This story was published in partnership with High Country News.

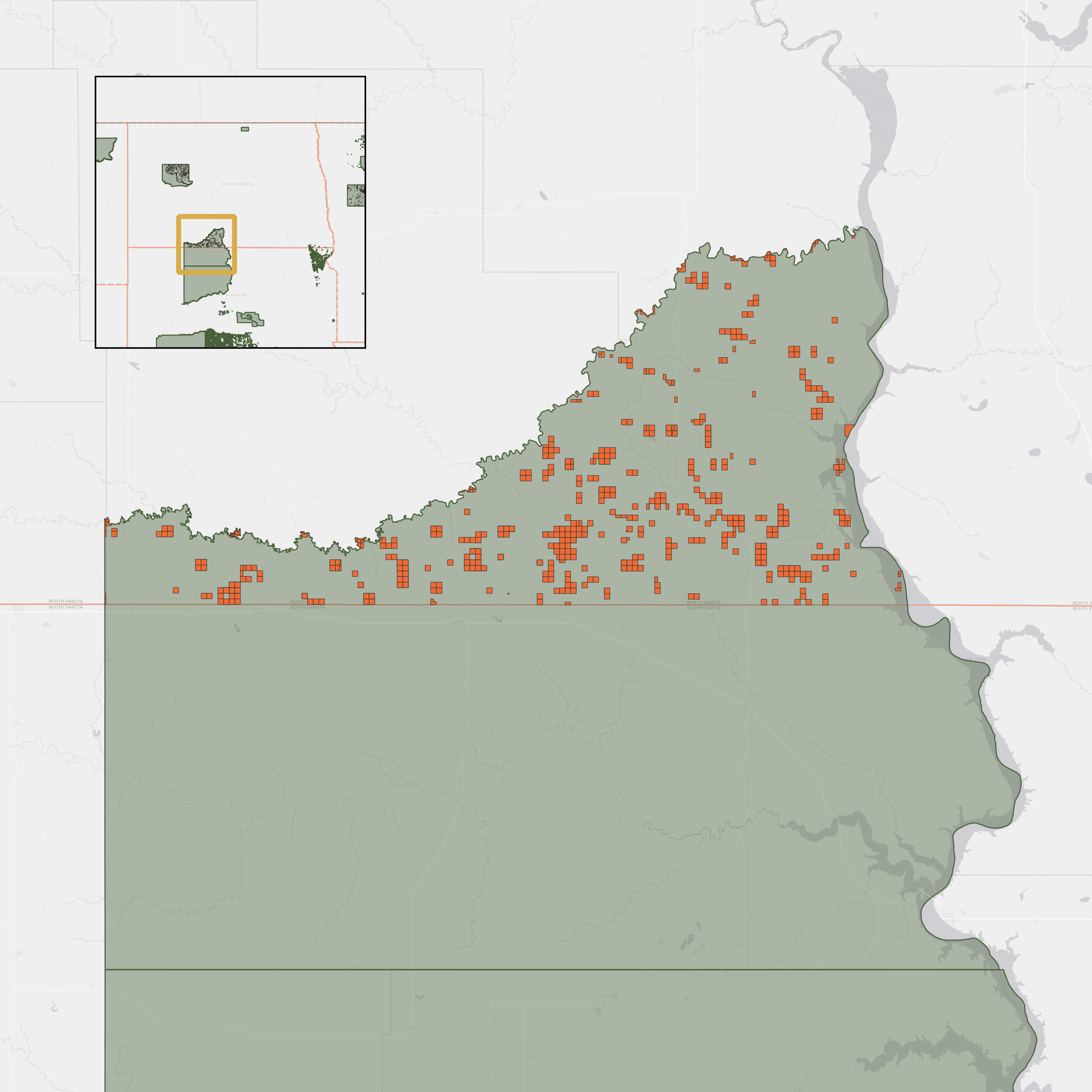

Before Jon Eagle Sr. began working for the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, he was an equine therapist for over 36 years, linking horses with and providing support to children, families, and communities both on his ranch and on the road. The work reinforced his familiarity with the land, and allowed him to explore the rolling hills, plains, and buttes of the sixth-largest reservation in the United States. But when he became Standing Rock’s tribal historic preservation officer, he learned that the land still held surprises, the biggest one being that much of that land didn’t belong to the tribe. Standing Rock straddles North and South Dakota, and both states own thousands of acres within the tribe’s reservation boundaries.

“They don’t talk to us at all about it,” Eagle said. “I wasn’t even aware that there were lands like that here.”

On the North Dakota side, nearly 23,500 acres of Standing Rock are managed by the state, along with another 70,000 of subsurface acres, a land classification that refers to underground resources, including oil and gas. The combined 93,500 acres, known as trust lands, are held and managed by the state and produce revenue for its public schools and the Bank of North Dakota. The amount of reservation land South Dakota controls is unknown; the state does not make public its trust land data and did not supply it after a public records request.

And Standing Rock isn’t alone.

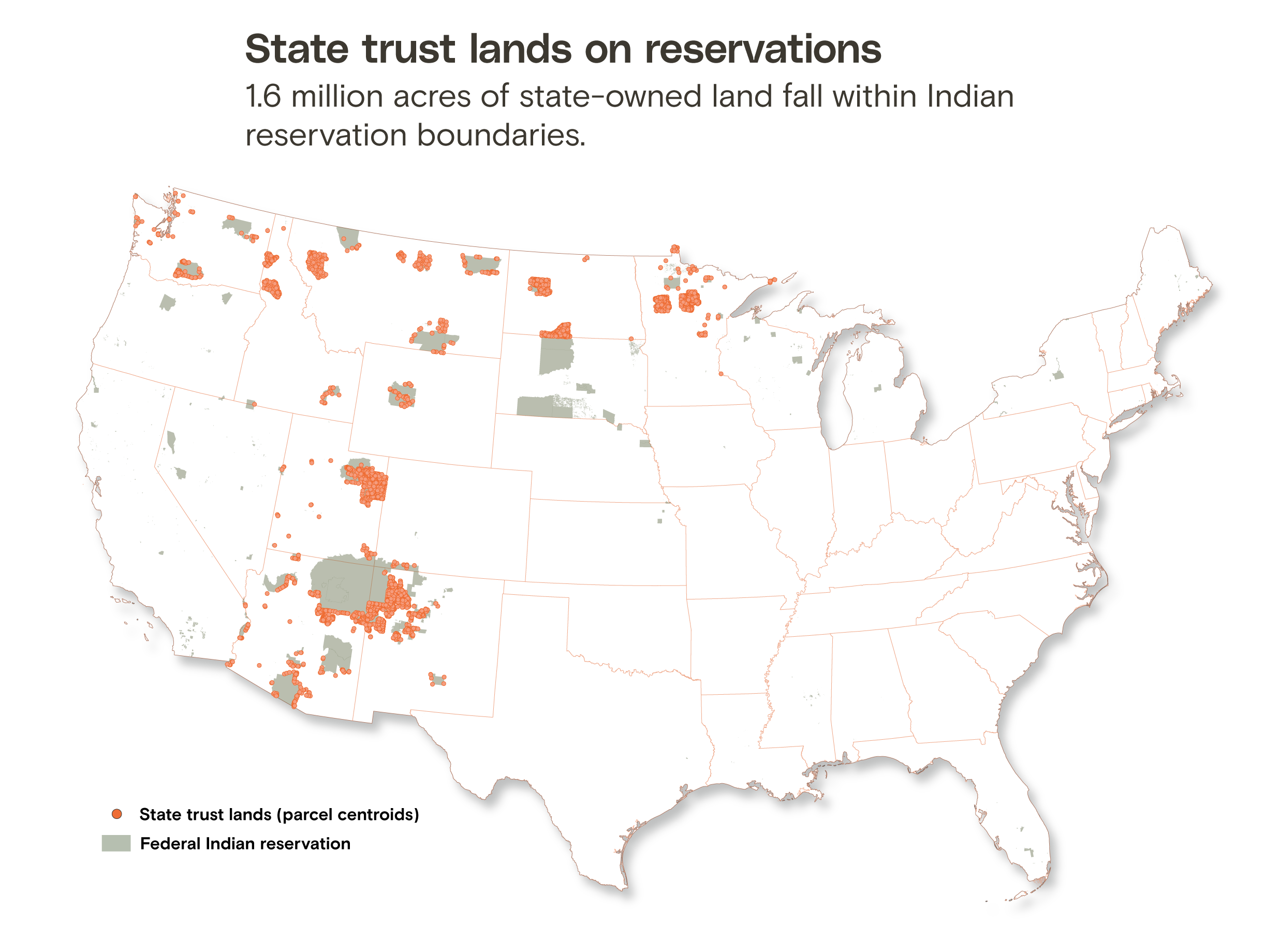

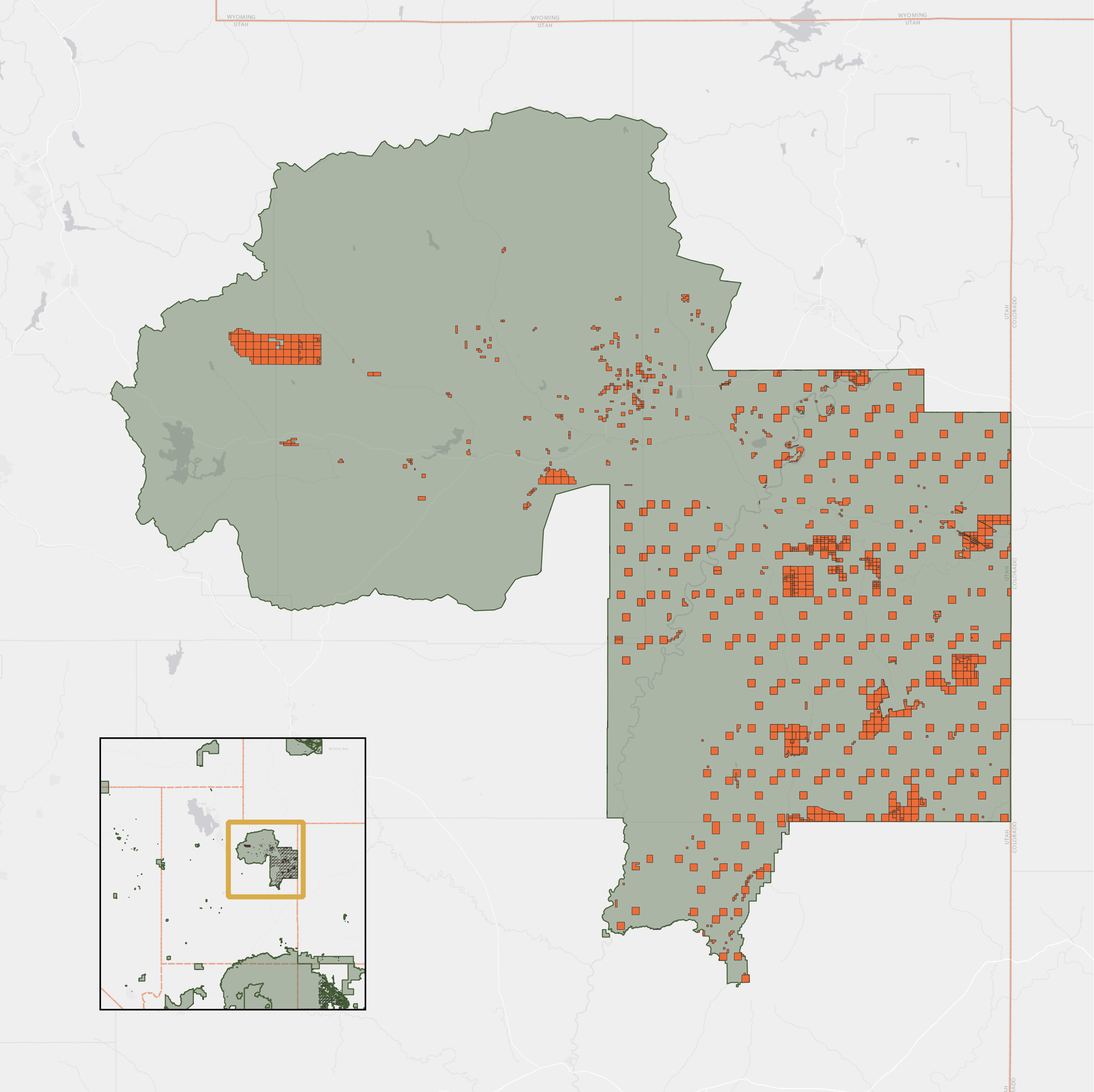

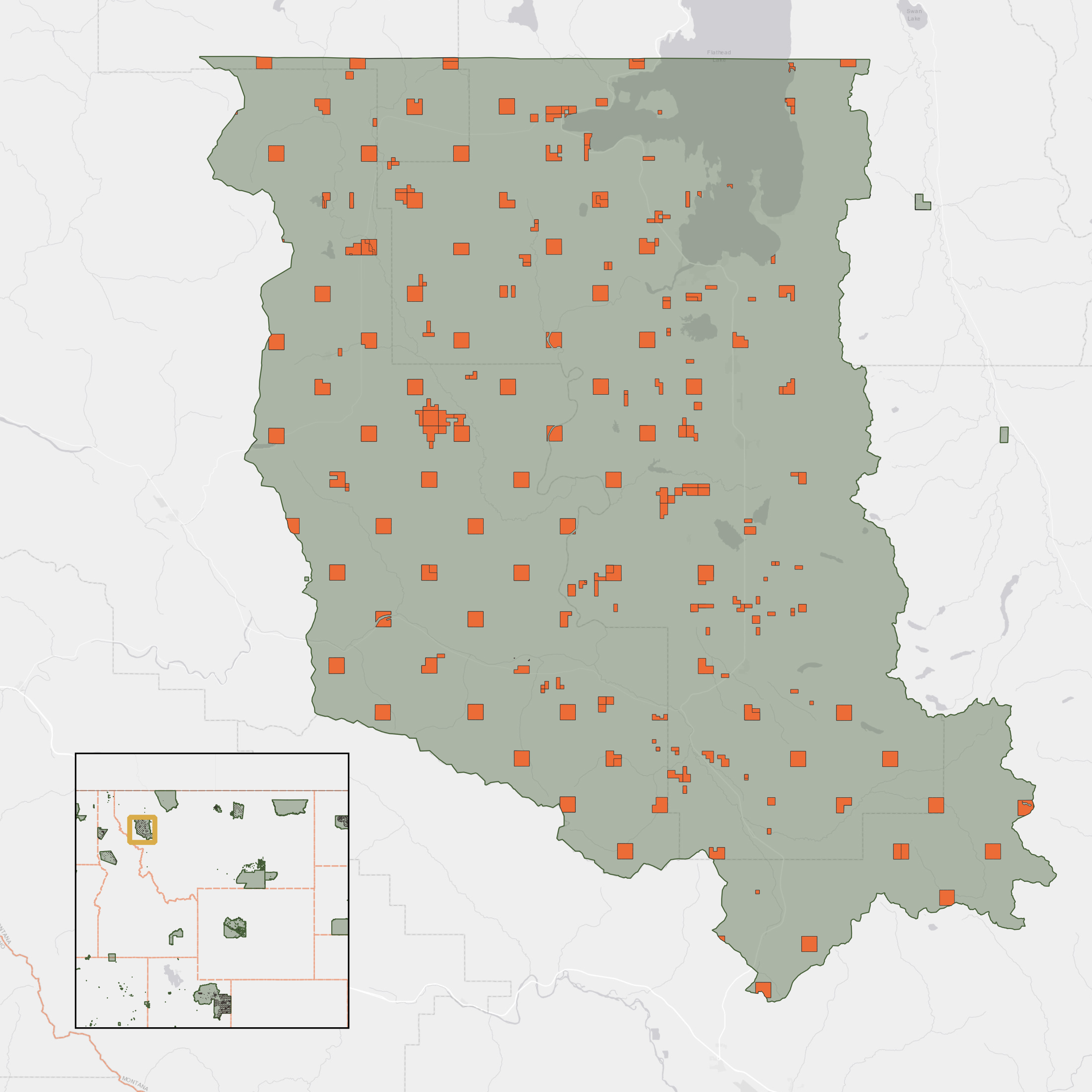

Data analyzed by Grist and High Country News reveals that a combined 1.6 million surface and subsurface acres of state trust lands lie within the borders of 83 federal Indian reservations in 10 states.

State trust lands, which are managed by state agencies, generate millions of dollars for public schools, universities, penitentiaries, hospitals, and other state institutions, typically through grazing, logging, mining, and oil and gas production. Although federal Indian reservations were established for the use and governance of Indigenous nations and their citizens, the existence of state trust lands reveals a truth: States rely on Indigenous land and resources to support non-Indigenous institutions and offset state taxpayer dollars for non-Indigenous people. Tribal nations have no control over this land, and many states do not consult with tribes about how it’s used.

Even in the obscure world of trust lands, states’ holdings within reservations have been almost completely unknown until now. Many of the experts Grist and High Country News reached out to, including longtime policymakers and leaders on Indigenous issues, were unfamiliar with state trust lands’ history and acreage. However, what sources did make clear is that the presence of state lands on reservations complicates issues of tribal jurisdiction in regards to land use and management and undercuts tribal sovereignty. According to Rob Williams, University of Arizona law professor and a citizen of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, this has broad implications for everything from the handling of missing and murdered Indigenous people to tribal nations’ ability to confront climate change.

“When there’s clarity about jurisdiction over Indian lands, it is easier for tribes to work with others to protect public safety, public health, and the natural environment,” said Bryan Newland, assistant secretary for Indian Affairs at the Department of Interior and a citizen of the Bay Mills Indian Community. “It’s been the longstanding policy of the department to reduce ‘checkerboard’ jurisdiction within reservations by consolidating tribal lands and strengthening the ability of tribes to exercise their sovereign authorities over their own lands.”

The creation of Indian reservations was followed closely by states entering the union, as well as successful attempts by state governments to carve up and dissolve those tribal lands.

Once states became part of the U.S., they received millions of acres of recently ceded tribal lands, many of which became trust lands. But as more settlers moved west, states pushed for more land. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the U.S. government responded by carving up Indian reservations, parceling out small amounts of land to individual tribal members, then handing over “surplus” lands for states, settlers, and federal projects. Known as the Allotment Era, the federal policy moved approximately 90 million acres of reservation lands nationwide from tribal hands to non-Native ownership.

According to Monte Mills, professor of law at the University of Washington and director of the Native American Law Center, allotment served a dual purpose: It broke up tribal power and gave non-Native citizens access to tribal lands and natural resources.

The allotment system, Mills explained, provided “a whole other set of opportunities for non-Indian settlers to get access to surplus lands and for the states to come in and get more state trust lands on lands that had been expressly off-limits.”

As Rob Williams put it, “The conquest was by law.”

“The implications of that policy are just devastating,” Williams said. “It’s hard to think of a single problem in Indian law that you can’t blame it in part on.”

For example, nearly 512,000 surface and subsurface acres on the Ute Tribe’s Uintah and Ouray Reservation came into Utah’s possession after a series of murky state and federal policies and land transfers. In 1898, just two years after Utah became a state, Congress began allotting land to individual tribal members without the tribe’s consent. A quarter of the tribe’s 4 million-acre reservation was taken by President Theodore Roosevelt for a national forest, while other land went to provide townsites and establish trust lands. By 1933, 91 percent of the Uintah and Ouray Reservation had been allotted.

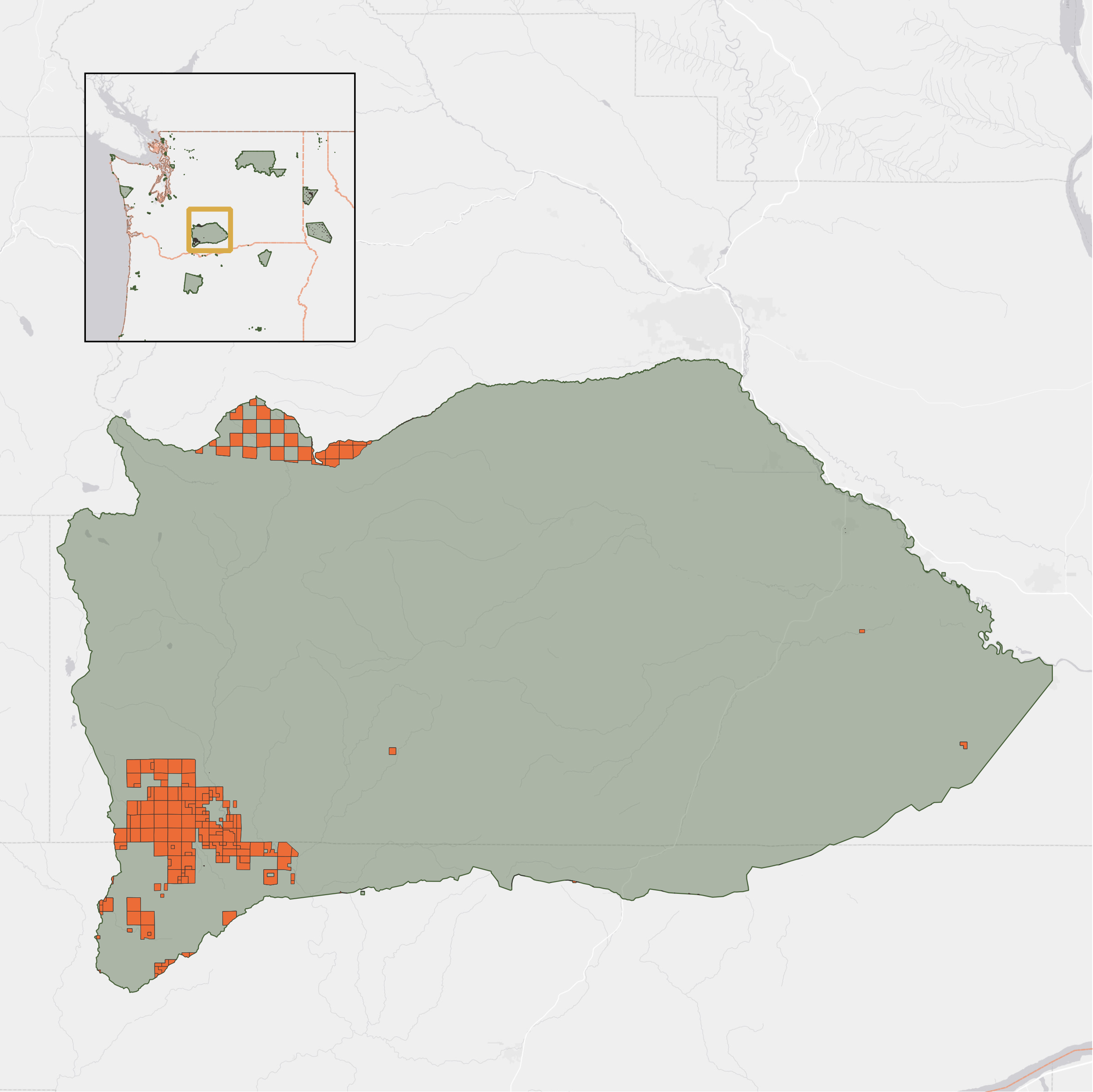

In other cases, as with the Yakama Nation, states acquired parcels when reservation boundaries were redrawn. Shortly after the tribe ceded over 12 million acres in central Washington, the agreed-upon map of its new reservation simply disappeared, sparking nearly a century of border disputes between the Yakama Nation, the state, and the federal government, specifically over a 121,000-acre section known as Tract D. In the 1930s, the map was rediscovered by an employee in the federal Office of Indian Affairs — apparently misfiled under “M” for Montana. In 2021, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the land was still a part of the original reservation. But in the meantime, Washington state had established trust lands inside Tract D. Today, 108,000 surface, subsurface, and timber acres inside the recently recognized borders of the Yakama Nation are still providing revenue for the state’s K-12 schools, scientific schools, and penal and reform institutions. This makes up 78 percent of all state trust lands on the Yakama Reservation.

Washington’s Department of Natural Resources, or DNR, is responsible for managing these lands. An agency spokesperson said, “The Yakama Treaty retained many rights for tribal members on public lands throughout the ceded territory of the Yakama, and DNR’s management of these trust lands continues to be done with much input from the Yakama Nation.”

Within the lines

In at least 10 states, trust lands are present within 83 tribal reservation boundaries.

Yakama

Yakama

Standing Rock

Standing Rock

Uintah and Ouray

Uintah and Ouray

Flathead

Flathead

Grist / Maria Parazo Rose / Clayton Aldern

Michael Dolson has spent most of his life on the western side of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes’ Flathead Reservation on his family’s ranch, started by his great-grandparents before allotment. Today, a map of the reservation shows large squares of state trust land parcels located not far from his family’s land: a total of 108,000 surface and subsurface acres that fund Montana’s K-12 schools and the University of Montana.

Dolson — now the tribe’s chairman — says that the state lands on the reservation are managed separately; the tribe has no input over how or whether Montana decides to log or lease them. Since different groups have different objectives, Dolson says, this complicates the tribe’s ability to manage its own reservation.

“I think we’ve gotten used to lands on the rez being owned by others, and they make use of those lands the way they want to,” Dolson said. “Do we appreciate that? Well, no. Especially when it’s parcels that have some sort of cultural significance to us, and we have no control over it, even though they’re on our own reservation.”

For more than a decade, the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes have carefully planned for climate change, documenting and developing tools, like drought-resiliency plans, to limit the impacts it could have. Meanwhile, Montana continues to prioritize oil and gas and coal production, making extraction one of the biggest sources of its trust land revenue.

Like many other tribes, the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes have had to buy back their own land, at or above market value. After allotment, less than a third of the reservation — about 30 percent — remained in tribal ownership. According to Dolson, about 60 percent of the Flathead Reservation, or 791,000 acres, is currently back in tribal ownership, following decades of strategic work. Yet Montana still controls 8 percent of the reservation as state trust land.

States are legally obliged to make money from state trust lands to benefit state institutions, so they are unlikely to return any land without getting something in exchange. But the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes may have created a model for how tribes can negotiate for large-scale transfers of land back to tribal ownership. In 2020, Congress passed a water-rights settlement that cleared the way for a transfer of nearly 30,000 acres of Montana state trust land back to the tribe. In exchange, the state will receive federal lands elsewhere; the acreage is currently in the process of being selected over the next five years. It’s a creative and unique arrangement, but one that presents opportunities — if states are willing to work with tribes.

Jon Eagle Sr. believes that systematic land theft has hampered tribes’ ability to manage the environment and protect their communities. The checkerboard parcels that allotment created are hard to manage; land-use policy is more effective over large, cohesive swaths of land. And returning land to tribal control gets complicated when state trust lands are involved: States don’t want to lose out on tax revenue.

The Biden administration’s policy is to assist tribes in reacquiring tribal homelands. But the policy is silent on the issue of state trust lands on reservations. There is currently no clear mechanism to return those lands to tribes. That means tribal nations have to work with states or else buy land outright — something the Ute Tribe tried unsuccessfully to do in 2019.

In 1969, Utah received 28,000 acres of land from the federal government inside the Ute’s reservation. Much of this land, known as Tabby Mountain, was converted to trust lands, and over the next 60 years it produced nearly $3.2 million in hunting and leasing revenue for state institutions, including Utah State University. In 2018, when the state put Tabby Mountain up for sale, the tribe was the highest bidder, offering nearly $47 million.

But shortly afterward, the state suspended the sale indefinitely, leaving the tribe unable to buy back its own land. Based on complaints filed by a whistleblower, the Utes allege that the state agencies responsible for the sale rigged the bidding process in order to prevent the tribe from reacquiring the land. The case is still in court.

According to Rob Williams at the University of Arizona, “The big issue now — and this is the burden on the tribes — is land back.”

Correction: A graphic in this story originally misidentified the number of reservations that contain land owned by states.