The vision

It’s a friendly neighborhood contest. It provides dozens of fresh, nutritious loaves to the food pantry. Yeah, yeah. This year, you want to win.

It’s taken you weeks of practice to make half-decent bread out of HeatWheat2042 — the star variety from the mill this year. But you’ve tested and retested your latest recipe and … It. Is. Perfect.

“Are you done draining our kitchen battery now, you maniac?” your girlfriend asks. You only grin. Wiping sweat from your brow, you offer her a lightly buttered, warm slice of heaven.

“Oh, yeah,” she says, savoring her bite. “You’re going to win.”

— a drabble by Claire Elise Thompson

The spotlight

Throughout the pandemic, people have found comfort, stress relief, and a much needed sense of control by filling their kitchens with homemade bread and pastries. Home baking became such a craze during the lockdowns of 2020 that flour and yeast vanished from grocery store shelves.

The COVID-19 era likely won’t be the last time we’ll see upsets to our food system. Climate change poses a threat to the many-layered supply chain we rely on to bring us food — a supply chain that also depends heavily on fossil fuels, making it a major contributor to climate change. And it’s not just specialty crops that are at risk. Wheat yields could decrease by as much as 6 percent for every degree Celsius the planet warms. Globally, wheat accounts for 20 percent of the calories and protein that humans consume, so if we want a food-secure future, our daily bread is going to have to adapt.

It was that thought that drove former Grist chief of staff Caroline Saunders, now a pastry student at Le Cordon Bleu in Paris, to launch The Sustainable Baker podcast last fall. The show explores which essential, beloved ingredients are threatened by the changing climate, and how we can experiment with different types of baking to prepare — or even, to help avoid that unsavory future.

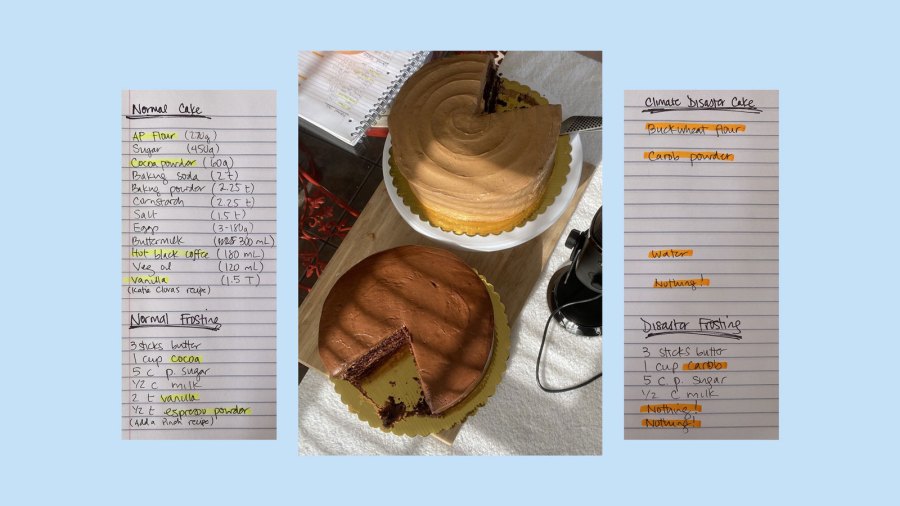

For the first episode, Saunders embarked on an experiment to bake a “climate disaster cake” — the kind of cake we might be eating in a few decades if the climate crisis disrupts the production of some of our favorite ingredients (which it likely will). She omitted vanilla and coffee, two climate-vulnerable crops that typically add depth and richness but aren’t essential to most cake recipes. She swapped cocoa for carob, and regular flour for buckwheat flour.

The reviews from her taste test weren’t encouraging. (They ranged from, “It tastes kind of like nothing,” to “a really moist couch cushion.”) But finding subtler ways of working in alternative ingredients has become a mainstay in Saunders’s baking. “I’m really a lot more interested than I used to be in diverse grains and weird, different varieties,” she says.

Going against the grain

For those of us baking at home, flour is a great place to start playing around with how our baking habits contribute to a more sustainable future.

Like most commercial crops in the world, common wheat, which accounts for 95 percent of the wheat grown globally, is an annual plant. Annuals typically require intensive inputs, and disrupt the soil every time they’re harvested and replanted. But there is an alternative: perennials.

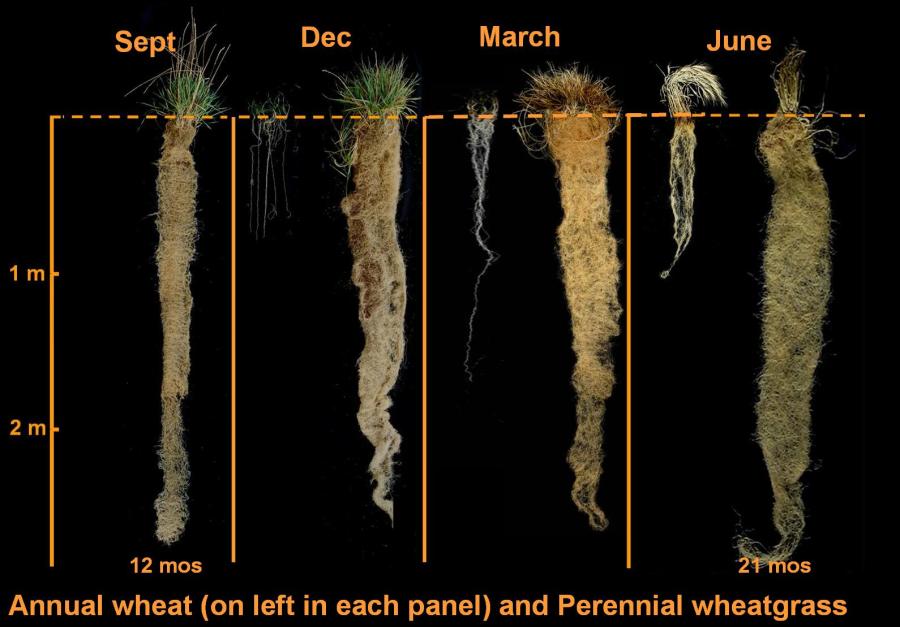

A perennial is a type of crop that stays in the ground year after year, instead of completing its life cycle with each harvest. Because they stay in place, perennials help to prevent erosion and enrich the soil with their deep, ever-growing root systems, which also allow them to reach deeper stores of water and nutrients.

One such grain is Kernza, the first perennial grain to become commercially available in the U.S. Developed by The Land Institute, an agricultural research organization in Kansas, Kernza comes from intermediate wheatgrass, which was brought to the U.S. about 100 years ago.

“Annual crops don’t function like an ecosystem,” Land Institute president Rachel Stroer told me last year. “They don’t steward the ecosystem in which they’re grown. We try to mimic the ecosystem with all kinds of subsidies. But perennial grasses are deeply rooted — and that’s exactly the characteristic that we’re trying to bring to the agriculture system.”

That characteristic may be necessary to sustain a growing population on a changing planet, Stroer believes.

In Saunders’s baking trials with Kernza, she’s found that it works best as part of a blend. “It almost smells nutty and spicy, so it goes really well if you make [something] like a cinnamon loaf with raisins,” she says. She suggests experimenting with Kernza or buckwheat — which, despite its name, is not actually related to wheat at all, and is naturally gluten-free — by replacing 10 to 25 percent of the flour in your go-to recipe.

Another way to broaden your flour repertoire is to look to local mills, which are often the ones experimenting with new, more adaptable grain varieties.

“If we talk about Cairnspring Mills, for instance,” — a Washington mill near where Saunders used to live — “they are growing varieties of wheat that were developed by the Washington State University Breadlab, right up the road in the Skagit Valley.” Some of the varieties being piloted there are regionally adapted to the Pacific Northwest, a rainier clime than common wheat prefers.

During lockdowns, when flour was scarce at grocery stores, local and regional mills saw sales increase by as much as 4,000 percent in some parts of the country. “What you started to see happen, as people found their way to regional mills to get flour, is that those smaller outfits were able to be more flexible and pivot and find these Band-Aid measures that the larger, longer, more brittle supply chains couldn’t,” Saunders says — measures like selling flour out of coffee bags, or selling a 50-pound bag to one neighborhood volunteer to divvy up into Ziplocs for the rest of the fam.

For Saunders, experimenting with sustainability in baking is an exciting part of our preparation for the uncertainty of a climate-changed future. “Cooking has always evolved. Baking has always evolved,” she says. “I think part of the challenge and joy of baking is the fact that it may change.”

Her advice: Try to embrace variability. “Bake like a bartender,” she says — a phrase given to her by a fellow baker. “It’ll be more delicious than the sum of its parts. Toss in a little something here, a little something there — that’s a great metaphor for baking in the era of climate change.”

More exposure

- Listen: The Sustainable Baker podcast covers more topics related to the future of bread and sweet treats

- Read: The Fate of Food by Amanda Little (another Grist alum!) explores what our tables will look like in a changed world

- Browse: writer and bread maven Amy Halloran’s running list of local mills throughout the U.S.

- Browse: a bunch of ways to use up sourdough discard, if you’re keeping a starter (FoodPrint)

- Bake: Saunders has a recipe for Kernza sourdough (adapted from Tartine Bakery’s country bread). Give it a whirl!

See for yourself

How do you think about climate resilience in the things you love to cook and bake? Reply to this email to tell us about new ingredients, recipes, or approaches you’ve tried — or send us a pic of your favorite creation!

Something else on your mind?

We want to hear your vision. Email us about the game-changing solution you’re working on or a topic you’d like to see this newsletter cover — or try your hand at writing your own 100-word drabble. Tell us what you see in our climate future (and maybe you’ll see it in the future of this newsletter).

On our horizon

- Join us for our next How We’re Fixin’ It event on Wednesday, February 16. Fix Network Weaver Tory Stephens will be talking with the leaders of HEET, a Cambridge nonprofit working to transform the electric grid with energy efficiency and geothermal micro districts. Register for the event here.

- If you haven’t yet read Fix’s What’s Next Issue, diving into the innovations and ideas poised to drive the conversation in 2022, there’s lots to explore. Check it out now.

A parting shot

Behold: a diagram showing the depth of perennial root networks compared with wimpy annual roots.