The spotlight

There are few experiences more soul-sucking than sitting in traffic. According to NPR, the average American lost nearly an hour a week to traffic congestion in 2022. Drivers lose an additional 17 hours per year hunting for parking, USA Today reports — and in the same survey, 34 percent of U.S. drivers said they had given up on a trip because of parking problems.

By contrast: Picture living in a bustling neighborhood where all your friends, basic needs, and even your job are reachable by a quick walk or bike or bus ride. (Something many people experience, possibly for the first and last time, on college campuses.) In such a city, parking areas may have been reclaimed as urban greenways, chance encounters with neighbors might be more common, and small local businesses would proliferate and thrive.

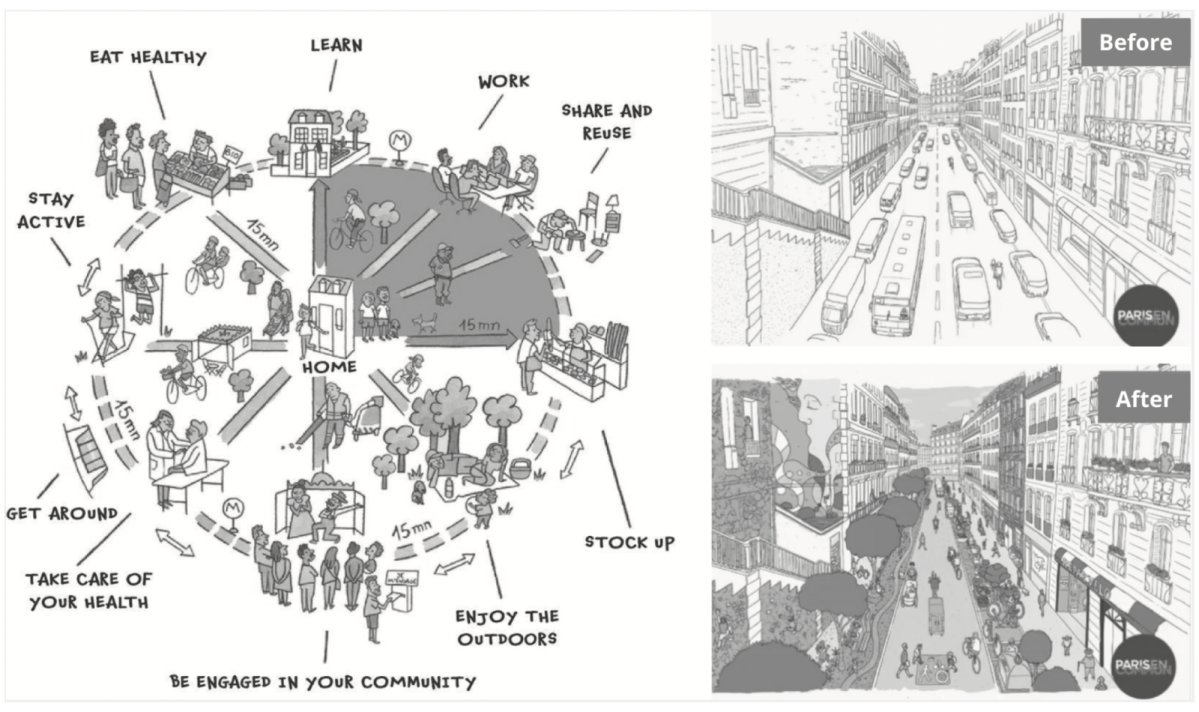

This vision is sometimes referred to as “the 15-minute city,” a concept pioneered by Franco-Colombian scientist and mathematician Carlos Moreno. It means basically what it sounds like: Instead of expecting residents to get in their cars and drive long distances to work, run errands, and take part in social activities, cities should instead be designed to provide those kinds of opportunities in close proximity to where people live, reducing overdependence on cars and increasing local social cohesion.

Paris, Moreno’s home, was the first city to put this concept into practice — part of a larger strategy to reduce air pollution and the presence of cars in the city’s iconic downtown areas. Since 2011, the French capital has reportedly reduced car traffic by 45 percent and associated nitrogen oxide pollution by 40 percent.

“We have been able to observe the concrete effects of proximity, density, social mix, and ubiquity on both residents’ quality of life and the vitality of neighborhoods,” Moreno writes in a new book, The 15-Minute City: A Solution to Saving Our Time and Our Planet, which published yesterday. In the book, his first to be published in English, Moreno chronicles the history of how cities came to be fragmented through zoning policies and highway construction, the origins of his 15-minute city concept, and how the idea is becoming a reality all over the world.

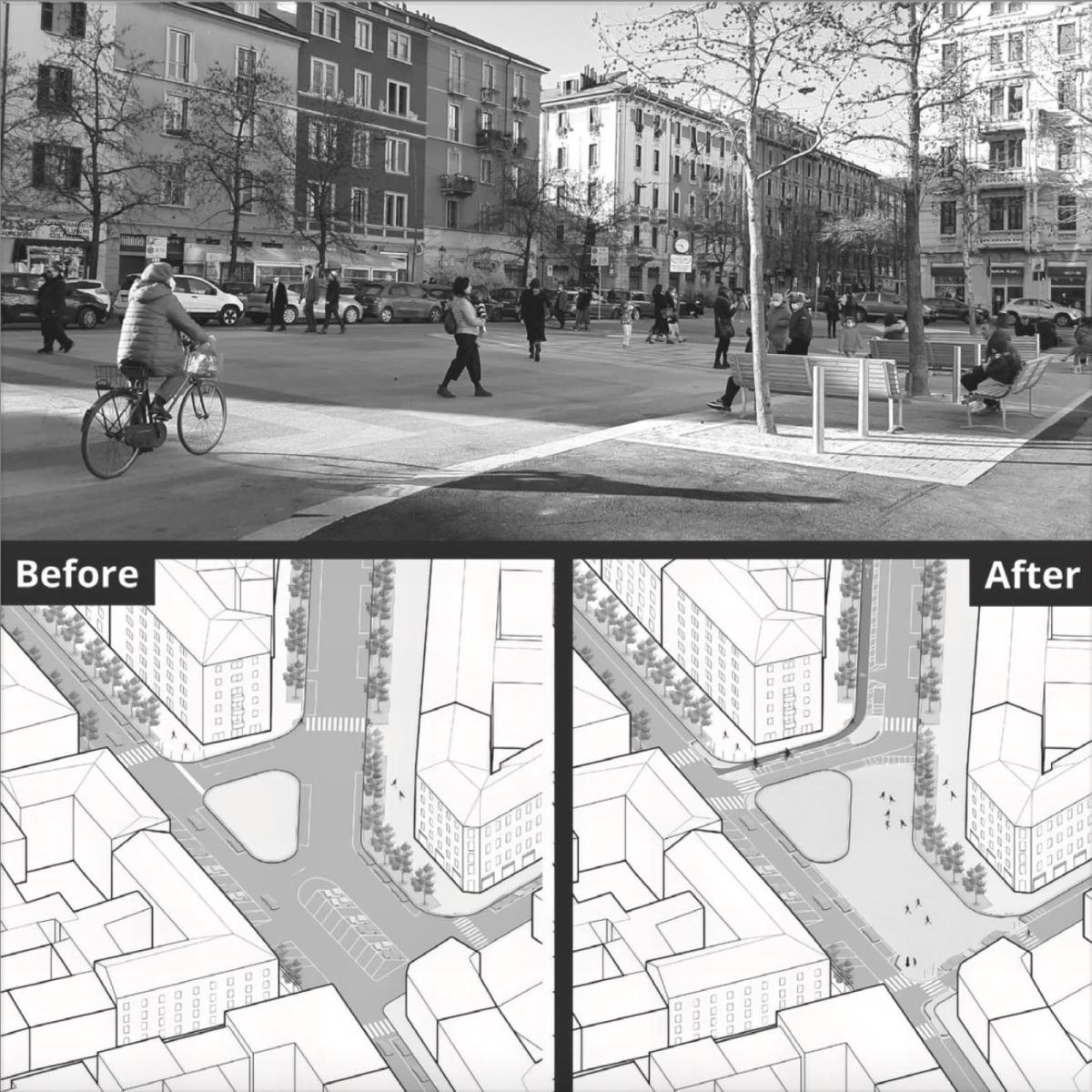

Before and after pictures from Moreno’s book show the transformation of Piazza Dergano in Milan. In 2018, the city reconfigured the space for residents to walk, gather, and play, instead of simply park their cars. Courtesy of Wiley

But, he told me, this book is not a manual for the right way to design a 15-minute city. Every local context is different.

In the U.S., fragmentation is often a direct result of redlining policies that served to racially segregate cities and hoard resources away from lower-income neighborhoods of color. Some critics point out that if urban planners don’t take those histories into account, and let communities lead revitalization efforts, then a concept like the 15-minute city could further exacerbate inequities. However, if it’s done right, the approach could help address those harmful legacies.

“It’s an invitation to reinvent our lifestyles and urban practices to build a better future, where sustainability, equity, and well-being are at the heart of our concerns,” Moreno writes in the book. I spoke with Moreno over Zoom and e-mail about the growth of the 15-minute city concept, some sources of backlash, and whom he hopes to reach with his new book. His responses have been edited and condensed for clarity.

![]()

Q. Tell me a bit about how you first got interested in cities and urban design.

A. Very good question. I’m not an architect or urbanist. I am a mathematician and computer scientist. I have developed a lot of different technologies for the intelligent control of complex systems. Just after the emergence of the internet, in the 2000s, I had a lot of requests from mayors for transforming lampposts, lights, doors, windows into smart equipment. I became one of the European leaders of the smart city.

In 2010, I decided to drop off smart technologies to examine a different way — the design of services in cities. I decided to continue to work in cities, but not from the technological angle, because technology is not enough for fighting against climate change, poverty, and social exclusion. We need to develop more local services. We need to develop more local jobs and to have more friendly neighborhoods and greener neighborhoods as well. And to reduce the role of individual cars, to reclaim the public space, to develop local commerce, to develop cultural activities.

I proposed this term “the human smart city” in 2012. And in 2015, the city of Paris hosted COP21, the big conference of countries for signing the Paris Agreement.

Anne Hidalgo was the mayor of Paris at this moment and, along with Mike Bloomberg, decided to convene mayors in parallel to COP21. With this amazing summit of mayors in Paris, cities said, “We are at the center of the problem — and we have the solutions. We need to change not only with technical measures, we need to change our lifestyle.” The cities signed an agreement [to support ambitious climate goals at the municipal level]. A few months after this, in October 2016, for the first time I proposed to cities to change this lifestyle through an ambitious urban plan for developing more local services. And I called that the 15-minute city.

Q. How have you seen the idea of the 15-minute city catch on in the past several years?

A. When I proposed this concept in 2016, a lot of people said, “Professor Moreno, this is a good idea, but this is a utopia.” The norm is to have long distances, long commutes. And maybe it is uncomfortable, but people at the end of the month have a wage, and they have the possibility for having a normal life.

As a researcher, I have experienced this concept in three districts in the east of Paris. I have observed that it is possible to change a city. The mayor of Paris [Anne Hidalgo] embraced this concept in 2019 for her re-election campaign. At that moment, we didn’t have a city with this concept implemented. Hidalgo took this concept in 2020, and she announced in June 2021 the big picture for five years in Paris. She proposed a concrete plan with different measures: local shops, local commerce, [safe] streets for kids, to ban cars in front of the schools, to open the schoolyards during the weekend. We have generated new districts: Clichy-Batignolles, La Félicité.

This is the growth of the 15-minute city inside of Paris. But at the same time, during COVID, the C40 Cities embraced this concept. The C40 is the global network of cities for fighting climate change.

We have, today, 293 cities in progress of implementing this concept. But not necessarily under the same name. In Utrecht, Netherlands, it’s the 10-minute city. In Dubai, the 20-minute city. In China, it’s the 15-minute circles of life. We have a lot of different nicknames, but the idea is the same: to develop a happy, polycentric, multiservice proximity. This is my motto.

Piazza Minniti, another square in Milan that was reclaimed for bikes, pedestrians, and play. Courtesy of Wiley

Q. I was also interested in your chapter on small towns. I think there’s a perception that the 15-minute city is only possible in already dense areas. How can small towns or rural areas adopt similar principles — and what are some of the different considerations?

A. The 15-minute city concept for urban areas is also the 30-minute territory for smaller towns and rural areas. It is also successful, although less well-known. Last weekend, I was at a conference in the south of France with small rural towns with less than 5,000 inhabitants, to talk and act in this direction.

In less densely populated areas, distances are generally greater and services less concentrated. The focus could be on efficient alternative methods of transport such as electric bikes, shuttle services, or car-sharing solutions to make travel more convenient without relying solely on the car. Using multifunctional spaces that can serve different purposes depending on the time of day — for example, a space that serves as a market in the morning, a café in the afternoon, and a meeting place in the evening — can be effective. Small towns and rural areas can also benefit from increased use of technology to access services such as telemedicine, online education, and digital government services, reducing the need for physical travel.

Q. I feel like I have to ask — the concept of the 15-minute city was seized on last year by right-wing conspiracy theorists, who painted it as a guise for government control and surveillance. Why do you think it’s been spun that way?

A. Yeah, this is a good question. At the same time, this was a hard period for me, for my wife, for my children. The first point, I think, that the conspiracy theorists have taken up, is efforts to reduce the role of the king car. To dare to attack the king car is, for the conspiracy mongers, an attack on individual freedom. I’m not in a war against cars, but we need to reduce the place of cars. The second point is related. The conspiracy mongers are climate skeptics, climate denialists. Today, scientists are a target of the denialists, because we said we have climate change, and this is irreversible. We have a lot of places with great risk if we continue to live with the same habits, if we continue to have this massive production and consumption.

The third point was about COVID. Because of COVID, we had this lockdown. When I proposed this question of proximity, the climate denialists, the anti-vaccine, the people that said that COVID-19 was a Chinese gun, considered that my idea was proposing a new lockdown. This is totally false, this is totally insane.

We have been living in very dark times. The dark face of humanity has become totally visible. The conspiracy mongers today are, today, with digital technologies, with fake news, with the bubble of false ideas, the denialists of science. I am just a scientist. But for climate denialists, we are the enemy, the scientists.

Q. Who would you say your intended audience for this book is?

A. This book is aimed at anyone interested in cities and ecosystems. It’s a book of work, knowledge, and deepening the concept, but it’s open to all disciplines because it’s written in a language that’s accessible to everyone. As I like to do, it also includes a lot of personal anecdotes, stories from my own life, and elements of the history of cities that even very erudite people don’t necessarily know.

My aim is threefold: to present the concept as it emerged, by looking back at the history of modern urbanism, looking in the rear-view mirror and learning from many thinkers and doers;

to explain it in detail, using the example of Paris, my city, which popularized it thanks to the commitment of Mayor Anne Hidalgo; and to go around the world, on five continents, with all kinds of examples to show that this concept does not depend on the size or density of places, nor on the political party or local governance — but that it is a humanist path for urban planning based on the quality of life of the inhabitants, faced with the ecological, economic, and social challenge for which it is urgent to change our way of life before it’s too late.

Q. What impact do you hope the book will have in the world?

A. I wrote this book as a bottle thrown into the sea in the image of my life. I wanted to offer the best of myself in a humanistic way, with a broad vision of our problems, without being dogmatic or sectarian about this or that. It is just a look at science, explaining the facts, making observations, and looking to the future, how we live and how we’d like to live differently.

I’ve been asked to register trademarks, patents, and licenses, create manuals, launch a competition. None of that interests me. A book is a profound part of yourself that you decide to share with everyone. It is written to reflect, not to proselytize. As a scientist, researcher, and teacher, I like to delve into the subject, to delve deeper, to pass on my knowledge with passion, commitment, and rigor, but without locking anyone into a single way of thinking.

— Claire Elise Thompson

More exposure

- Read: more about the 15-minute city and how, in the U.S., the suburbs might be a prime place for realizing the concept (The Washington Post)

- Read: a brief history of the hated commute, and how it’s continuing to evolve today (Bloomberg)

- Read: how the 15-minute city was embraced by a group of mayors all over the world as part of a COVID recovery plan (Grist)

- Listen: to a short segment about the 15-minute city, from NPR’s climate solutions week

- Watch: Carlos Moreno’s TED Talk, from 2021

- And read: Moreno’s new book, The 15-Minute City, which published yesterday

A parting shot

This infographic was first shared as part of a press conference that Moreno, Hidalgo, and Paris’ deputy mayor, Jean-Louis Missika, held in 2020. Moreno credits it with sparking international interest in the 15-minute city concept, noting that it has been shared, adapted, and translated into different languages all over the world. As he writes in his book: “It clearly and visually illustrates the 15-minute city’s concept, showing how essential services such as shops, schools, parks, and public transportation can be accessed nearby, making daily life easier for residents.”