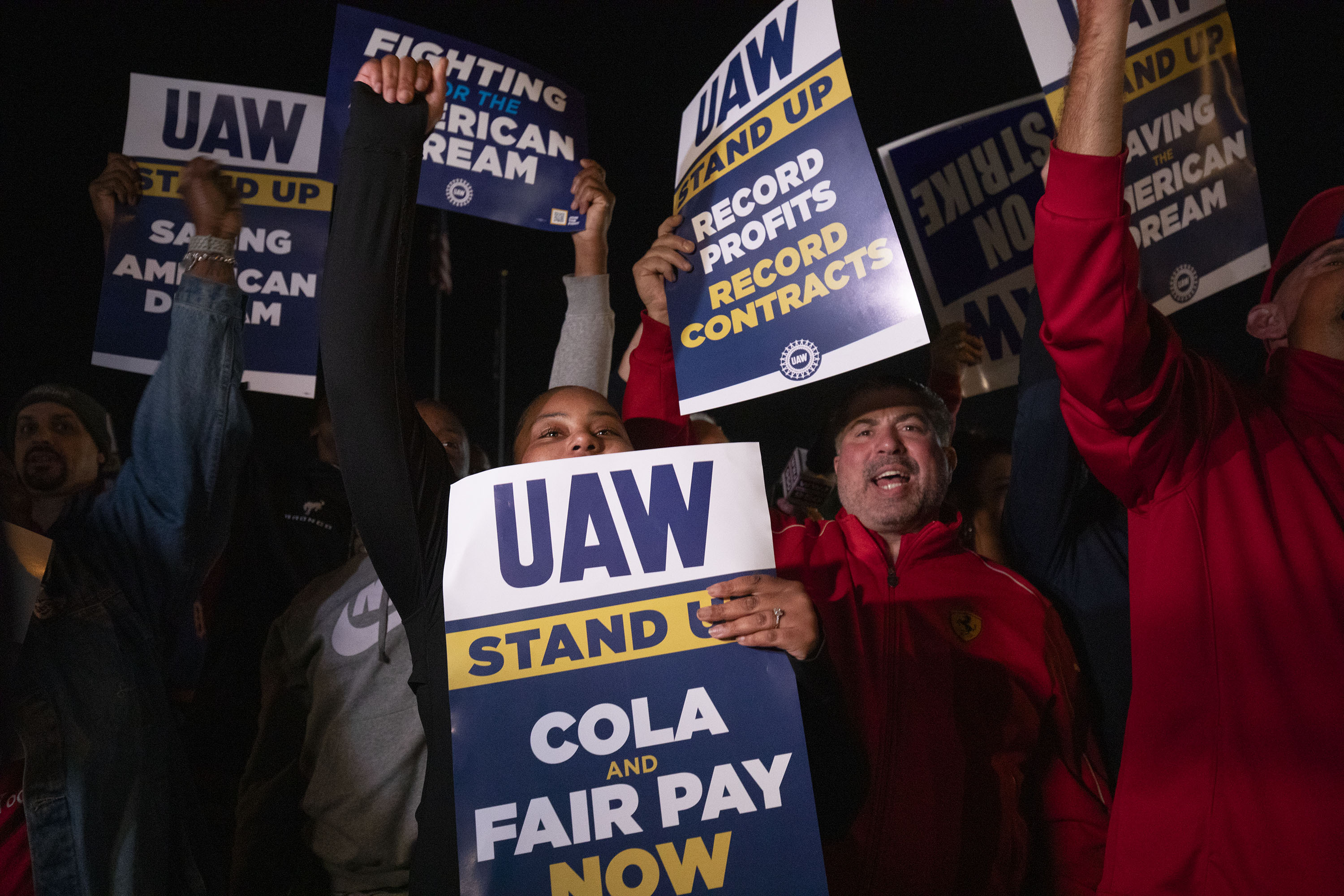

At the stroke of midnight on Friday, in three automotive factories across the Rust Belt, nightshift workers left their posts and poured out onto the streets to join whistling, cheering crowds. TV news footage from the night showed picketers intermingled with cars honking in support as R&B blared from sound systems on the sidewalks in front of the factory gates. For the first time in history, the United Auto Workers union, or UAW, initiated a strike targeting all of the Big Three automakers: Ford, General Motors, and Stellantis, which owns brands like Chrysler, Jeep, and Dodge.

The strike marks a breaking point after months of negotiations failed to result in a deal to renew the union’s contract with Big Three automakers, which expired on Friday. For now, the strike covers only 13,000 workers at a General Motors plant in Wentzville, Missouri; a Stellantis plant in Toledo, Ohio; and a Ford assembly plant in Wayne, Michigan. But the three closures could be just the beginning. UAW president Shawn Fain has warned that all 146,000 union workers are ready to strike at a moment’s notice. “If we need to go all out, we will,” said Fain Thursday night on Facebook Live. “Everything is on the table.”

If the work stoppage goes on for more than 10 days, analysts estimate it could cost automakers over $1 billion and hurt plans to push new electric vehicles onto the market.

EVs, and what they mean for the future of union labor in the automotive sector, loom large over the picket line. Automakers say meeting the union’s demands would threaten their ability to compete with nonunionized EV producers like Tesla, adding burdensome labor costs just as they’re making expensive investments in EVs. Workers, meanwhile, worry that billions in EV investments aren’t translating into good-paying, union jobs.

“It’s our job to organize,” Tony Totty, president of UAW Local 14 in Toledo, told Grist. “These corporations don’t want to share in our sweat equity with the profits we provide them.”

Collectively, the Big Three have committed to investing well over $100 billion in EV manufacturing over the next few years. The companies have also proposed 10 EV battery plants owned jointly with companies including South Korea-based LG Energy Solution and Samsung. Most new EV and battery plants are located in a growing “Battery Belt,” with Georgia, Kentucky, and Tennessee leading the charge alongside the traditional automotive heartlands of Michigan and Ohio. Many of those states have “right to work” laws that curtail collective bargaining, leading to lower union density and lower pay grades overall. Indeed, the vast majority of the Big Three’s proposed battery plants are nonunion.

To keep union membership strong, protect worker safety, and prevent the EV surge from undermining their bargaining power, the union has asked to include EV battery workers in their national contracts. “Now is really the moment, as the industry starts to take off, to ensure that those jobs can be union jobs,” J. Mijin Cha, an environmental studies professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz who studies labor issues and climate justice, told Grist.

Ford and Volkswagen have estimated that 30 percent less labor is required to build an EV compared to an internal combustion engine car, since EVs don’t require the complex parts needed to build engines and transmissions. Meanwhile, nonunion automakers like Tesla and Toyota are gaining an edge in the EV space, and offering substantially lower compensation than the Big Three. Ford has estimated the Big Three’s average hourly labor costs, including benefits, amount to around $65 per worker, compared to about $55 for foreign nonunion automakers in the U.S. like Toyota and Nissan. Tesla’s labor costs are even lower — at around $45 to $50 per worker per hour, according to industry analysts.

Autoworkers are watching this change with some trepidation, according to Marick Masters, a professor of management at Wayne State University who studies the auto industry and labor. “The shift to electrification both threatens jobs and it also threatens to establish another lower tier of wages in the industry,” he said. The UAW has so far had a string of organizing failures in the South, mostly associated with the region’s large number of foreign automakers, like Volkswagen and Nissan.

Totty, the Toledo-based UAW local president, has advocated heavily for union contracts at new battery plants. He personally welcomes the EV shift. His plant, Toledo Propulsion Systems, received $760 million in federal funding to transform it from a transmission plant into a plant that makes EV parts. Totty doesn’t believe it’ll take much extra training, or that anyone at the plant will lose their job. “We’re embracing it,” he said. What’s more concerning to him is the power and income imbalance between the people who do the backbreaking work at the plant, and the people who own it.

Among the UAW’s demands for its new contract is a 40 percent raise over the next four years, which it says is equal to the collective rise in CEO compensation at the Big Three over the past four years. The union has also asked for cost of living adjustments, the reinstatement of pensions, a 32-hour work week, and the elimination of a tiered wage system that pays newer employees less for the same work. So far, the three companies have countered with a 20 percent raise. As of Monday, the companies had not agreed to most of the union’s other demands.

In an interview with the New York Times, Ford CEO Jim Farley claimed that meeting UAW demands would prevent the company from investing in EVs. “We want to actually have a conversation about a sustainable future,” he told the Times, “not one that forces us to choose between going out of business and rewarding our workers.”

According to the union, the companies continue to make record-breaking profits, netting over $21 billion in just the first six months of 2023 and $250 billion over the last 10 years. Though the vast majority of those profits come from internal combustion engine cars, with EVs still a relatively small market, the auto companies are already tapping into billions of dollars in federal investments to electrify their fleets.

EVs are central to President Joe Biden’s climate agenda. Through the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act, the Biden administration has authorized nearly $100 billion in funding dedicated or available to support growth in the industry’s domestic supply chain. It’s part of Biden’s plan to, according to a recent Department of Energy EV funding announcement, “create not just more jobs but good jobs, Including union jobs.” More than $15 billion of that number is intended to support existing factories in the EV transition, in hopes of keeping manufacturing jobs in communities that rely on them. The administration has also made aggressive regulatory moves to push for EVs — under vehicle emissions standards released by the Environmental Protection Agency in April, EVs would need to make up two-thirds of all car sales in the U.S. by 2031.

Masters says that auto companies are responding to this pressure. “The companies,” he said, “are onboard, and their train has left the station. They’re going out of the internal combustion engine business.”

Some are calling the UAW strike the biggest labor crisis of the Biden presidency so far. The UAW has not yet endorsed Biden as a presidential candidate, citing inconsistencies between the administration’s push for EVs and its close ties with the labor movement. The union has previously criticized the president for lending billions to auto companies for EV manufacturing without requiring protections for union labor. UAW leaders have asked Biden to hold firm on his promises to deliver union jobs with clean energy investment, or else risk the energy transition exacerbating economic inequality.

The strike will continue, UAW has said, as long as parties fail to reach a consensus. Workers are organizing at Big Three factories across the country, preparing to shut them down if the moment calls for it. Experts say that a long-term strike could seriously hurt sales at the Big Three, possibly giving companies like Tesla a competitive edge.

“The UAW supports and is ready for the transition to a clean auto industry,” Fain said in a release. “But the EV transition must be a just transition that ensures auto workers have a place in the new economy.”