California Attorney General Xavier Becerra announced today that his agency is suing the Federal Aviation Administration, the San Bernardino International Airport Authority, and the developer of an air cargo facility for unlawfully approving a controversial airport expansion without adequate environmental analysis. The nearly 700,000 square-foot warehouse, which is already under construction, is projected to generate at least 500 truck trips and 26 flights daily — and it’s right next door to a community that California’s Air Resources Board has already classified as disproportionately burdened by pollution.

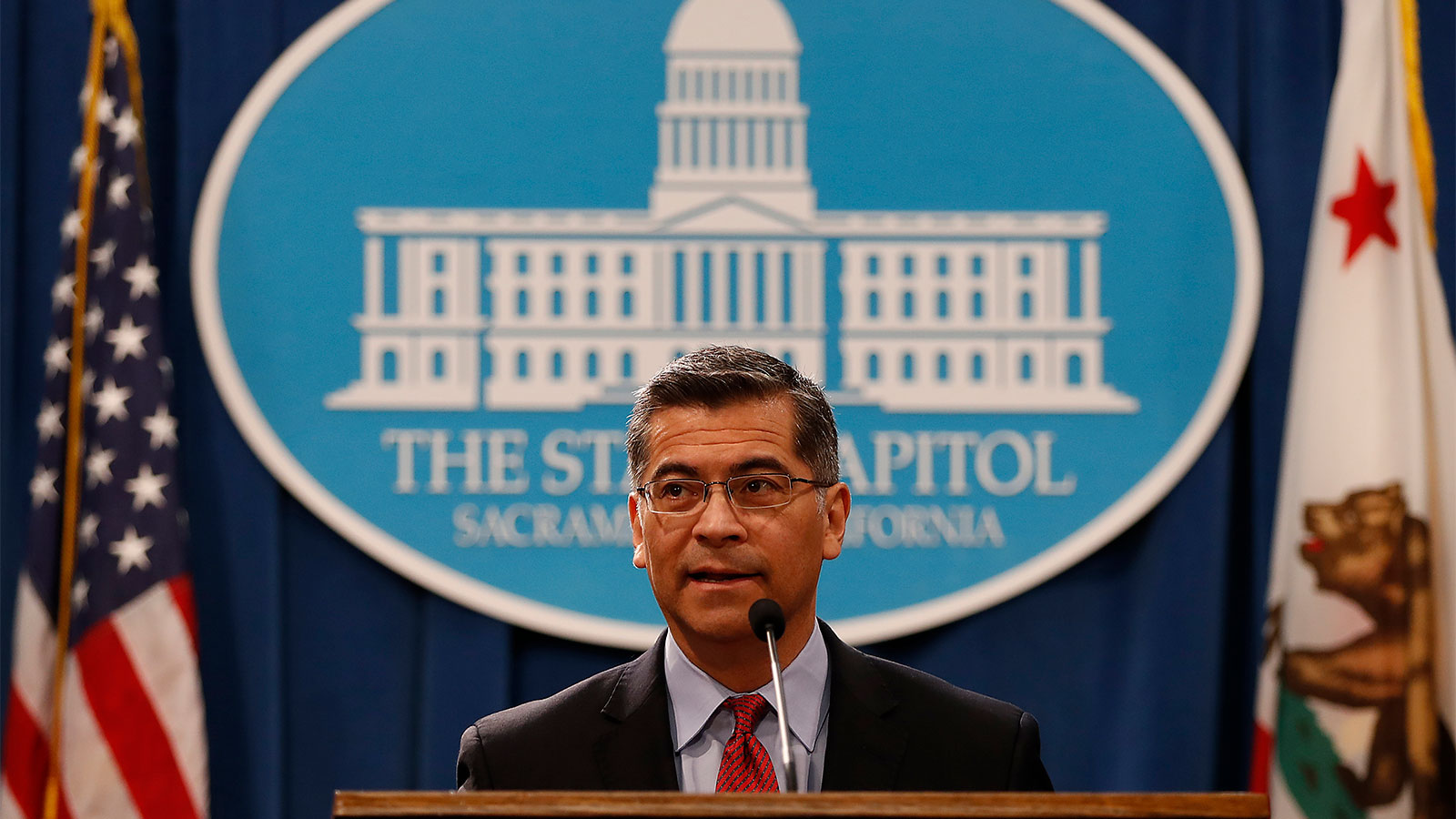

“In California we can’t have business-as-usual hurt distressed communities in our state,” said Becerra at a press conference at Indian Springs High School in San Bernardino on Friday morning. “We have a responsibility to provide justice, including environmental justice, to all of California’s communities.”

The lawsuit comes on the eve of the second anniversary of the creation of California’s Bureau of Environmental Justice. Two years ago, Becerra housed the bureau within the state Department of Justice’s environment section and gave it a singular focus: enforcing environmental laws to protect communities disproportionately burdened by pollution and contamination. Today’s suit is just the latest in a string of actions the bureau has taken to achieve this goal across the state in recent years — and one of relatively few that has taken the form of a formal legal intervention.

This is not the first time that the bureau has weighed in on the proposal to build an air cargo facility at the San Bernardino International Airport. While the Federal Aviation Administration conducted an environmental assessment of the proposed development last November, Becerra’s bureau submitted comments to the FAA and the San Bernardino airport authority urging that they perform a more rigorous environmental analysis and prepare a more thorough environmental impact statement.

Nevertheless, the FAA ultimately concluded that the proposed facility will have “no significant impact” and approved the airport expansion in December — despite its own projection that the development could generate one ton of toxic air pollution daily in a region already ranked as the worst in the nation for ozone pollution. In January, residents and community advocates sued, asking the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit to dismiss the FAA’s December decision on the grounds that the assessment doesn’t fulfill the requirements of federal environmental law.

“This case is perfectly illustrative of why you need an environmental justice bureau in the state attorney general’s office,” said Adrian Martinez, a staff attorney with Earthjustice, which filed the lawsuit in January against the FAA on behalf of the Center for Community Action and Environmental Justice and the Sierra Club. “It’s these types of cases where you really get a benefit from having the state weigh in and help environmental justice causes.”

Seeking justice outside of court

The environmental justice bureau, a unique and possibly first-of-its-kind unit within a state department of justice, was originally launched on February 22, 2018, with four of the department’s attorneys devoted to its work full-time. Today the bureau has six attorneys with a wide range of responsibilities, including reducing residential exposure to environmental toxins, challenging efforts by the federal government to roll back environmental protections, and holding industrial facilities accountable for polluting air, water, and land in California communities.

Grassroots advocates in some of the most polluted and contaminated communities across the state say that the bureau is changing the dynamics around how and if new industrial developments move forward — as well as protecting these communities from polluters by enforcing existing laws and providing a larger microphone for residents’ concerns.

By focusing closely on disparities like the large number of polluting facilities sited near low-income neighborhoods and communities of color, the bureau’s work has been game-changing, said Chelsea Tu, a senior attorney with the California-based Center on Race, Poverty, and the Environment, which provides legal, organizing, and technical aid to grassroots organizations fighting for a clean environment. “Having state backing and support highlights issues that otherwise we’re just fighting for on the ground,” said Tu. “Their support really lends that extra weight.”

In some cases the bureau has lent this extra weight by filing public letters alerting local agencies to potential violations of the California Environmental Quality Act, the state’s landmark law that requires state and local government agencies to determine the potential environmental impacts of proposed projects, inform decision makers and the public, and reduce those impacts. Last April, the bureau warned the city of Carson against approving land use permits for a chemical storage facility without first conducting a comprehensive environmental review to analyze and mitigate risks to residents. The facility had previously been granted the permits for more than four years prior to the bureau’s intervention.

In other cases the bureau has intervened through the courts, including in 2018 against the city of Fresno, which had approved a large industrial warehouse without a substantive environmental review — in violation of state law, according to Becerra’s office. The city and developer subsequently complied. In most cases, however, the bureau has done its job without having to take polluters or violators to court. Instead, the bureau has collaborated with local government agencies to ensure that they are fulfilling their responsibilities under the state’s environmental laws, Attorney General Becerra told Grist.

“The result is that we’ve been able to get a lot of change — not by having to sue, but by working with the local governments, pointing out their deficiencies, and saying, ‘We hate to sue, but if you keep going on this course, that’s probably where we’re headed,’” said Becerra. “And we’ve been able to have some good outcomes.”

An oil well near the town of Arvin, southeast of Bakersfield, California. David McNew / Getty Images

In Arvin, a city in California’s Central Valley, residents had battled for five years to more strictly regulate local oil and gas activity when the bureau weighed in, submitting a 2018 letter supporting a proposed city ordinance to impose more stringent requirements on petroleum facilities. The ordinance was approved shortly after the bureau’s intervention, replacing a more lax ordinance that was more than 50 years old. Among other new requirements, it prohibits oil and gas sites in sensitive areas by establishing buffers near homes, schools, and hospitals.

The ordinance was a major victory for groups like the Center on Race, Poverty, and the Environment, which worked with Arvin residents and environmental justice advocates to pass the measure. The bureau’s intervention tipped the scales on a divisive issue in the heart of the state’s oil country, said Tu, the lawyer for CRPE.

“I think it’s important that they are providing additional resources,” Tu told Grist. “I don’t see the environmental justice bureau being our savior — I see that they are the added capacity that we need from the state.”

The bureau has also monitored rapidly developing industries, like the movement and storage of retail and e-commerce products. It has issued timely and helpful public comments and guidance on how municipalities can ensure compliance with the state’s environmental laws, said Andrea Vidaurre, a policy analyst with the Southern California-based Center for Community Action and Environmental Justice. For example, in areas where proposed industrial developments will abut residential neighborhoods, the bureau’s lawyers have weighed in, reminding cities about recommended setback standards intended to protect the health of nearby residents. With the logistics industry booming, it’s beyond the capacity of small community-based organizations like CCAEJ to track every new project, Vidaurre said.

Too often residents in these impacted communities say that the government ignores their needs and concerns. The bureau’s involvement has changed this dynamic, according to Vidaurre, and its work on the proposed air cargo facility at the San Bernardino International Airport exemplifies this. “Of course you want to live in a world where the concerns of communities are taken as the same authority as government agencies, but that doesn’t always happen,” she told Grist. “I think it’s very validating when we’re not just yelling out to the wind and saying ‘this is unjust’ — that we have the backing of the state as well.”

Oversight and guidance

The bureau has also stepped in to provide oversight and guidance to municipalities as they begin to implement California’s SB 1000 law, which went into effect in 2018 and requires cities and counties to identify disadvantaged communities within their jurisdiction, so they can address environmental justice in local government planning. Municipalities are supposed to engage the community as they determine how to incorporate this element into their general plans. But some local governments have not yet complied, according to CCAEJ’s Vidaurre. That’s where the bureau’s lawyers have stepped in: to counsel municipalities on what meaningful public engagement should look like, and steps they must take before they approve an environmental justice measure.

“There’s still what seems like a learning curve for a lot of the municipalities over what environmental justice is,” said Vidaurre, noting the bureau’s interventions have led to improved dialogue between her organization and municipalities in Southern California’s Inland Empire.

Working with municipalities to help them understand their legal responsibilities under California environmental law, particularly in rapidly developing regions, has ultimately been more effective than he initially imagined, said Becerra. Balancing residents’ desire for economic growth while at the same time protecting their health and environment is the attorney general’s aim for the bureau.

“Low-income, minority communities should not always be the first and worst hit by pollution and environmental degradation, simply because they don’t have the resources to fend for themselves,” said Becerra. “And in many respects I think when environmental justice communities talk about our environmental justice bureau, what they’re simply saying is we’re helping level the playing field.”

Environmental planning and policy expert Michael Méndez praised the bureau’s work, but he noted that, if existing state regulatory agencies were fully executing their duties, there would be no need for the bureau to step in and enforce the law in this way. “We can’t rely on this bureau to do all that work, and we still need to focus on the different regulatory agencies: the California Air Resources Board, the Department of Pesticide Regulation, the Department of Toxic Substances Control. That’s where the real enforcement should be taking place,” said Méndez, an assistant professor at the University of California, Irvine. While the bureau is a positive first step, its capacity is limited by its small size, said Méndez. He also noted that, without a specific mandate to fund its efforts in the future, the bureau may disappear under a different administration.

Given the environmental justice needs of communities throughout the state, Becerra said that the bureau could easily expand — and that he would work to find a way to secure funding for that growth. “I have no doubt that the environmental justice bureau has proven itself not just effective but worthy of growing big enough so that we can cover the state really well.”