All eyes were on Maricopa County, Arizona, earlier this month as election officials were counting every vote. But in the meantime, another group has been busy counting every tree.

Trees bring enormous benefits to the communities where they grow. For example, they scrub pollution out of the air and counter the urban heat island effect — in some cases lowering ambient air temperatures by up to 9 degrees F. Having trees nearby can potentially help homeowners save on energy bills and prevent excess mortality from heat waves.

However, these benefits are not equitably distributed among communities. Instead, racist housing policies like redlining have made trees abundant in wealthy, white neighborhoods, but scarce for poorer communities of color.

This Providence, Rhode Island, neighborhood received a low Tree Equity Score from American Forests. Eben Dente / American Forests

“A map of tree cover in virtually any city in America is also effectively a map of income and race,” said Jad Daley, president and CEO of the conservation nonprofit American Forests.

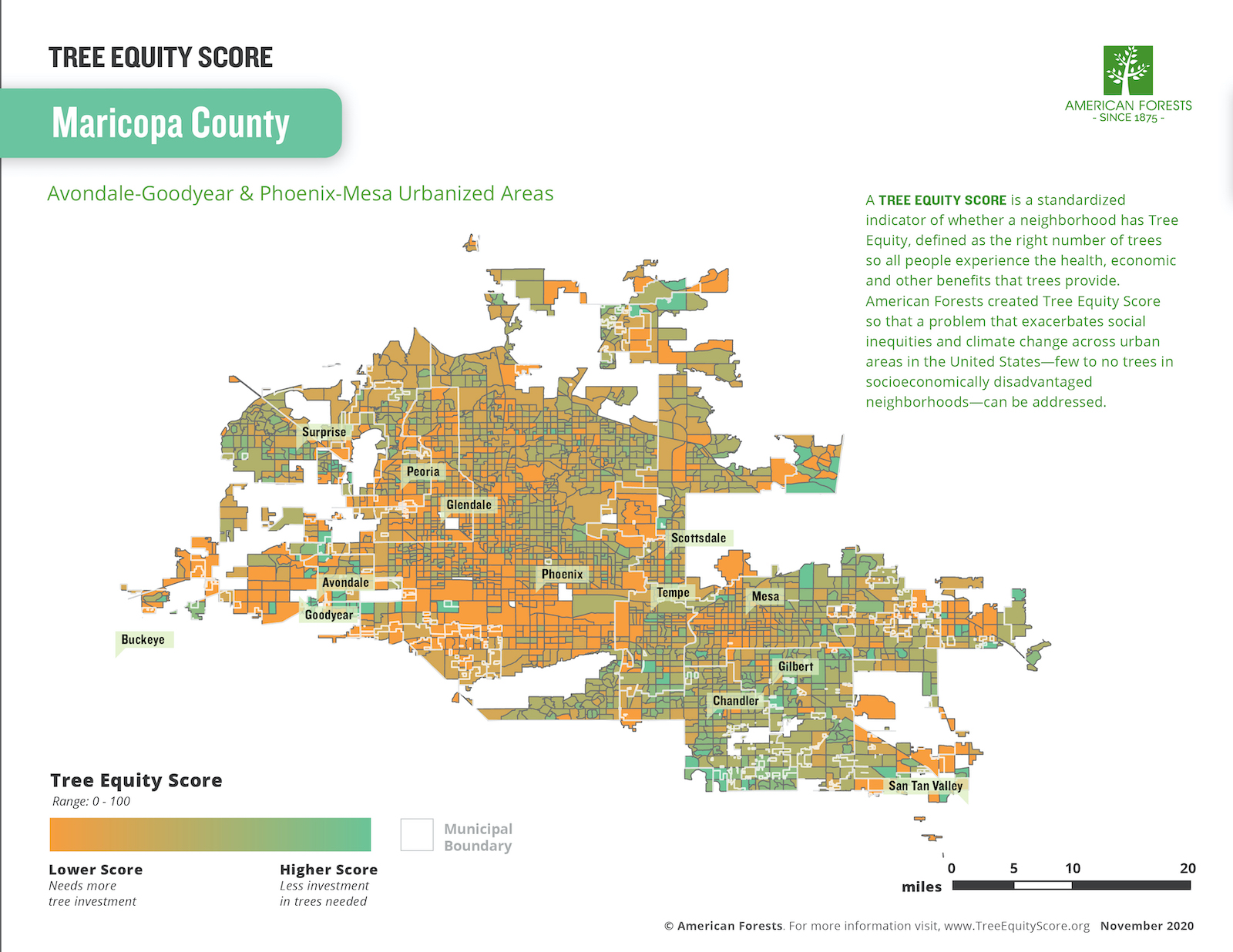

That’s why American Forests has been counting trees. As part of an effort unveiled on Tuesday to address nationwide inequities in tree cover, the group aims to assign “Tree Equity Scores” to cities and counties across the United States — beginning with three pilot sites, including Maricopa County. The equity scores take into account a number of factors, from population density to the unemployment rate, to determine which areas would benefit most from tree-planting efforts. American Forests hopes the project will help mitigate climate change, since trees suck carbon out of the atmosphere, while also combating systemic inequalities.

American Forests

“If your goal is health equity, if your goal is climate justice, this is a roadmap that is going to get you there,” said Jad Daley, American Forests’ president and CEO.

As defined by American Forests, neighborhoods achieve “Tree Equity” when they have enough canopy cover for residents to reap the health, economic, and other benefits that trees provide. To calculate progress toward this goal, American Forests begins by setting a target for each parcel of land — an ideal number of trees based on the natural environment and the area’s population density. Then, satellite data helps them figure out the “canopy gap,” the difference between the ideal number of trees and the number that is already there. Finally, they add information about race, age, income, unemployment, and temperature, creating a filter that highlights which neighborhoods policymakers should prioritize.

“It’s not just that cities need more trees,” Daley said. “They need trees in the right places.”

Currently, the organization has neighborhood-by-neighborhood Tree Equity Scores for three test regions: Maricopa County, the San Francisco Bay Area, and the state of Rhode Island. Daley said he hopes to expand the tool to all urbanized areas by 2022, covering land where 70 percent of the U.S. population lives.

Drone footage over Detroit, Michigan, shows disparities in tree cover. American Forests doesn’t have Tree Equity Scores for Michigan yet, but hopes to cover all urbanized areas by 2022.

The Tree Equity project may receive more attention thanks to the growing popularity of tree-planting projects. In August, the U.S. started the first chapter of the World Economic Forum’s 1 Trillion Trees Project, whose goal of planting a trillion trees by 2030 is supported by a whopping 90 percent of Americans. And Daley is optimistic about Vice President-elect Kamala Harris’ environmental justice record, as well as several federal bills to fund urban tree planning and create jobs in the sector.

Daley hopes the tools and information provided by the Tree Equity project can support what he called this “boom moment” for urban forestry projects, helping people to plant trees more thoughtfully and effectively. He also noted that tree equity presents an opportunity to attend to many of today’s most pressing issues, including racial injustice, a COVID-19 pandemic that has put thousands of people out of jobs, and an escalating climate crisis that Americans are increasingly worried about.

“Tree equity addresses climate change, jobs, COVID,” he said. “This is a perfect fit for this moment in time.”