Anna Sanchez felt a surge of pride as she watched her 9-year-old son, Nathan, pull on the boxy, gray and white costume. The outfit had been made by a fellow demonstrator rallying against the stifling air pollution in San Bernardino County, California, where Sanchez and her son live. None of the protesters could comfortably fit inside the cardboard sheath made to look like a warehouse. So Nathan stepped up.

“Let’s do this,” he said happily, his head bobbing about a foot below the 20 or so adults surrounding him. They were gathered in front of the house of a San Bernardino County supervisor. The official had recently voted to rezone a residential area in a largely rural part of the community to allow for the construction of a new distribution center.

Nathan raised a bullhorn to his mouth and began to chant: “Kids’ health before wealth!” Sanchez smiled. It was the first time Nathan had joined her at an environmental protest.

“Right now he doesn’t really understand how he was directly impacted by it,” Sanchez said of the Southern California county’s air quality — the worst in the nation for ozone pollution, according to the American Lung Association’s most recent State of the Air report. “But he does understand that it’s an issue, and he understands that kids are being hurt.”

Nathan Sanchez (foreground) cheers on his fellow protesters as they rally outside the home of San Bernardino County Supervisor Josie Gonzales last October. Photo courtesy of Anna Sanchez

Only an hour-or-so drive from Southern California’s beaches but a world away from the glamour of Hollywood, San Bernardino County is one of the country’s biggest hubs for warehousing and distribution of goods. For many SoCal city-folk, the area encompassing San Bernardino and neighboring Riverside counties, known as the Inland Empire, has long been thought of as an “alien place,” at best a pit stop at the edge of the desert on the long drive to Las Vegas. Joan Didion, the great chronicler of California, once called the region “a harsher California, haunted by the Mojave just beyond the mountains.” But for those who make their homes here, the I.E. has been a haven to escape the bigger cities and skyrocketing housing prices closer to the coast.

There’s a long history of families seeking refuge in San Bernardino County. “Okies” fled to the area during the Dust Bowl in the 1930s, traveling by way of Route 66. In recent decades, black homeowners have left more crowded and expensive Los Angeles County for the I.E. People have also flocked there from Latin America and Asia — 1 in 5 area residents is an immigrant.

But the abundance of cheap land has been an even bigger lure to the logistics industry — the businesses associated with the storage and movement of goods for retail and e-commerce. Every year, tens of billions of dollars of imported goods enter the United States and pass through the Inland Empire, either by train, truck, or plane. Becoming a crucial hub of international trade has been an economic boon to the area, but there have been consequences, mostly from pollution associated with the movement of goods.

“There’s no question that truck traffic and air quality is an issue,” said John Husing, an economist and local icon who works with the Inland Empire Economic Partnership, a group of local governments and industry bigwigs. But the region’s poverty, he contends, is the bigger hazard to its residents. “How do you weigh the various ways of looking at public health?” he asked.

The Inland Empire’s economic appeal stems from its geography — but so do its air quality issues. Fewer than 100 miles west, the San Pedro Bay Port Complex, which is made up of the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, is the busiest in the United States and the ninth busiest in the world. Last year, it broke a record for the highest volume of shipping containers ever moved by a seaport in the entire Western Hemisphere. A significant portion of those goods doesn’t stay on the California coast long before being loaded up and sent east to be sorted and shipped from a growing network of warehouses within the Inland Empire.

“Why is this all in the Inland Empire? The answer is, there’s nowhere else to put it,” Husing said. If you run a major online retailer, he continued, “You have to be here.”

An aerial view of San Bernardino International Airport which has attracted some major businesses, like Kohl’s, Pepboys Auto, Mattel and Stater Bros. to establish warehouses. Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times / Getty Images

East of the Inland Empire are the San Bernardino Mountains. To the north are the San Gabriels. The region sits in a valley between the two forming a bowl that traps air heavy with car emissions drifting inland on the coastal breeze from nearby Los Angeles.

San Bernardino County not only has the country’s worst ozone pollution — better known as smog — it consistently ranks among the worst counties for year-round particulate pollution, or soot. (That’s even considering that it’s the largest county in the U.S. and includes postcard-worthy places such as Big Bear, Lake Arrowhead, the Mojave National Preserve, and parts of Joshua Tree.) Its toxic brew is made worse by rapidly proliferating warehouses, as well as one of the busiest railyards in the country — which is located on the West Side of the city of San Bernardino, where airborne particles from diesel emissions are at some of the highest levels in the U.S. The distribution centers and the rail hub draw thousands of trucks each day. San Bernardino County has accumulated nearly 300 million square feet of warehouse space — enough to fill more than 5,100 football fields. Kohl’s, Mattel, Skechers, and Pepsi are among the brands that have set up shop. Amazon’s fulfillment and sorting center — the first of its kind in the state — is now the region’s largest employer. Walmart has plans to build a 340,000-square-foot consolidation center there later this year.

Husing pins this explosion of activity over the past two decades on Americans’ insatiable appetite for stuff. “What’s driving this is the public,” he told Grist. “We want relatively inexpensive goods, therefore, we want the Walmarts. And then we also want e-commerce in a hurry.”

There’s no arguing that the warehouses have brought jobs to an area that needed them badly. As the country came out of the Great Recession and business infrastructure expanded, the county’s unemployment rate has steadily dropped, falling from a high of 14.2 percent in 2010 to a recent 4.3 percent.

The logistics industry is now an integral part of the San Bernardino County community. But the economic activity associated with our national shopping habit comes at a cost for families, like Sanchez’s, who live here.

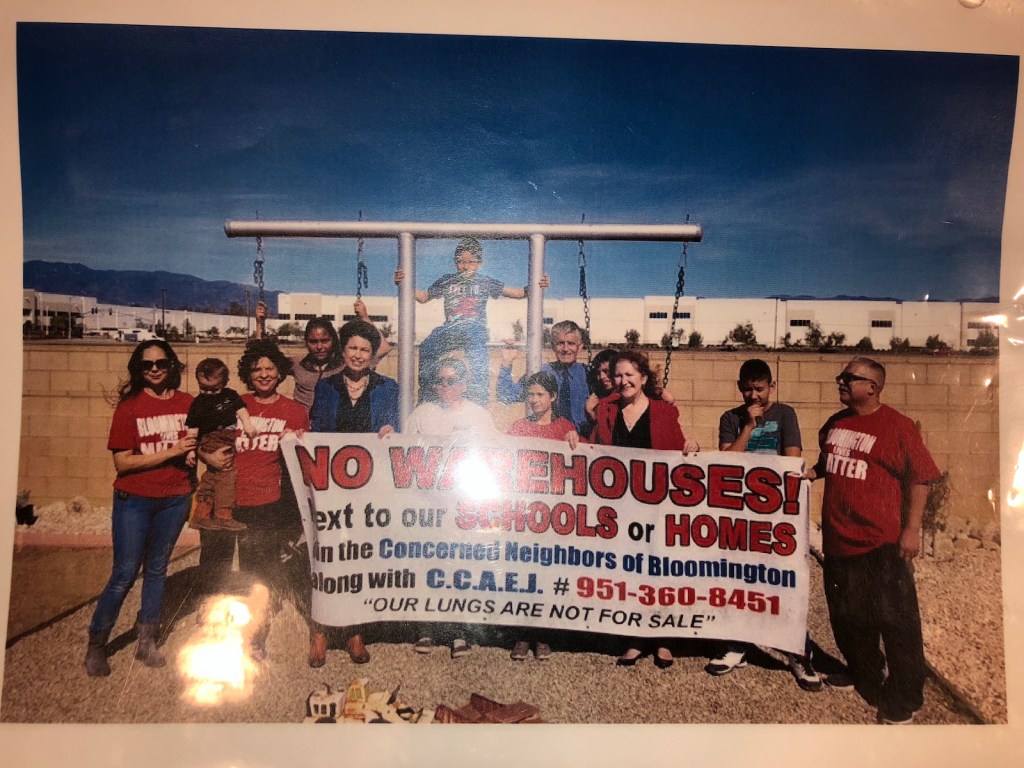

Even before the warehouses started popping up, environmental activists in the Inland Empire, mostly women and mothers, were pushing back against industry for the health of their kids and their neighbors — taking on waste dumps, the railyards, and the county public transit authority. Today, they say that the balance between economic gain and public health is even more out of whack. Some community members have argued that many of the new logistics jobs lack good benefits and don’t pay enough to support a family. Much of the work is seasonal or vulnerable to being replaced by automation. Further, the encroachment of warehouses on residential areas could be putting workers and their families at risk.

San Bernardino County residents suffer from a range of maladies, including higher than state average rates of infant mortality, low-birth-weight babies, and various forms of cancer. As more of them become sick and a growing number of studies link worsening air quality and the health conditions seen in the region, women like Sanchez are organizing to stop the encroachment of the logistics industry on the places their families live, work, and play.

In communities all over the country, women are driving grassroots efforts to protect local environments — from shifting the local economy away from coal in Appalachia to stopping an oil-by-rail export terminal from being built in Washington State. And that’s also the case in San Bernardino County.

“Mothers go to doctors appointments with their children; mothers are very involved in the community because they have to be,” Sanchez said. “So when they see things, it’s like, ‘Oh no, something needs to be done.’”

“We’ll continue to see mothers going out there and standing up for their children,” she added. “Women understand.”

[jumbo-content]

[/jumbo-content]

Some health problems come down to chance. Two people could live their lives in the exact same way under the exact same conditions, and one could develop a disease while the other remains healthy. But when many people come down with the same illness while living in the same place, residents — and then scientists — start to ask: Could the cause be something in the community?

In certain areas of San Bernardino County where diesel fumes and ozone pollution are especially high, there are an awful lot of health problems to ask about.

Teresa Flores Lopez lives in one of those neighborhoods, the West Side community in the city of San Bernardino. Unlike in other cities where zoning rules divide residential areas and industrial parks, many San Bernardino homeowners have properties adjacent to high-traffic hubs for goods. Across the street from the main entrance to one of the country’s busiest railyards sit a soccer field, a community center, and what remains of Flores Lopez’s grandparents’ home, where she spent much of her childhood. Over the span of five minutes on a recent Thursday afternoon, more than two dozen big rigs streamed in and out of the railyard.

The West Side is a largely working class, Latino community. A recent analysis by the Union of Concerned Scientists found that Latinos in California, compared to white residents, are exposed to particulate matter pollution that is almost 40 percent higher on average. Even in the county with the highest ozone levels in the country, the West Side has particularly bad air. Flores Lopez’ neighborhood has twice the pollution burden — the potential exposure to pollution and its related adverse environmental conditions — compared to the rest of the state.

Flores Lopez recently took me to the spot where her grandparents’ house stood. The home, once painted mint green, is gone now except for the mailbox. Standing on a plot of dirt where stairs once lead to the front door, she looked inside for mail. There was none.

Teresa Flores Lopez checks the mailbox that marks the site where her grandparents’ home stood. She said the house, in the city of San Bernardino’s West Side neighborhood, was torn down to make way for the expansion of the nearby BNSF rail yard. Justine Calma / Grist

Sections of the block, including what was once her home, have been demolished to make way for the railyard to expand, Flores Lopez said. When she was a kid spending Sunday afternoons at her grandparents’ home after church, Flores Lopez said the bustling train depot was already larger than life.

“The house would rattle,” she recalled, as they heard the banging of train cars. Flores Lopez’s grandfather worked as a foreman for the railroad back when it was owned by the Santa Fe Railway. In the mid-90s, big rigs started showing up after the railyard became “intermodal” — receiving and distributing imported goods from nearby ports via train and truck at all hours. The hub is now owned by Warren Buffett’s BNSF Railway Company, one of the largest freight railroad networks in North America.

As the 63-year-old mother of three walked across the abandoned lot, she moved slowly and deliberately, a result of a stroke that left her partially paralyzed on her left side. “If a cop pulls me over and asks me to walk in a straight line, I’m going to be in trouble!” Flores Lopez joked.

She was in her early 50s and living with her husband in the West Side house when she suffered the stroke. Flores Lopez largely attributes the event to the stress she was under from having to care for her father and sister, both of whom were ill at the time. But she said she was also “being accosted from all the stuff that was happening across the street.” Several studies have connected exposure to air pollution with increased risk of having a stroke. The risk is particularly high for older women like Flores Lopez who live close to sources of diesel soot, car exhaust, and other airborne toxins.

A third source of stress came from her work organizing against pollution from local industry. It all started one afternoon shortly after the nearby elementary school finished its classes for the day. Flores Lopez had a habit of standing at her front gate to make sure the kids coming out of school crossed the street safely. That’s when her neighbor Marilyn Alcantar came over to ask if she could smell gas. Alcantar lived in a home behind Flores Lopez’s with her husband and four children. Alcantar suspected that the stench was coming from a facility across the street from the elementary school, where she worked as a teacher’s assistant. The site stored more than 100 public buses owned by Omnitrans, the county transit agency, and the natural gas tanks used to fuel them.

Alcantar and Flores Lopez started talking with other women — many of them stay-at-home moms who spent all day breathing the neighborhood’s polluted air. Through those conversations, they began to wonder if all the activity around them — the buses, the trains, the trucks — could also damage the health of their neighbors and their children. Together, they formed a grassroots group they called the West Side Residents for Clean Air Now.

Flores Lopez had read an article about Penny Newman, the founder of an organization in neighboring Riverside County called the Center for Community Action and Environmental Justice. Newman and another group of mothers started the group in the late 1970s to protect their families from pollution coming from the Stringfellow Acid Pits, about 15 miles from San Bernardino. The group’s work established the industrial waste dump as one of the Environmental Protection Agency’s first Superfund sites.

Flores Lopez and Alcantar’s West Side group eventually joined forces with Newman’s in a campaign to relocate Omnitrans’ natural gas tanks. It took 20 years of knocking on neighbors’ doors, speaking out at hearings, and meeting with city officials to win a victory against the agency. Ultimately the alliance was successful in getting Omnitrans to install a new fueling system that connected directly to the city’s natural gas pipeline. According to an Omnitrans spokesperson, community concern was one of the main drivers behind the change — though the switch also saved money. (Omnitrans maintains the storage tanks posed little health risk.)

Along the way, Flores Lopez and her neighbors also took action on the diesel trucks that suddenly swarmed through their neighborhood. She says she asked city officials to put up signs warning trucks not to park in front of residences. And they successfully pushed the city to close off an entrance from her street to the nearby Mt. Vernon Bridge, forcing trucks to find another route.

San Bernardino’s West 4th Street separates a residential neighborhood from an industrial zone. To the north, is a park, daycare center, and dozens of homes. To the south: one of the nation’s busiest rail yards, which hosts truck and train traffic 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Justine Calma / Grist

As she and her group racked up community-wide victories, they suffered personal losses. Flores Lopez and Alcantar both lost sisters to kidney failure and cancer, respectively. Not long after Alcantar started organizing with Flores Lopez, she was diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which is commonly linked to ozone pollution. Alcantar had never smoked. She lived with the disease for 15 years, as she continued fighting Omnitrans. It was a reminder of the air’s potential impact on her own health. In a 2011 report, Alcantar told organizers at CCAEJ that she fully expected to have cancer by the time she was 70.

Then, in 2017, with nearly a decade left before she turned 70, her prophecy came true. Doctors found malignant tumors between Alcantar’s pancreas and gallbladder.

Alcantar’s husband, Bobby, explained that his wife’s love of the neighborhood’s kids fueled her concern for the local environment. “It started with the kids at school, making sure that they were all healthy,” he said.

Teresa Flores Lopez (center, standing) and Marilyn Alcantar (sitting, center) pose with members of the local public transit authority after the agency agreed to remove natural gas storage tanks from a facility in their neighborhood. Flores Lopez told reporter Justine Calma about how she and Alcantar met. Photo courtesy of Teresa Flores Lopez

Alcantar was present at the unveiling of Omnitrans’ new compressed natural gas system. Flores Lopez had cajoled her into attending the ceremony days after Thanksgiving 2017, even though her friend had to come in a wheelchair. When the two women saw the empty space where the storage tanks used to be — it looked like a tomb, Flores Lopez said — both cried. They were tears of anger, Flores Lopez recalled, not joy: “Why did it take this long for them to do this?”

Less than a month after the ceremony, Alcantar died. Of the original group of women who initiated the campaign against Omnitrans, Flores Lopez is the only surviving member. The others eventually succumbed to various forms of cancer, like Alcantar, or kidney failure.

“Every time I’ve had an illness, I’ve sat there and said prayers,” Flores Lopez said. In each case, she told God: “If you’re ready for me, I’m ready.”

Until He is, she’ll continue to fight.

[jumbo-content]

Justine Calma/Grist

[/jumbo-content]

The struggle for San Bernardino’s air is entering its third decade, and a new generation is taking up the mantle. Anna Sanchez was only a kid when Flores Lopez started organizing women in the West Side. Now 27, she has her own child in mind when she’s fighting for the community’s health.

A decade ago, when Sanchez was pregnant with her son Nathan, she was living in a house near both the railyards in San Bernardino’s West Side and the former Norton Air Force Base Superfund site. A few months before Nathan’s birth, Sanchez found out he had gastroschisis, a serious birth defect in which the fetus’s intestines develop outside of the abdomen.

During her high-risk pregnancy, researchers at nearby Loma Linda University recruited Sanchez to join a study looking at mothers in the Inland Empire area whose children were all born with the same condition. Examining 257 cases of gastroschisis treated at Loma Linda University Medical Center between 1998 and 2012, researchers determined that cases of the birth defect tended to occur around major transportation routes. They said more research was needed to specifically look at the relationship between the clusters and environmental toxins from nearby Superfund sites and polluting industries.

“I was shocked,” Sanchez said. “I wondered, ‘How many more women are going through this?’”

She posted the study’s findings on Facebook. Shortly afterward, Sanchez said, a friend who lived nearby reached out to let her know she had also become pregnant with a fetus with gastroschisis. The friend wasn’t accounted for in the Loma Linda study because she miscarried.

Anna Sanchez’s son, Nathan, was born with gastroschisis — a condition in which the intestines develop outside the body. Researchers at Loma Linda University found that the birth defect could be linked to mothers living near major transit centers. Photo courtesy of Anna Sanchez

Pregnant women and babies are especially vulnerable to poor air quality in San Bernardino County. The county ranks in the top 10 in the state for percentage of infants born with low birth weight, a major risk factor for infant mortality. The West Side, bordering the railyards, has the highest infant mortality rate in the county, according to latest estimates: The leading causes of death in the county are birth defects, pregnancy complications affecting newborns, sudden infant death syndrome, and prematurity/low birth-weight — all of which have been linked to poor air quality.

A spokesperson for the San Bernardino County Health Department told Grist that the agency does not have the capacity to conduct research into whether air pollution is a contributing factor to the high rates of infant mortality and low birthweight in the county. But other institutions have taken up the research.

Beate Ritz, an epidemiologist at the University of California at Los Angeles, studied air pollution’s influence on infant death in Southern California from 1989 to 2000. She found that infants between the ages of 7 months and 12 months who had been recently exposed to high levels of particulate pollution had double the risk of death from respiratory problems. Babies exposed to nitrogen dioxide — one of the pollutants found in diesel emissions that leads to the creation of smog — showed an increased risk of SIDS.

“Every health effect is probably caused by a multitude of different things,” Ritz said. “And then your question is, well, what’s the last drop in the bucket that brings the bucket to overflow? And air pollution contributes.”

Sanchez has a daily reminder of the damage that air pollution can cause. Before Nathan was born, she had dreamed of being a nurse. Instead, she is attending Pepperdine University in Malibu to become an environmental lawyer. Her goal: protecting people in her hometown from polluters.

“I didn’t want other people to go through this,” Sanchez said. “This is a continuing thing: more pollution, more birth defects.”

San Bernardino County residents have had a complex relationship with industry for decades. As Teresa Flores Lopez worked to clean up the air surrounding the railyards, her husband Nick went to work at the railway company, his employer for nearly 40 years. Flores Lopez said it’s not a contradiction; it’s just the way things are around here. The railroad, Flores Lopez said of her family, “is in our blood.” Many of the environmental advocates Grist spoke to in San Bernardino County have ties to some aspect of the industry.

“We lived comfortably because of the railroad,” Nick told Grist. Still, he remembers regularly cleaning a thick layer of black dust that gathered inside their home across from the railyard. Sometimes, he’d develop unexplained nosebleeds. After he retired four years ago, the couple sold their house next to the railyard and moved a few blocks away. The dust cleared. The nosebleeds stopped.

“The greater San Bernardino region was built around transportation centers like Santa Fe Railroad and Norton Air Force Base,” said San Bernardino Mayor John Valdivia, who took office in December. “Logistics has played an important role in supporting economic growth.”

Shipping containers are transferred from trucks to trains at the BNSF rail yard in West San Bernardino. The county has the worst ozone pollution in the country, and diesel emissions are particularly high in the neighborhood surrounding the railyards. Justine Calma / Grist

Valdivia campaigned on a platform promising to cut “the costly bureaucratic red tape that prevents job growth” and “create a one-stop permitting shop to expedite business growth and encourage employers to locate here.” But Flores Lopez, Sanchez, and other residents say the promise of new logistics jobs is no longer enough to compensate for the hazards they associate with the industry.

Many of the new warehouse and railyard jobs are temporary positions. They’re in great supply as the holiday shopping season picks up and dwindle as it passes. Locals say the seasonal jobs offer nothing like the security and benefits that used to come with a job at the railyard. Workers complain about warehouse conditions — telling Veronica Alvarado, a program director at the Warehouse Worker Resource Center in the Inland Empire, that they get dizzy when opening containers and nosebleeds from trucks idling outside the buildings.

“It’s pretty gross and disgusting that we can be sold the idea of ‘Shut up, just take these jobs!’” Alvarado said. “We want good jobs, where health and safety are respected.”

Concerns about the booming logistics industry have recently led to some unlikely partnerships pushing against business as usual in the Inland Empire. In the past year, labor, immigrant, faith-based, and environmental advocates — all worried about rising risks to health and safety — have formed a coalition to protect communities surrounding the San Bernardino International Airport, where a massive new air cargo logistics center is slated to be built on the footprint of the former Air Force base. The center is expected to bring 3,800 new jobs and $5 million in revenue for the city.

The Inland Valley Development Agency, which is responsible for redeveloping the base for public and commercial use, says that the air cargo logistics center will also include a 3.75-megawatt solar system and result in local infrastructure and road improvements. Mike Burrows, executive director of both the Inland Valley Development Agency Board and the San Bernardino International Airport Authority Commission, told Grist that the facility’s sustainability features will make it “a model for other projects in the Inland Empire.”

But that’s not necessarily enough for the activists, who are pushing for an agreement that would hold developers accountable for hiring locally, providing stable jobs, and keeping their pollution in check. It’s a conversation Burrows said he’s open to having.

Growing online shopping demand continues to drive the construction of more fulfillment centers in the region. The centers are being built to aid the demand for 24-hour delivery, economist Husing explained. He forecasted long-term growth in this area. Between 2009 and 2019, e-commerce sales as a percentage of total quarterly retail sales in the U.S. more than doubled from roughly 4 to 10 percent.

On May 1, members of the newly formed coalition hoping to hold developers like Burrows accountable gathered for a demonstration commemorating May Day, a day traditionally set aside by activists to take to the streets in support of workers’ rights. Ericka Flores, the organizing director for the Center for Community Action and Environmental Justice, led nearly 300 people in a march past San Bernardino’s courthouses, county buildings, and city hall. It was a colorful crowd — purple shirts for the home care workers union, orange vests for the warehouse workers resource center, red for the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights.

“We haven’t been as strong working alone,” explained Celene Perez, political director of the Inland Empire Labor Council, which represents more than 200,000 union members throughout San Bernardino and Riverside counties.

Ericka Flores (top right) rallies environmental, labor, and immigrant rights advocates as they march past San Bernardino City Hall on International Workers’ Day. Justine Calma / Grist

Holding a bullhorn and standing in the flatbed of a truck pumping music alongside the protesters, Flores led chants in English and Spanish. Cars driving by honked in support. One driver waved a white handkerchief outside his window; another stuck out a fist in solidarity as the marchers cheered. Flores spotted a fellow environmental organizer in the crowd. “Shout out to Sierra Club — I see you!” she called out.

Flores stopped in front of City Hall and called up Ben Reynoso, a young activist running for city council. “As a kid, I woke up in the morning, and I looked at the mountains, and I loved it,” Reynoso told the crowd. “Now I wake up — and I live next to it — and I can’t even see it. That’s an issue.”

For environmental health advocates, taking part in a protest that unites disparate communities in the Inland Empire represents a new level of political will. But it still might not be enough. Local organizers say it seems impossible to keep up with all the newly proposed warehouse projects in the county, comparing it to an exhausting game of whack-a-mole. And as Flores put it, “A warehouse is a magnet for diesel emissions.”

So rather than rely solely on protests and grassroots campaigns, activists like Anna Sanchez are increasingly turning to legal and policy solutions — rules and regulations that will hold existing facilities and new e-commerce projects accountable.

Last year, environmental groups successfully persuaded the South Coast Air Quality Management District, the agency that monitors air pollution across Southern California, to create new rules that would make warehouses, sea and air ports, and railyards responsible for the emissions they bring into communities. Environmental groups across the region are now working with the agency to craft similar rules for mobile sources of pollution like diesel trucks, which contribute to 80 percent of local smog-forming nitrogen oxide emissions. They want stringent regulations on facilities that butt up against homes and schools.

The East Gate Air Cargo Logistics Center is one such project. It’s slated to be built just blocks away from residential neighborhoods like the one Sanchez lived in when she became pregnant with Nathan. Her father still owns that home, which is about a mile away from the project, and she’s adamant that another young family not suffer from breathing the air nearby.

Sanchez keeps a scrapbook of photos from when Nathan was a newborn so that he will know his story as he grows up. For the first year after he was born, he was in and out of the hospital with patches of his hair shaved so that doctors could run an IV through the veins in his scalp. Looking at the photos together, Sanchez asks her son for his reaction. Nathan pauses for a moment. “It’s scary,” he tells his mom.

Anna Sanchez shows her son Nathan one of his baby photos. Nathan’s being born with a birth defect linked to air pollution is the motivating force behind Sanchez’s decision to study environmental law. Justine Calma / Grist

He’s healthy now, though Sanchez occasionally must explain his abdominal scars and missing belly button to concerned teachers and classmates. His hair now falls below his shoulders. Sanchez had him grow it out to hide the shaved IV patches from his early years, and now she can’t bring herself to cut it. It’s a symbol of his health. “That’s your hair, buddy,” she said. “You did it.”

“He’s just full of life,” Sanchez said, swelling with pride. “We went through this journey together.”