This post has been updated to include comment from Senator Booker’s presidential campaign.

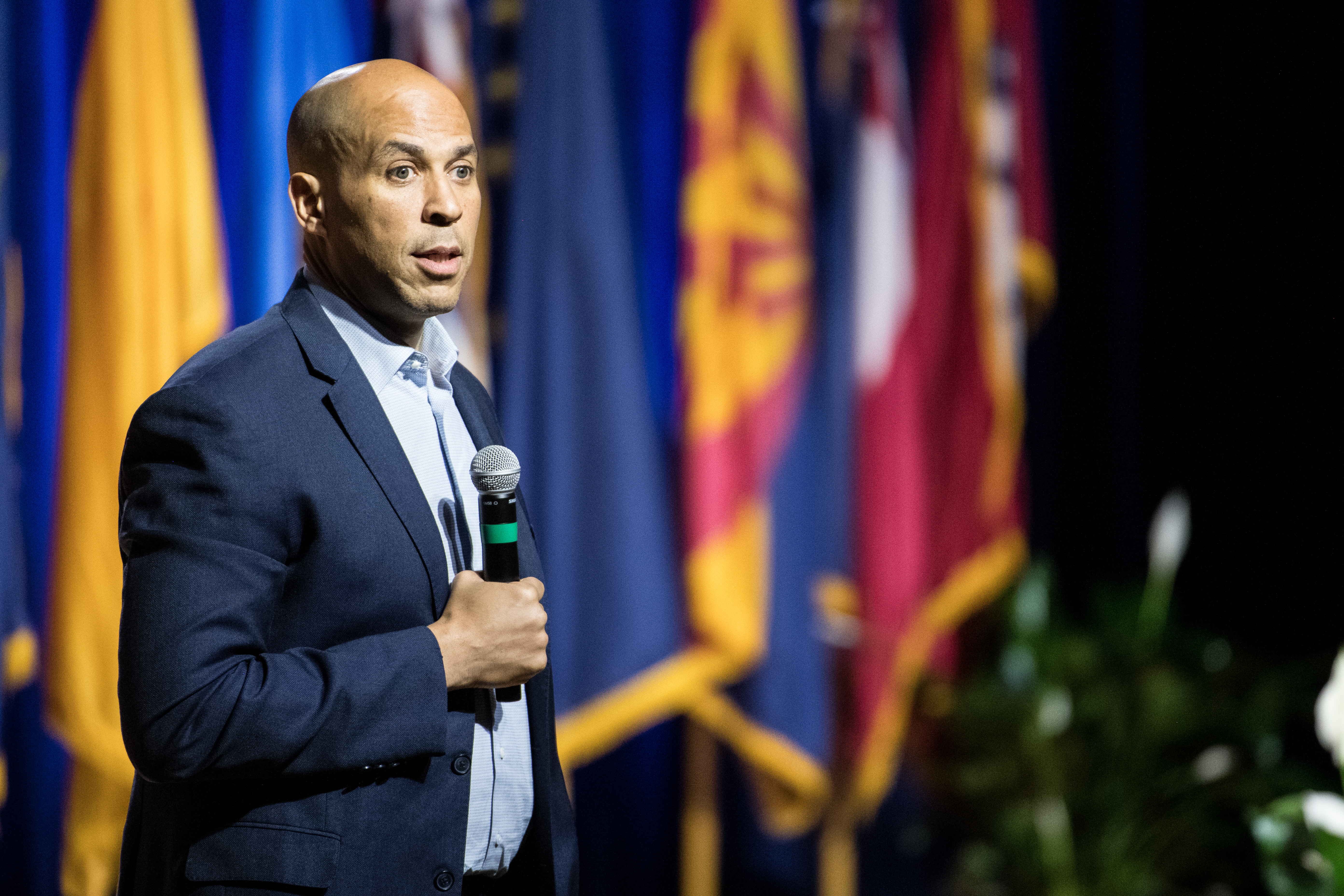

New Jersey Senator Cory Booker won’t be on the stage Thursday night at the sixth Democratic presidential debate in Los Angeles. While he hasn’t generated the poll numbers to join his fellow candidates, on the ground, some of his policy proposals are resonating with voters.

One, released earlier this month, stirred excitement among researchers, students, and grassroots leaders by promising to invest in historically black colleges and universities (or HBCUs). Booker’s plan is to invest $100 billion in HBCUs by upgrading their facilities, provide grants to expand their STEM education offerings, and expand climate change research at the schools. The proposal builds off Booker’s climate platform, which prioritizes environmental justice — healing communities suffering from polluting industries and protecting the Americans most at risk to the threats of extreme weather events.

“I am here today because of the power of these institutions to uplift and bring about opportunity to black Americans,” Booker said in a statement that accompanied the release of the proposal. Both of the senator’s parents were educated at HBCUs.

There are more than 100 historically black schools across the country, and many are struggling financially, as a result of underinvestment. Booker’s proposal notes that endowments at HBCUs are at least 70 percent smaller than endowments at non-HBCUs. According to the Thurgood Marshall College Fund, which represents the community of black colleges, the institutions also disproportionately enroll low-income, first-generation, and academically underprepared college students. Today, the Fund reports, nine percent of all African-American college students attend an HBCU, and more than one in five earn their bachelor’s degree from these schools.

For Beverly L. Wright, a sociologist who founded and oversees the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice, Booker’s ideas, if enacted, would tap the communities most likely to be exposed to environmental pollution and experience the effects of warming to solve both issues. “One of the major reasons that environmental justice communities have been overlooked in the search for solutions to climate change is because the faces and the interests of the people heading up the research does not include us,” Wright said. “I really believe that HBCUs are in the best position to focus the research in such a way that there’s equity in the decisions that are made.”

The senator’s campaign said Booker created his climate plan to reflect the historical challenges these communities have endured, such as policy decisions that have led to pollution and contamination in their neighborhoods. “It’s not just about the climate challenge that’s ahead of us, it’s also about remedying the systemic cost and the systemic racism that has led to the cost for communities of color,” said a policy advisor with the campaign. “How do we make them part of the solution and make sure that investments in this are not just going to research centers on the coast?”

Booker’s plan aims to empower these communities by creating more researchers and leaders in technology fields who hail from them. This, in turn, will help in developing solutions to problems, such as contaminated lead water mitigation or superfund clean-ups, with the buy-in of decision makers who are rooted in those areas, noted the policy advisor. The senator also wants to require that at least 10 percent of his proposed climate-moonshot hubs — research centers that will tackle everything from curbing greenhouse gas emission sources to optimizing renewable energy sources — be based at HBCUs, as well as other minority-serving institutions.

Such a funding surge to HBCUs would, among other effects, boost the research these campuses are already doing in vulnerable communities from Texas to Alabama, and could take some of these colleges, which are operating on financial tightropes, from surviving to thriving, say academic experts. Marybeth Gasman, an education professor at Rutgers University, told the New York Times that, if Booker could pull off such an investment, “it would be historic.”

Amanda Masino, associate professor of biology and chair of natural sciences at Huston-Tillotson University, a historically black university in Austin, Texas, said the resources would allow HBCUs not only to expand the reach of their research beyond the immediate vicinity of the schools, but also to take on bigger projects. “We have students and faculty and staff who have for decades been making gold out of straw, and that’s exactly what we can and will and have done in climate work,” she said.

HBCUs and their students are often deeply connected to surrounding communities of color, and Booker’s plan could strengthen that bond, Masino explained. “That’s the piece of it that’s important: Treating the HBCUs as the incredible resource they are,” she said. “This is the place where you have the combination of rootedness in community, appreciation of social justice and history of social justice, and just some really smart, creative, motivated people who, if you give them the resources, are going to get the job done.”

Over the last two years in East Austin, where Huston-Tillotson is based, Masino and a group of undergraduate students have been studying air quality and housing affordability in the surrounding neighborhoods — historically impoverished African-American enclaves that are undergoing gentrification, but are still stratified by race and income. While gathering air-quality readings, her students conduct surveys that are supposed to take 10 minutes — but they often linger for up to an hour because residents are eager to share their experiences.

“They recognized us and recognized the school and they recognized that the sorts of things we were asking about are the issues they care about too,” Masino told Grist. “And they knew that we were on their side, that we were collecting information because we knew that their voices weren’t being heard.”

As part of a broader green campus transformation, Huston-Tillotson began offering an environmental justice major last year, which Masino directs. The school has also increased outreach in the community through projects such as the Historically Black College and University Climate Change Consortium, which was created by Beverly Wright and environmental justice scholar, Robert D. Bullard, in order to raise awareness about the disproportionate impact climate change has on marginalized communities.

At its annual conference, the consortium brings together students, teachers, environmental experts, and community members. Exposing young students early on to the role they can play in solving climate justice issues is key, Wright told Grist. But that requires funding curriculum and research at all levels of the educational system, she said. Wright sees HBCUs as an ideal place to invest because these institutions educate a large portion of students from climate-vulnerable areas.

Booker states in his proposal that he’s hoping to create new avenues for those from communities that have been “deprived of wealth, opportunity, and their voices as citizens.” People who grew up like Frederick D. Randall II, an environmental law student at Vermont Law School.

Randall, who earned his bachelor’s degree from the historically black Alabama A&M University, plans to focus his career on energy policy and environmental justice. But his path to law school was forged in large part by his desire to address the injustices, including environmental ones, faced by his family and other African Americans. Throughout his home state of Alabama, it’s communities of color who are most likely to suffer the harm of living near factories, breathing polluted air, and drinking contaminated water, said Randall, who is from the state capital of Montgomery. The various types of racism his relatives have experienced inspired him to seek solutions to address the poverty and economic inequities still faced by those who live in these area.

While Booker’s plan is only part of a presidential platform at the moment, Randall said the proposal “would certainly help push the needle toward remedying some of the wrongs occurring in black and brown communities.”