fear about what’s happening to their health.”

Asked what would make things right, Andrea explained that the answer is both simple and complicated. Driving around Juliette in the lead-up to the 2020 presidential election, Andrea saw one type of yard sign more than any others. It wasn’t in support of President Donald Trump, as one would have expected in deep-red Monroe County, where 70 percent of voters cast ballots for him last year. It was one with a clear call to action: Georgia Power: Clean up your trASH.

At a hearing expected to be held in late 2021, Andrea intends to urge the EPD to reject Georgia Power’s plans to bury coal-ash waste in unlined ponds. If she and other Georgians get their way, state officials would force the company to submit a new plan to either retrofit the ponds with a liner or move the ash to a lined disposal site and begin the yearslong process of reducing the immediate threat to the groundwater.

Andrea said Georgia Power should also cover the costs of Monroe County’s $16 million project to extend water lines to the homes of about 850 Juliette residents who currently rely on drinking wells. (Those residents still would need to pay — as much as thousands of dollars — to have the line connected to their homes; Andrea says Georgia Power should pay for that, too.) Georgia Power has instead mailed residents packets touting the company’s environmental track record and accusing the Altamaha Riverkeeper of making “false claims” about contamination. To find the truth, Andrea said, there should finally be a cancer-cluster study to figure out whether coal-ash contaminants are linked to more than 40 cancer cases compiled by her and others in the community.

The more complicated solution, as Andrea explained, is compensating Juliette residents for “what they lost.” She’s thinking of her cousin, Hammond, who rejected recent offers by the company to buy her land on Luther Smith Road, in part because her well may hold answers to the question of why her husband died. Then there’s Mike Pless, another of her relatives, who, after surgery and two rounds of radiation therapy, has reckoned with his uncertain future and what that might mean for his family. “No easy choices, no guarantees,” he wrote on Facebook. “Welcome to the crucible.”

In late February, Andrea was once again reminded of all she has lost. A mile north of Luther Smith Road, she walked up a gravel path in a black funeral dress, past her grandparents’ tombstones, to find a sunflower-topped wooden casket holding her cousin, Tony Bowdoin, who had just died from colon cancer at age 58. In front of more than 100 mourners, Reverend Mark Goolsby, Andrea’s father, gave a moving eulogy honoring his nephew as an avid hunter and hardworking storekeeper, a serial gift-giver and a morbid joke-teller. Andrea thought of all the death since her grandfather Brack had passed nearly two decades earlier. How much more would her family lose? she wondered. What would Georgia Power’s ultimate cost be?

“They took things families can’t get back,” Andrea said. “There’s no amount of money that can ever give those things back.”