James Parravani came down with flu-like symptoms the day before his daughter’s wedding reception. He had a fever, a headache, and chills. It was Labor Day weekend 2021, and his family thought he might have COVID-19. But a test at an emergency room near his home in Westchester, New York, came back negative.

The ER doctors quickly transferred Parravani to Yale New Haven Hospital in Connecticut, where he had received a kidney transplant a year prior. The specialists there suspected he might have a kidney or blood infection related to his operation. They gave him a round of antibiotics, but he just kept getting worse.

Parravani, known to friends and family as Jim, took a long, winding road to his daughter’s wedding weekend. He dropped out of high school in Schenectady, New York, before his senior year to focus on other priorities. “Rocktoberfest” — a music festival he and his friends threw in a rented-out motel — occupies a near-mythical place in modern Schenectady history. Parravani eventually earned his GED and attended Syracuse University’s College of Law, where he rose to second in his class.

After marrying his middle school sweetheart in 1986, Parravani graduated from law school, moved to Westchester, and began building a career and a family. But in the ’90s, he learned he had a genetic condition called polycystic kidney disease — an illness that causes cysts to grow on the kidneys and often results in organ failure. After several years of treating his cysts, Parravani’s doctors initiated the laborious process of getting him a transplant. In 2020, about a year before his daughter’s wedding weekend, he finally got one.

Now, his doctors thought this transplanted kidney might be making him sick, though they still didn’t know how. The morning of her reception, Jenny Parravani Davis called her dad at the hospital. She asked him if he wanted her to postpone the festivities. “No, no,” he told her. “Keep going.”

From left: Jim Parravani with his daughter, Jenny, as a toddler. Father and daughter on Jenny’s prom night. Courtesy of Jenny Parravani Davis

That was the last lucid conversation Davis ever had with her father. The next day, she got a call from her mother. Parravani was deteriorating — fast.

“He got on the phone and he was really disoriented, he couldn’t form words,” Davis said. “I remember saying ‘Hi, I love you,’ and he just said, ‘Don’t cry,’ and everything after that was incoherent.” Parravani was intubated that same day.

The doctors ran dozens of tests and put Parravani on multiple courses of strong antibiotics to treat the infection. It was only when they conducted a spinal tap — about a week after Parravani’s initial admission — that they discovered the true culprit: West Nile virus was present in his cerebrospinal fluid. The disease had spread to his brain and was making it swell. (Yale New Haven Hospital declined to comment on Parravani’s care.)

For seven months, as Parravani slipped in and out of comas, the doctors tried to beat back the virus with intravenous fluids, pain medication, and oxygen. At one point, it looked like Parravani might pull through. He was nodding and trying to communicate with his family around his breathing tube. The doctors reduced the oxygen flowing through his ventilator, and he breathed on his own. But in March 2022, Parravani began to decline again. On April 13, Parravani died in hospice care. He was 59 years old.

West Nile has been the most common mosquito-borne illness in North America for more than two decades. States in the Great Plains and western U.S. typically report the highest number of cases, though outbreaks have happened in nearly every state in the continental U.S. The disease has killed more than 2,300 people since it first arrived here, and the number of people affected by the virus every year is poised to rise.

As climate change extends warm seasons and spurs heavier rainstorms, the scope and prevalence of West Nile virus is shifting, too. Warmer, wetter conditions allow mosquitoes to develop more quickly, stay active beyond the traditional confines of summer, and breed more times in a given year. Birds, which host West Nile virus and pass it onto mosquitoes that bite them, are adjusting their migration patterns in response to the melding seasons.

The confluence of these two trends could have serious consequences for human beings. West Nile virus, a recent study said, “underlines once again that the health of animals, humans, and the environment is deeply intertwined.” In the past few years, Colorado and Arizona recorded outbreaks of the virus that killed scores of people in each state. Parts of California and Wyoming also reported unusually high cases of the disease. Meanwhile, Nevada, Illinois, and New York registered above-average or record-breaking numbers of West Nile-infected mosquitoes and mosquito activity.

“Overall, the evidence points to higher temperatures resulting in more bird-mosquito transmission and more what we call spillover infections to people,” said Scott Weaver, chair of the department of microbiology and immunology at the University of Texas Medical Branch.

West Nile virus typically leaves young, healthy individuals unscathed. Only 1 in 5 people who contract it develop symptoms, which can include fever, headache, joint pain, diarrhea, and other signs of illness that often resemble the flu.

There is no cure for West Nile virus; the immune system must fight it off on its own. That’s why elderly people and those with preexisting conditions, such as cancer, diabetes, and kidney disease, are at much higher risk of developing the severe form of the disease. So are organ transplant recipients, who take immunosuppressants for their entire lives to ensure the body does not reject the organ.

About 1 in 150 people who get West Nile develop the worst form of the illness, in which the virus attacks the central nervous system. For 10 percent of these patients — including Parravani — encephalitis or meningitis, swelling of the tissues around the brain and spinal cord respectively, leads to death.

Because only a sliver of infected people get seriously sick, the impact of West Nile virus on the public hinges on the number of people who contract the disease. Some years, the number of infections detected in the U.S. approaches 10,000. Other years, there are fewer than 1,000 reported cases. The number depends in large part on environmental conditions — how much rain fell, how warm or cold the spring or fall was — in addition to bird migration patterns and human behavior.

“It’s a rare event that any given mosquito bites a bird and then survives long enough to bite a human” and transmit West Nile virus, said Shannon LaDeau, a disease ecologist at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies. But as with COVID-19, the size of the denominator is crucial. “When you have millions of mosquitoes, that rare event happens more frequently.” LaDeau said.

Parravani’s illness wasn’t the first case of West Nile to stump medical professionals in the U.S. In August 1999, people in the New York City metropolitan area started becoming severely ill with encephalitis. The patients had previously been healthy and reported being outside in the days leading up to their illness. The New York City Department of Public Health suspected a disease spread by mosquitoes was behind the outbreak and immediately launched an investigation.

In the months before the outbreak, researchers in New York had detected an unfamiliar type of single-stranded RNA virus in some of North America’s wild birds. Birds of prey and members of the crow family, in particular, were dying in unusually high numbers. Four weeks after the people in New York got sick, the chief pathologist at the Bronx Zoo connected the dots and sounded the alarm. The birds were infected with West Nile virus, named after the district in northern Uganda where the disease was first isolated in a human more than half a century earlier. And West Nile, public health authorities eventually confirmed, was what was making New Yorkers sick.

By the end of the summer, 59 people had been hospitalized with West Nile virus. Seven died.

West Nile had been known for decades to cause fever, vomiting, headache, and rashes. Epidemics in the Middle East in the early 1950s helped researchers confirm that the Culex genus of mosquito — dawn and dusk biters that prefer to feed on birds — were the primary vector, or carrier, of the disease. Outbreaks of varying severity cropped up all over the world — in France, India, Israel, Italy, Morocco, Romania, Russia, South Africa, Spain, and Tunisia. But it wasn’t until 1999 that researchers understood that migratory birds could spread the virus from one hemisphere to another.

Once public health officials learned what was behind the encephalitis outbreak in New York, they sprayed pesticide and larvicide around the city to kill mosquitoes. But the disease couldn’t be eradicated. Within three years, birds had carried it from coast to coast and throughout much of Canada.

The public health response to West Nile virus in the U.S. since the turn of the century has been punctuated by successes and setbacks. Every few years, when environmental conditions allow Culex populations to boom, cases careen out of control and hundreds of people die. States and cities often belatedly deploy weapons from a limited arsenal — pesticide-spraying and public awareness campaigns — to keep the disease in check. After a boom year, the next one often brings a different cocktail of environmental conditions, and the disease has a much smaller impact on public health.

“There are many things that go into what causes the circulation of West Nile,” said J. Erin Staples, a medical epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC. “And that makes it very difficult for us to predict.”

The unpredictability of the virus is part of what explains the lackluster response by states and the federal government to the threat of West Nile. No vaccine or cure exists, and funding for research on the disease is low, despite the fact that the virus has been claiming lives in North America for a quarter of a century. “Although West Nile virus continues to cause significant morbidity and mortality at great cost, funding and research have declined in recent years,” a 2021 study said. The National Institutes of Health directed $67 million to West Nile research between 2000 and 2019 — less than a tenth of the $900 million it dedicated to research on Zika, a mosquito-borne illness that never gained a foothold in the U.S., in the same period.

Experts warn that climate change is creating more opportunities for West Nile to spread.

Culex mosquitoes thrive in temperate, wet weather. Like other mosquitoes, they lay their eggs in standing pools of water. The eggs can’t survive below about 45 degrees Fahrenheit, but as temperatures get warmer from there, the time between hatching and reproducing gets shorter. The mosquitoes’ ideal temperature for survival ranges from 68 to 82 degrees Fahrenheit, depending on the precise species, but one Culex species can spread West Nile when it’s anywhere between 57 and 94 degrees F outside.

As temperatures rise and make fall, winter, and spring milder, Culex mosquitoes will have more chances to reproduce and spread West Nile in places that didn’t used to see so many mosquitoes. Meanwhile, because a warmer atmosphere holds more water, extreme rain events are getting more common — and that means more standing water for mosquitoes to breed in.

In New York, where winters are warming three times faster than summers, mosquitoes are now active deep into the month of November. A few decades ago, an adult mosquito flying around past the middle of October would have been highly unusual. “We are starting to see and will continue to see shifts in the range” of West Nile virus, said Laura Harrington, an entomology professor at Cornell University, “and shifts in some of the avian hosts that are most important.”

Climate change also pushes birds into new areas, because of weather changes and adjustments in where and when different types of plants and trees grow and bloom. “There are changes to the habitat where birds migrate to breed every year in the Northern Hemisphere,” said Weaver, the University of Texas microbiologist. “And just the temperature itself may have an impact on migration.” As birds enter new habitats, they have the potential to bring West Nile with them.

There’s already evidence that climate change is fueling West Nile outbreaks. In 2021, Maricopa County, Arizona, got an unusual amount of rain — 6.6 inches between June and September, compared to the 2.2 inches it usually gets during that period. That summer, Maricopa County experienced a historic surge of West Nile virus — the worst outbreak in a U.S. county since the disease arrived 25 years ago. Roughly 1,500 people were diagnosed, 1,014 were hospitalized, and 101 people died. The previous year, the number of recorded cases in the region was in the single digits.

A determining factor in the outbreak, Staples said, was the unusual amount of rain. It led to “an unprecedented increase in the mosquitoes and the ability of that virus to then spread to people.” Arizona is projected to get more bouts of extreme rainfall as the planet warms.

To prevent West Nile outbreaks, public health officials must monitor mosquitoes and birds for the virus. But the behavior of mosquitoes makes surveillance complicated — trickier even than tracking other vectors of disease, such as ticks. Unlike ticks, which stay more or less put, mosquitoes can travel a mile or two in any direction. That means public health agencies must launch an expensive and time-consuming hunt for the bugs, using field tests, maps, and guesswork to figure out where mosquitoes are hiding. Birds are mobile, too, and that further complicates efforts to track, map, and control the disease.

Even accounting for these challenges, epidemiologists say too few states are deploying sufficient effort and resources to make sure that they are able to predict and respond to outbreaks of West Nile virus. “We still are using the same vector control and the messaging to use your insect repellant that we were using 25 years ago,” Staples said.

Some states are doing a better job than others. Massachusetts and New York, among the most aggressive states in the nation when it comes to tracking West Nile virus, test mosquito breeding sites and birds regularly and, when positives come back, use that information to inform the public. After Parravani’s spinal tap revealed that he had West Nile, the Westchester County Health Department went to his house and conducted a sweep of the property. County public health officials drained pools of standing water in the backyard where the mosquitoes had likely bred, and they encouraged nearby residents to do the same on their own properties.

“In some places there’s a very clear link that guides when you test and what you test for,” LaDeau said. But “mosquito surveillance is not the norm across all regions, and it’s not standardized among even regions within a state.”

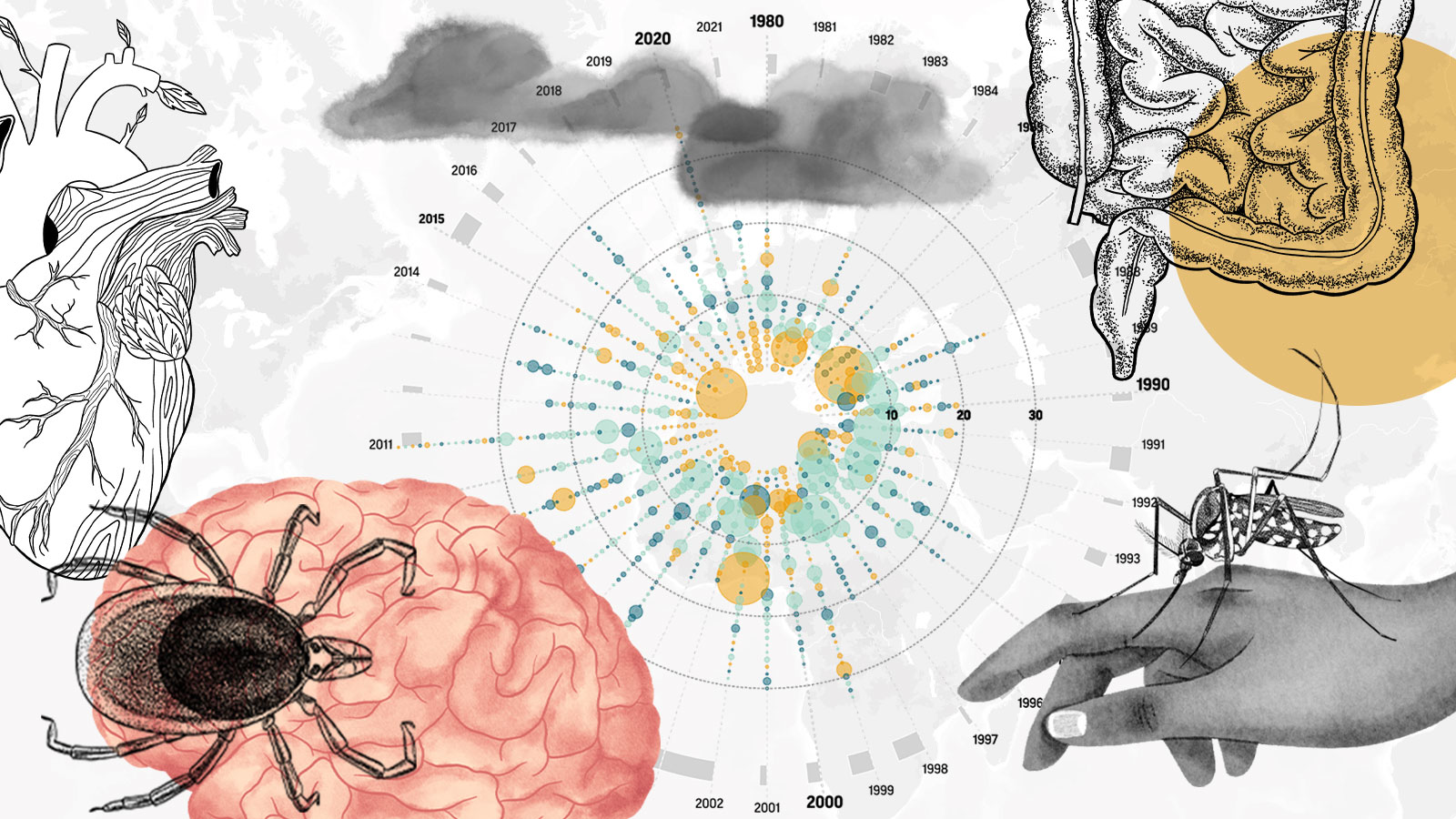

As climate change loads the dice in favor of mosquitoes, West Nile is not the only infectious illness in flux. The number of cases of vector-borne disease in the U.S. have more than doubled since 2001. Some of that increase can be attributed to better disease awareness among physicians and the public, and an uptick in testing as a result. But there are also examples of diseases bursting out of the regions where they have historically been found, which may be an indication that changes in the environment are coaxing carriers of disease into new places.

In 2023, the U.S. saw the first-ever cases of locally transmitted dengue fever in Southern California and unusual cases of locally acquired malaria in Texas, Florida, and Maryland. When a mosquito imparts West Nile virus to a human, the transmission of the virus stops there. An infectious human cannot infect a mosquito with the virus. That’s not the case for dengue and malaria, which makes the spread of those diseases potentially far more dangerous.

Many studies show that infectious diseases will take a larger toll on public health across North America as we make our way deeper into the 21st century. “More Americans are at risk than ever before,” Christopher Braden, the acting director of the CDC’s Center for Emerging and Infectious Zoonotic Diseases, warned in 2022.

If West Nile virus, the nation’s most common mosquito-borne illness, is a test for how the U.S. will weather the coming influx of vector-borne disease, then the country is in bad shape. “We don’t have very good tools to control it and prevent human illness,” Harrington said.

For now, however, those who have been personally impacted by mosquito-borne illnesses are arming themselves with DEET and ringing the alarm. Until recently, Jenny Parravani Davis worked as a communications manager for the Wilderness Society, a land conservation organization that advocates for better protection of the nation’s remaining wild places. The climate change reports that the Wilderness Society puts out generally include top-line findings about the ways in which climate change will erode human health as temperatures rise. But her father’s death, Davis said, drove home just how interconnected these issues really are.

“I started to connect the dots and see the bigger picture,” she said. Her backyard in Virginia collects a lot of water, especially in recent years, as back-to-back record-setting rain events have flooded the state. “I don’t think anyone would blame me, but I’ve developed this neurosis where anytime I scratch a mosquito bite I’m like, ‘Could this be the thing that kills me today?’” she said. “I’ve seen what happens when we don’t pay attention to these things.”

Correction: This story originally misstated Jenny Parravani Davis’ first name.