Ryan Mitchell lives and breathes tiny houses. He has been running the popular website The Tiny Life for the past five years; is currently planning a tiny house conference for approximately 120 people in Charlotte, N.C., where he lives; and has written a book on tiny living that’s due to be published in July. To top it off, he recently finished construction on a tiny house of his very own.

Mitchell’s dream, however, is a community of tiny houses. When asked what that would look like, he describes a grouping of mini-cottages around a large communal structure, which would include space to have shared meals, shows, and workshops. “The community aspect is actually a big part of what we [tiny house enthusiasts] like,” says Mitchell. With The Tiny Life, Mitchell has created an online forum of sorts for tiny house enthusiasts from all over the world. He wants to bring that community out of the virtual sphere and into the physical one.

How idyllic! But as Mitchell has learned firsthand, building a tiny house community from scratch is not as simple as it seems. Local building and zoning restrictions, not to mention securing startup money to buy land, are just a few of the obstacles to achieving a cottage-laden utopia.

Nevertheless, clusters of little huts in line with Mitchell’s vision are beginning to show their heads around the United States — though sprung from perhaps a different direction than he and the legions of tiny house followers might expect. In some areas of the country, a very small home isn’t just a model for the eco-conscious and design-inclined to pursue radical downsizing. Instead, it represents an opportunity for the homeless, mentally ill, and otherwise disenfranchised to get a toehold on upward mobility.

But regardless of origin, tiny house community acceptance faces yet another obstacle: the stigma that tends to surround groups of very small dwellings clustered on a single plot of land. Did somebody say “trailer park?”

The majority of tiny houses are, in fact, built on wheels. Due to common (and likely outdated) building codes, permanent dwellings often have minimum building requirements of around 800 square feet. To skirt the law, tiny dwellers build their houses using trailer bases as the foundation.

Most local zoning regulations prevent people from parking their tiny houses willy-nilly — there aren’t many homeowners who want to wake up one morning to find a tiny house at the bottom of their stoops, no matter how adorable. Tiny dwellers unwilling to purchase their own tract of land are then faced with a decision: tow your home onto the property of an owner who digs your digs, or pay rent to a trailer park, that most brushed-under-the-rug of American neighborhoods. In practice, the former tends to be the preferred option.

Alek Lisefski’s 160 square foot house in Sebastopol, Calif., currently lives in the backyard of a larger house.

Alek Lisefski’s tiny house sits behind a larger one. Lisefski, 31, is a web designer in Sebastopol, Calif. He and his girlfriend, Anjali Krystofiak, drove their 160 square-foot house from Iowa to California, where it’s now parked in someone else’s “big, beautiful backyard.” Lisefski and Krystofiak pay a small amount of rent to the property owner. Despite the relatively isolated placement of his house, Lisefski claims that tiny houses, by design, facilitate greater involvement with the community.

“The whole reasoning behind living in a tiny house is that it forces you to get rid of a good amount of your possessions,” he says. “[As a result, I’m] somewhat reliant on the community that I live in. For example, I don’t have a huge garage where I can store tools and the kind of stuff that people horde over decades of living in a house. So, if I need those things, I have to find a friend who has them or some sort of sharing program. It forces you to engage with other people rather than being shut up in your big comfy house.”

Alek LisefskiThe interior of Lisefski’s house, photographed from the loft bed.

Lisefski, like many tiny house dwellers, is quick to differentiate his home-on-wheels from an RV or trailer home. “Some people sort of fail to grasp that living in a house like this is the exact opposite of living in an RV,” he says. “It feels like a home. It’s built with nice materials that you’d find in a home.”

Jay Shafer might be the unofficial patron saint of tiny house living. Multiple tiny house dwellers interviewed for this story gushed over his artful, streamlined work — first with Tumbleweed Tiny House Company, and most recently with Four Lights Tiny House Company (both of which he founded). But even he has embraced the trailer home comparison — to a point. Shafer is currently in the process of developing a tiny house community in Sonoma County, Calif. He refers to his tiny village vision as “the most beautiful ‘trailer park’ in the world.” And yet his description of the future community, scheduled for completion in 2015, includes the following caveat:

There will be some rules established by the community to, presumably, keep anyone from turning their stereos up to eleven without earphones, conducting gang warfare on the streets, and/or barking incessantly all night-and-day [sic].

These presumably tongue-in-cheek (yet still cringeworthy) examples seem to reassure, more loudly than anything else, that the tiny house community movement is attempting to distance itself as much as possible from the “trailer trash” stereotype. In an interview with Fair Companies, Shafer made that desire for differentiation quite clear:

If we stick a more conventional RV in there between two [tiny] houses, it kind of messes up the whole composition. It won’t be really perceived as a trailer park — only by the zoning officials. Other than that, it’s a village of small houses.

To Alan Graham, founder of nonprofit Mobile Loaves and Fishes in Austin, Texas, the difference between a tiny house community and a trailer park is a moot point. “To set the record straight on the tiny house movement: It’s nothing new,” he says. “It’s actually existed for the entire advent of man living on the Earth. And in modern times, the recreational vehicle actually represents, in my mind, the greatest manifestation of the tiny home movement.”

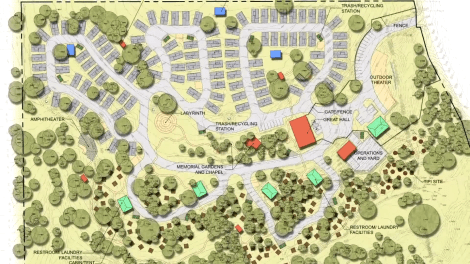

Tiny houses will coexist with RVs in the planned Community First! Village in Austin, Texas.

After raising $7 million in capital, Graham is preparing to break ground on Community First! Village, a 27-acre micro-home development for homeless and low-income individuals. For the past 10 years, Mobile Loaves & Fishes has helped the chronically homeless in Austin get back on their feet by helping them to acquire and move into RVs, on which they pay monthly rent to private RV parks.

Now, the organization has made plans and acquired the permits to build a development with 100 RVs and 135 tiny houses. Prototypes for the houses were designed by students at the University of Texas School of Architecture, and more will be developed by Texas A&M students. Energy efficiency, insulation, and protection against the Texas heat are crucial components of the design. The development will also include many communal features, including a three-acre community garden, an aquaponics pond, a chicken coop, a woodshop, and meeting spaces.

Mobile Loaves & FishesThe Community First! Village will cover 27 acres of land just outside of Austin.

The land for Community First! is located just outside the city limits of Austin, due to the city’s building code. According to Graham, urban building codes are the primary obstruction to tiny house communities ever gaining ground in cities: “[These communities are] not going to happen inside the corporate city limits of virtually any city in the United States of America. There are building code issues around the micro-home or the tiny home movement that our cities, our government, will have to overcome in order for this to really gain some strong legs.”

The city of Olympia, Wash., has, however, made changes to its own zoning laws to build a tiny house village. Quixote Village is one of the few full-time residential tiny house communities in the country. Unlike the target demographic for Shafer’s tonier tiny village, Quixote also happens to be a housing development for people in transition from homelessness.

Quixote Village in Olympia, Wash., is a tiny house community that opened on Christmas Eve 2013.

Jill Severn is on the board of directors of Panza, the nonprofit that helped establish Quixote Village, and showed me around the community one sunny Thursday.

“It’s interesting for me that for a lot of people who are talking about tiny houses, it’s about going from a big house to a small house,” she says. “And we’re coming from the opposite direction, which is going from no house to a tiny house.”

The village lies on just over two acres right on the Olympia city limits. It’s surrounded on three sides by industrial buildings, and the fourth side borders a little-used railroad and 25 acres of forested wetland. Thirty one-room, 144-square-foot cottages line the edges of the property in a horseshoe formation, facing inward toward a large community building that includes a double kitchen, showers, laundry facilities, and a common area with tables and couches. In fact, it looks a whole lot like Ryan Mitchell’s image of the perfect tiny house community.

The residents of Quixote Village all moved from a camp of tents, called Camp Quixote, which started in a downtown Olympia parking lot in 2007 as a protest against a city ordinance that forbade sitting or lying on sidewalks. Under threat of disbandment by the police, the camp was granted sanctuary on the grounds of the Olympia Unitarian Universalist Church, and moved from one church parking lot to another over the next six years. The organizations that hosted and supported the camp throughout that time created Panza, a nonprofit that raised money and public support to build the village, according to the vision of the Camp’s founders.

The village just opened on Christmas Eve, so there are parts of it that haven’t been completed, and its present aesthetic is fairly bare-bones. For example, almost as soon as I arrive, Severn points out the large stormwater ponds at the center of the property, which are admittedly unattractive. The houses themselves are well-built, but more utilitarian than something that might grace the pages of a shelter porn site.

Severn is planning on planting around the ponds to add some green to the landscape. There’s also a large space for a community garden, and each cottage has a yard about the size of a tablecloth where the residents are encouraged to plant flowers, vegetables, or anything else. The day I arrived, Severn was explaining to everyone we came across that she was in the process of buying a wheelbarrow for the village.

The village’s bike mechanic lives in this tiny house, which is more decorated than most of its neighbors.

Quixote Village is a clean and sober community by design. “The two big issues for people who have been homeless are mental illness and addiction, often [simultaneously,]” says Severn. “For months before we moved in here, the camp residents had a big discussion about wanting this to be a clean and sober community. And you need peer support to [overcome addiction.] For people with mental illness, isolation is the enemy.”

Severn tells me that the physical layout of the village has been ideal for the purposes of fostering a community: “It really is perfect. At one point, there was a suggestion of having the cottages in three or four little clusters. And everyone in camp said, ‘No, we do not want clusters, we’re all one community.’”

Quixote Village resident Robert Mitchell (standing) poses with Jill Severn (left, seated) and Jimi Christiansen (right, seated) on the porch of his house.

When it comes to the building and zoning obstacles that face many other tiny house communities, Severn acknowledges that the process was made much easier by the support of the larger Olympia community — and also by having all women county commissioners: “That was crucial – they instantly got the environmentally sustainable aspect of the village, as well as the need for community.”

The city did, however, have to pass a special zoning amendment to legalize the development.

“While we didn’t have any trouble with building codes, we did have to get the City of Olympia to pass a zoning code amendment to allow us to build what they called a ‘permanent homeless encampment’ on ‘property owned by the county in a light industrial zone,’” says Severn. “City staff folks were very helpful in crafting this change, and it passed the city council unanimously.”

Raúl Salazar, the village’s program manager, tells me that he’s gotten a lot of calls from all over the country expressing interest in replicating it. While he does see a future for tiny house communities, especially for homeless and low-income individuals, he acknowledges that Quixote Village is still a work in progress.

“I think the idea is, with something like this being so new, that we as an organization are really coming up with the structure,” he says. “Some of it we’ve come up with as we go, and we want to see how well it works before we make something else like this.”

Is this how the tiny house revolution has a chance at taking off — not with a bang, but with the blessing of local government? And is it more likely to follow stringent aesthetic policies, or will it be more accepting of all forms of micro-homes? These latter options are decidedly less exciting, but, as with all things unsexy, they might be more realistic. And as tiny houses are viewed less and less as the hermetic retreats of antisocial weirdos, and more as a viable basis for sustainable, community-driven living, it would seem to behoove cities interested in greening themselves to sit up and start paying attention.

Check back with us in the coming weeks to learn more about what cities are doing — and what they can do — to make tiny house communities a reality.