High-profile climate researchers, U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, and church officials will gather at the Vatican next week for a conference on climate change. It’s Pope Francis’s latest effort to raise the profile of the issue among churchgoers, and it’s sure to make some Catholics hot under the collar.

Since taking the helm of the church in 2013, Pope Francis has stated repeatedly that Christians have a moral obligation to lower carbon emissions. He has spoken frankly about how global warming hits poor, marginalized communities hardest. And he’s announced his intentions to issue, as early as June, a teaching document known as an encyclical which is set to merge the science and theology of climate change. He’s done these things in spite of angry rhetoric from conservative-leaning Catholics.

All this to say, dude has some guts. But are the pope’s actions doing more than just stirring up controversy in the church?

Here’s the thing. Leaders in the Catholic Church have spoken out about climate change before. In fact, previous popes and Catholic theologians have been talking about “honoring creation” (secular translation: not trashing the world) for centuries. Literally.

The best-known Catholic eco-crusader was the patron saint of animals and ecology and the father of barefoot bird-callers everywhere: Saint Francis of Assisi, famous for his work in the early 1200s. St. Francis was a bit of a radical, publicly protesting consumerism (in the buff, no less), campaigning for social justice, and writing extensively on caring for the environment. (The current pope, whose real name is Jorge Mario Bergoglio, takes his name from St. Francis.)

Jumping up to more recent times, Pope Benedict XVI, who held the office from 2005 to 2013, often spoke about the importance of making better use of natural resources, and how the deterioration of nature is connected with human culture. He never held a nude protest, but, hey, the guy still deserves a little credit for keeping the conversation going.

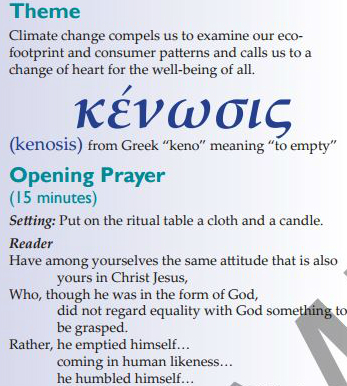

People on the lower rungs of the church hierarchy are speaking out about it, too. Sister Linda Haydock, the executive director of the Seattle-based Intercommunity Peace & Justice Center, has been trying to stir up interest in climate change in faith communities for years. Her organization’s mission is to address justice issues in the world and in the church. Among other things, it produces booklets that lay tough climate messages next to traditional, Catholic prayers.

A prayer from the IPJC booklet, “Climate Change: Our Call to Conversion.”Climate Change: Our Call to Conversion

I spoke with Haydock about changes she’s noticed in how people are responding to climate action. “We haven’t had leadership like this before, even in a local or regional way, on why we need to understand the issue of the environment, and climate chance in particular,” she said. “It’s all coming together. People are more ready to hear some of the messages on the environment than they were before.”

William Skylstad, the Bishop Emeritus of the Diocese of Spokane, Wash., agrees. “We’ve never seen such a change in caring about the climate than we have recently,” he told me. “More and more religious people are really concerned about how we impact our environment and how we are careful about our environment.”

Last year, Skylstad worked with a group of religious and indigenous leaders to modernize the Columbia River Treaty, which was originally signed in 1964 by the U.S. and Canada as an agreement to share the land for potential development and operation of dams. The call to “modernization” was really a call for restoration of the river, taking into consideration the indigenous tribes that live along the river, whose land has been damages by the dams.

The greening of the church has generated a backlash from some Catholics, of course. Some conservative Catholics say they’re miffed because: Francis is a mixing politics with religion, is a tree-hugging radical, and is probably ruining the economy, too. Or something. Here’s a taste of that viewpoint from Steve Moore, chief economist of the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank, via our friends at Fox News:

Pope Francis — and I say this as a Catholic — is a complete disaster when it comes to his public policy pronouncement. On the economy, and even more so on the environment, the pope has allied himself with the far left and has embraced an ideology that would make people poorer and less free.

But are these kind of complaints shutting down the pope? Uh, no. As loud as the far-right religious have been about their disapproval of the current climate-centric papacy, they’re in the minority. A Reuters poll found that Pope Francis’ call to see climate change as a moral obligation is actually leading more Christians to take action against climate change. Two-thirds of the respondents said that they believe world leaders are morally obligated to take action to reduce carbon emissions, and 72 percent said they were “personally morally obligated” to do what they can in their daily lives to reduce emissions.

Besides, Skylstad told me, disagreement between the religious is beside the point. As the pope focuses in on climate change, more of the world’s religious community is, too — and awareness is increasing because of it.

“I think you’re always going to find people who will disagree with certain elements,” Skylstad said. “For us, it’s an opportunity to educate and inform. Even if people might disagree, we’re looking at this like a long-form piece of education. You don’t put people in corners, you provide an opportunity for people to see things more accurately.”

So Pope Francis and countless others keep working for climate action, despite it being a controversial subject. The deniers can yell all they want. The pope and the global Catholic church, it seems, is refusing to give a damn.

Skylstad, an environment-reformer himself, put it best: “Talking about climate change makes some people nervous,” Skylstad said. “But that doesn’t mean we stop or don’t say anything about it.”

Preach.