This story is part of The Human Cost of Conservation, a Grist series on Indigenous rights and protected areas. It was supported by The Pulitzer Center, and is published in partnership with Indian Country Today.

On the morning of July 27, 2022, a small coalition of Shipibo fishers and local farmers living inside a protected area in the Peruvian Amazon steered their boats across a still and glittering lake. They were bound for the town of Junín Pablo, where the regional government had installed a guard post several years prior as a base from which to monitor the area. Upon arrival, they set up camp along the shore beside the offices, with signs reading “No more corruption” and “Don’t fine us for defending our rights.” Over the course of a week, hundreds of people joined from the surrounding towns to peacefully demand the exit of the park administration.

“It was the only way to get anyone to listen,” said Jeremías Cruz Nunta, a member of the Shipibo-Konibo Indigenous community and head of the Indigenous and Peasant Defense Front for Imiría and Cauya Lakes, a committee formed to protect the local waters. Since the toma, or the taking of the post, nine months ago, the group has monitored the entrance to the lagoon with a rotating shift of guards to restrict the entry of government officials. “We had to do something drastic to get people to pay attention.”

For years, the Shipibo have protested the protected area, submitting formal complaints to ask that the supreme decree used to establish it be annulled and that the land be given over to the communities to manage. Despite their claims that the park was established illegally, in violation of their territorial rights, the administration had carried on its operations.

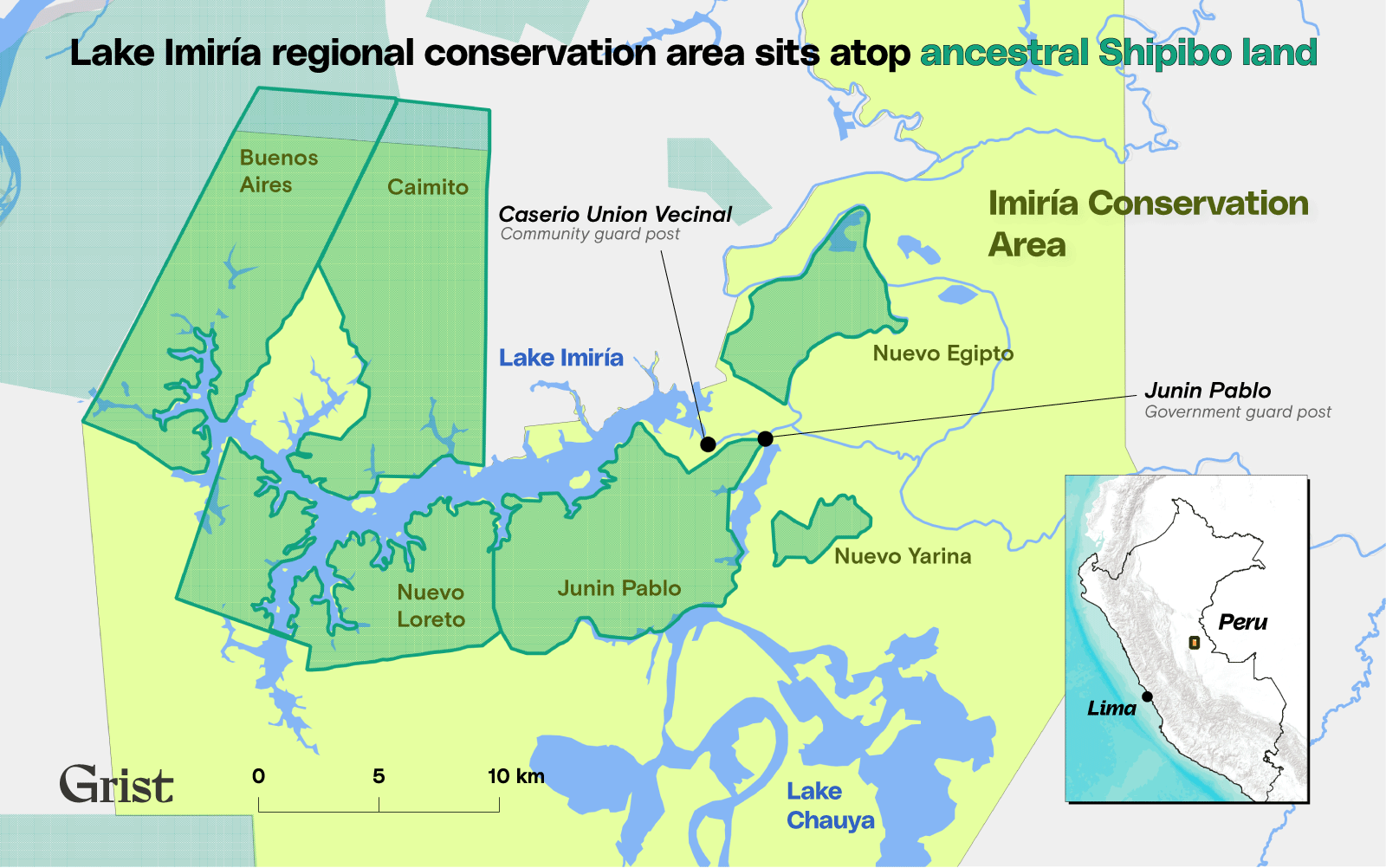

The Ucayali regional government introduced the Lake Imiría regional conservation area, or ACR Imiría (for área de conservación regional), more than a decade ago. The objective was to conserve over 300,000 acres of the Amazonian wetland ecosystem, which had been threatened by illegal logging and fishing, as a park. But the park overlapped with six Indigenous territories, as well as with nine small, untitled hamlets populated by self-described “mestizos” — farmers of mixed descent who migrated to the area from other parts of the Amazon or the Andes Mountains.

Shipibo leaders and their lawyers argue that authorities failed to follow legal protocols of consulting the community and instituted rules that restricted the livelihoods of those within its borders, limiting fishing, farming, and timber harvest to only what families can personally use, but not sell.

“Cutting trees over 10 centimeters is prohibited, as is fishing over 50 kilos,” said Abner Ancon, who lives in Caimito, one of the five titled Indigenous territories that dot the edges of the lake, and whose community has led the resistance against the park. The administration’s efforts to develop replacement income streams through artisanal craft collectives and native fruit cultivation have fallen flat. “In 12 years, there hasn’t been a single benefit for the population,” said Daniel Cruz Nunta, Jeremías’s brother and a Shipibo fisherman who has lived in Caimito all his life.

Meanwhile, the area has increasingly become a focal point for timber poaching, land trafficking, and commercial fishing, contrary to the park administration’s stated conservation aims.

Since the creation of the United States’ national park system in 1872, protected areas like the one at Lake Imiría have been the cornerstone of the global conservation movement, exported around the world and adopted by governments from Kenya to Chile to Indonesia. The model assumes that ecosystems function best in isolation from humans, walling off or severely restricting local peoples’ access to nature in a practice often referred to as “fortress conservation.” But Indigenous communities and their allies have long decried the way this conservation strategy regularly forces local people from the places they have lived in and stewarded, often in a way that protects biodiversity even more effectively, for centuries.

Today, as nations look for land to set aside in the name of climate action and carry out a global agreement to protect 30 percent of the world’s land and waters by 2030, Indigenous communities have been sounding the alarm about an increased risk of dispossession. In Peru — one of the world’s top sellers of forest carbon credits, where over 31 percent of protected areas overlap with Indigenous territories — the ACR Imiría is just one place where Indigenous land rights and state-run conservation have come into conflict.

The Shipibo residents of Caimito talk about the ACR Imiría as another threat to their autonomy and land rights — instead of as an ally against deforestation.

Linda Vigo, a lawyer in the nearby city of Pucallpa who represents the Shipibo communities around Imiría, has documented the steps that the regional government took since it first introduced the ACR in 2010 and again when it approved the park’s first master plan in 2019. She says the park was established illegally, with inadequate and incomplete community consultation, in violation of the United Nations’ Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the International Labor Organization Convention 169, both ratified by Peru.

“If there are 700 people [in a community] and 30 signed, that’s not consent,” said Vigo. “This ordinance has been issued without prior consultation, so we are asking for its annulment.”

The Ucayali River is a primary source of the Amazon River. It forms high in the Andes Mountains of Peru, at the confluence of the Urubamba and Apurímac, and winds its way north for almost 1,000 miles, flowing through dense forest, nature reserves, farmlands, and small towns. Eventually, it joins with the Marañon to form the largest river in the world. Halfway along its route, just before it reaches the port city of Pucallpa, the Ucayali River feeds Lake Imiría, a sparkling lagoon filled with swamp forest islands and abundant diversity of birds and fish.

“The Shipibo have always lived along the banks of Ucayali,” said Ancon. “This is our area.” His grandparents moved to the forests around Imiría from another part of the river in the 1930s and set up Caimito, the first settlement in the area. The community received an official title from the Peruvian government in 1975.

Ancon is standing on his porch along the lake’s shore. It’s election day, last October, and people — Shipibo and their neighbors from all around the area — have come to town to vote. Children jump off boats into the muddy water, grandparents rest in the shade, and fishermen clean their catches along the shore.

But for the serene surroundings — the dense forest at the edge of town, the undeveloped vista across the water — it’s easy to forget that this village of about 200 families, replete with two general stores, a small school, and a health post, sits inside a protected area.

Well before the ACR was created, local communities contended with loggers, commercial fishers, outside farmers, and cocaine cultivators invading their territories or setting up shop in the surrounding forests. The Amazon has a long history of extractive booms, but starting in the 1960s, Peru increasingly pushed the colonization of the jungle through decades of building roads and export hubs, subsidizing the migration of Andean farmers to the region, and handing over contracts to foreign industrial operations.

“Our grandparents found this area uninhabited, full of fish and forest animals,” said Daniel Cruz Nunta. But over the years, pressures on the forests and rivers ramped up. Big boats entered the lake, “failing to discriminate over the size of the fish they harvest,” according to Luis Ojanama Tenazoa, who arrived in 1978 as one of the first inhabitants of Bella Flor, an untitled hamlet on the lake.

In recent decades, Shipibo communities around Lake Imiría, especially Junín Pablo, have dealt with ongoing cocalero, or cocaine farmer, invasions. Farmers associated with cartels as well as others from poor areas of the Andean Mountains, like Ayacucho and Hunacayo, enter, set up camp far from population centers, and clear hundreds of hectares of primary forest.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, in response to local conflicts with commercial fishing boats that increasingly depleted the lake, the government began the process of creating a communal reserve, a national conservation category that designates Indigenous and local peoples as legal co-administrators. But in 2005, as Peru was in the process of decentralizing forestry and environmental management, the authorities recommended that a regional conservation area would be more appropriate and adapted plans to fit the new regime, shrinking the park’s footprint to accommodate overlapping land concessions on the borders of the park. Unlike the communal reserve model, the ACR technically does not require that Indigenous peoples be co-administrators; in their early petitions, the communities asked why the plan had changed.

The early draft management plan for the ACR laid out broadly articulated goals to conserve and restore local ecosystems. But residents say the situation has only gotten worse since the establishment of the protected area.

In some cases, regional officials have actively conspired with industrial farmers inside the park. A 2021 investigation by Mongabay confirmed that since 2017, German Mennonites from Bolivia cleared over 2,470 acres of primary forest in the Masisea district around Lake Imiría; 2,156 of those were inside the titled Shipibo territories of Caimito and Buenos Aires. In a scheme that is currently being investigated by Ucayali’s’s environmental prosecutor, the Ucayali ministry of agriculture sold the land to the Mennonites as agricultural land, knowing that it was primary forest.

Shipibo residents say that the administration has done little to curb illegal fishing and land trafficking, choosing instead to focus on the practices of the Indigenous communities and smallholder farmers.

In 2016, Caimito resident Sorayda Cruz Vesada was on her way to the market in Pucallpa to sell a 33-pound (15-kilogram) paiche, a large fish native to the Amazon, when she was reported by park guards and apprehended by police on a city street. She had planned to sell her catch to buy school supplies for her daughter.

“People were standing around, shouting at the police, coming to my defense,” she said. Nevertheless, she was brought into custody and issued a fine of 1,500 soles, the equivalent of $400. Later, she received a summons to regularly appear at the station in Pucallpa. With her husband ill and unable to help work the farm, fishing was the main form of income for Cruz Vesada, as it is for most Shipibo people. Now, financial and legal complications have thrown her life into a tailspin.

“Enough already with the ACR — it needs to be completely abolished,” said Cruz Vesada, citing some other examples of people who have been fined or arrested for violating park rules in their territories. A family in a neighboring community had four logs of timber confiscated that they were going to sell down the river. Others have been forbidden from expanding their farms.

The park management plan lays out a strategy to compensate for these lost income opportunities through alternative livelihood development, but residents say the projects have been wholly ineffective.

Programs to reforest the area, to grow and sell aguaje and camu camu, native fruits, or to develop what Jeremías Cruz Nunta called “some miniscule program for a small group of women to sell artesanias,” or crafts, failed to bring in income that made a difference in people’s lives — same with programs to raise paiche in enclosed fisheries that never seem to go anywhere.

In 2020, while Shipibo communities were struggling under fishing restrictions that some say made it hard to feed their families, they learned about efforts from the Ucayali Department of Fisheries to develop commercial fishing in Lake Imiría in coordination with the ACR and the United States Agency for International Development, or USAID, which has been working in the area since 2018.

A representative from USAID said the program was part of an effort to formalize fishing in the area, which would allow Shipibo and local communities, as well as outside fishers, to sell fish from the lake legally through government-approved fishing associations. But Shipibo and local residents objected to the fact that the project would allow large fishing associations from Pucallpa to extract quantities of fish that they said were unsustainable and should be protected for local livelihoods which, prior to the ACR, had been more easily and directly accessible. Studies on fish populations that the regional government undertook to support the project have not been made publicly available.

For Caimito residents, the commercial fishing initiative was a tipping point. They decided to reactivate their own Indigenous Guard to protect their forests and waters. “We would paddle out and ask the fishing boats what they were doing in the lake,” said Elvira Pandura Mafaldo, a member of the local guard. Not long after, they were on their way to Junín Pablo to seize the guard post. “Our ancestors always fought for their territory — the communities know how to protect their land.”

Noé Guadalupe, the former head of Ucayali’s environmental authority who finished his term in January, disagrees with the Shipibo’s assessment. “Were it not for the ACR this place would be overrun with cocaleros,” he said in his office in Pucallpa last October.

Guadalupe has a lot of explanations for why conservation and livelihood development have failed within the ACR. The government does not have enough money to hire adequate staff, and the ministries of agriculture, fishing, economic development, and forestry are too siloed and underfunded to address issues like deforestation and public works holistically, he said, while also acknowledging corruption in some areas of the government. (The park administration, under the ministry of the environment, makes reports to the agencies, but does not enforce all the laws itself.)

As for the claim that the ACR was established unlawfully and should be handed back to the communities, he said that’s a decision that would be made over his head. In August, after the toma, or the taking of the guard post, Guadalupe went to a meeting in Caimito and signed a form along with COSHICOX, the Shipibo Konibo Xetebo Council, and ORAU, the overarching Indigenous federation of Ucayali, acknowledging that the communities would retain control of the park offices and take their proposal up with the national government. “There’s no conflict here,” he said. “But they’re making the wrong decision.”

A lack of transparency over where the park’s budget goes has also created a sense that the communities are being swindled. The ACR Imiría’s public-funded budget is a little over $3.5 million for the period of 2019 to 2023, but it has also drawn over $1 million from USAID. USAID spending is not publicly available and the public database that regional officials indicated contains records of the park’s management plan spending was down at the time of publication.

Guadalupe says that of the four pillars of the park’s management plan — infrastructure, capacity building, reforestation, sustainable livelihood development — approximately 60 percent goes to infrastructure for park guards. But residents say the expenses for a small wooden office and five employees don’t seem to add up, and they haven’t seen research or tourism, other components of the plan, happening in the area. “We know money is coming in,” said Jeremías Cruz Nunta. “But where is that money going?”

“The authorities are getting in their name what the communities are supposed to get,” said his brother Daniel.

Roberto Espinoza, a consultant for AIDESEP, the umbrella federation representing Indigenous communities in Peru, described the expansion of protected area conservation in the Amazon since the 1990s as a way for the government to gain access to millions of dollars of international funding in partnership with Western nongovernmental organizations, or NGOs. “When they see that there’s international money for conservation, that’s when the state moves,” said Espinoza. “It’s a very deformed system.”

This same dynamic could still be at play in the fight over who gets to manage Lake Imiría. “I can’t tell you the original reason for setting up the park,” said Matías Pérez Ojeda del Arco of the Forest Peoples Program, a nonprofit that advocates for the rights of forest-dwelling people. “But I can tell you that the reason why [the regional government] wants to hang onto it now has a lot to do with REDD+ money.”

REDD+ — short for Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation — refers to the United Nations mechanism that allows companies and governments of high-polluting nations to offset their carbon emissions by paying for forest conservation, mostly in the tropics. For years, Ucayali has been working on developing a jurisdictional program, where the regional government would be paid to reduce deforestation across their entire area. In the winter of 2021, Ucayali officials signed a deal with the Swiss oil company Mercuria to sell credits through jurisdictional REDD+.

Though the deal is being contested by the national government on the grounds that local governments can’t trade carbon credits before a national accounting program is established, it demonstrates the eagerness on the part of local officials and companies to bring in REDD+ finance. Communities around Lake Imiría say they have been approached by individuals and organizations looking to set up payment for carbon schemes, but so far none exist in the ACR Imiría.

“Everyone is worried about the Amazon, but they don’t give money directly to Indigenous people who have always cared for it,” said Hicler Rodrigues Guimaraes, a member of the Shipibo Indigenous Guard, a new intra-regional organization of Shipibo land defenders that has been supporting the resistance against the ACR as one of its causes. “When I was 16, we didn’t have these problems with deforestation and also with NGOs trying to make money off our forests.”

At a time when rhetoric at the international level emphasizes Indigenous conservation leadership more than ever before, recent research shows that, of global funding specifically earmarked for Indigenous and local communities, only 17 percent actually goes to projects that name a specific Indigenous group.

Pucallpa, the capital city of the Department of Ucayali, sits on the banks of the Ucayali river. A colonial outpost in the 1500s, it functioned as a small, rural trade hub until the arrival of a highway in 1945 turned the settlement into a bustling port city. From the second rubber boom during WWII to the illicit timber and cocaine markets of today, Pucallpa has served as a center from which to exploit the resources of the rainforest. In town, trucks carrying hardwoods from deep within the Amazon rumble along dusty roads past wooden houses and big glass shopping malls on their way toward the highways that connect the jungle to the coast. Tourists come through on their way to ayahuasca retreats with the Shipibo communities in the forest.

From the ports of Pucallpa, there are two ways to get to Caimito. One involves traveling up the Ucayali river and entering the Lake Imiría lagoon from the northeast by boat. The other requires taking one of the twice-daily boats to Masisea, a larger town along the Ucayali, and then driving about an hour into the village.

When the river is low, the route through Masisea is the only option. Along the way, the boat passes lumberyards and floating oil stations; families fishing along the riverbanks; large barges loaded with Amazonian hardwoods like shihuahuaco and pumaquiro; and farmers tending to rice fields in the flood plains.

Once in Masisea, it is an hour’s moto-taxi drive to Caimito, through banana and cacao farms, stretches of second-growth forest, and cleared areas where people from Masisea are raising cattle. About half an hour in, Guimaraes points through a thin veil of trees to something unlike anything else on the landscape. A vast cleared expanse, planted with hundreds of acres of orderly soybean rows. “Mennonites,” he says. From the GPS on his phone, it is clear the deforestation is inside the boundaries of Buenos Aires, one of the Shipibo communities that lies within the ACR Imiría.

In late October, months after taking the guard house, the hamlets and Shipibo communities around Lake Imiría held a meeting to vote on the future of the ACR. The majority supported its elimination.

Álvaro Másquez, a lawyer with the Instituto de Defensa Legal who is representing the Shipibo, thinks there is a strong case to be made that the protected area was established illegally in violation of Peru’s Law of Prior Consultation.

But late last year, a special commission sent by the regional government to study the consultation process for approving the ACR management plan concluded that the regional environmental ministry had followed the protocols as established in law. Soon after, according to Másquez, Peru’s national environmental ministry signaled that because the park was originally established a year before Peru codified its Law of Prior Consultation, the government was not obliged to follow it. But Peru was already bound to respect the right to consultation by international law at the time, says Masquez, and the next step will be the courts.

As the Shipibo fight to get their territories excluded from the park, they don’t want to lose the access to government funding that comes with being a conservation area. Many hope to establish a new type of “Indigenous ecological area,” managed by local communities who could receive state and international funding directly, instead of having it go to park administrators. Másquez is also looking into conservation categories that already exist in the law and could align with the communities’ aims. “We still have to have a dialogue about what the rules would be,” said Jeremías Cruz Nunta. “But we don’t want to impede money from the government.”

The agreement to protect 30 percent of the world’s land and water established at the U.N. Biodiversity Conference in December is set to be implemented through “systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures, recognizing Indigenous and traditional territories.” Some Indigenous groups and advocates lamented that it did not include Indigenous titled lands as their own distinct conservation category. If the Imiría coalition succeeds in petitioning for a complete overhaul in park management, they could establish a model for how “other effective area-based conservation measures” might actually be led by Indigenous peoples as the primary beneficiaries and rights holders. But they have a lot stacked against them, including local NGOs, USAID, tumultuous regional and national politics, and an influx of carbon-credit cash on the horizon, raising the stakes of who owns the forest.

Whether through Congress or the judiciary, Masquez doesn’t think any major legal changes will happen anytime soon. The country is currently in a political crisis. In December, the national Congress was dissolved and the President of the Republic, a teacher from the Andes with peasant farmer roots, was ousted. People long outraged with Peru’s corrupt political class took to the streets, rioting. Protests are ongoing, with the death toll over 60 amid accusations against the army for using excessive force, especially in the impoverished south of the country. “You can imagine that environmental issues are not a priority on Peru’s urgent political agenda,” said Másquez.

Since the toma, Lake Imiría’s residents have been stuck in limbo. The Defense Front continues to limit the entry of NGO project staff while the communities determine the best course of action to recuperate their lands. Meanwhile, discord among the ranks in the other Shipibo communities, which Caimito residents say was sown by local NGOs and USAID, has broken down the more unified front that existed over the summer. “Many are still analyzing the situation,” said Samuel Sanchez Magin, a Junín Pablo resident.

Crossing the open waters of the lagoon on a small motorized canoe, ducks and ibis fly over the marshes. Herons perch on branches in the flooded broadleaf forests. At some point, the boat enters a labyrinth of wetlands with channels so narrow that it can barely pass; Jeremías Cruz Nunta uses a paddle at the bow to clear space.

Eventually, the shoreline of Unión Vecinal comes into view. Six people stand around a campfire boiling rice and cooking boquichico, a native fish. One couple and a man introduce themselves as farmers from Santa Rosa de Chauya; they traveled two hours from the connected lake the day before to take their shifts guarding the entrance from outside fishers and administrators who would seek to enter.

Santa Rosa de Chauya, like Union Vecinal, is one of the nine untitled hamlets in the area. Without any legal land rights, the residents exist in a highly tenuous position when it comes to making a living from the land they live on and gaining services from the state. Lake Imiría sits in a part of the Peruvian Amazon where Indigenous communities often find themselves in intense conflict with peasant farmers who, often with government support, migrate to their regions in search of affordable land. But the fight against the ACR has led to a collaboration and a strengthening of ties between the Shipibo communities that support the resistance and their mestizo neighbors, whose land use impacts pale in comparison to some of the larger threats in the region. “They’re some of the strongest supporters of the cause,” said Cruz Nunta.

Explore more from Grist’s series on The Human Cost of Conservation:

- How protecting the Earth became an excuse for murder

- In Sweden, a proposed iron mine threatens a World Heritage Site — and the culture that made it

- How the world’s favorite conservation model was built on colonial violence