This story was originally published by the Guardian and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Sea levels could rise far more rapidly than expected in coming decades, according to new research that reveals Antarctica’s vast ice cap is less stable than previously thought.

The U.N.’s climate science body had predicted up to a meter of sea-level rise this century — but it did not anticipate any significant contribution from Antarctica, where increasing snowfall was expected to keep the ice sheet in balance.

According a study, published in the journal Nature, collapsing Antarctic ice sheets are expected to double sea-level rise to two meters by 2100, if carbon emissions are not cut.

Previously, only the passive melting of Antarctic ice by warmer air and seawater was considered but the new work added active processes, such as the disintegration of huge ice cliffs.

“This [doubling] could spell disaster for many low-lying cities,” said Robert DeConto, professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, who led the work. He said that if global warming was not halted, the rate of sea-level rise would change from millimeters per year to centimeters a year. “At that point it becomes about retreat [from cities], not engineering of defenses.”

As well as rising seas, climate change is also causing storms to become fiercer, forming a highly destructive combination for low-lying cities like New York, Mumbai, and Guangzhou. Many coastal cities are growing fast as populations rise and analysis by World Bank and OECD staff has shown that global flood damage could cost them $1 trillion a year by 2050 unless action is taken.

The cities most at risk in richer nations include Miami, Boston, and Nagoya, while cities in China, Vietnam, Bangladesh, and Ivory Coast are among those most in danger in less wealthy countries.

The new research follows other recent studies warning of the possibility of ice sheet collapse in Antarctica and suggesting huge sea-level rises. But the new work suggests that major rises are possible within the lifetimes of today’s children, not over centuries.

“The bad news is that in the business-as-usual, high-emissions scenario, we end up with very, very high estimates of the contribution of Antarctica to sea-level rise” by 2100, DeConto told the Guardian. But he said that if emissions were quickly slashed to zero, the rise in sea level from Antarctic ice could be reduced to almost nothing.

“This is the good news,” he said. “It is not too late and that is wonderful. But we can’t say we are 100 percent out of the woods.” Even if emissions are slashed, DeConto said, there remains a 10 percent chance that sea level will rise significantly.

David Vaughan, professor at the British Antarctic Survey and not part of the research team, said: “The new model includes for the first time a projection of how in future, the Antarctic ice sheet may to lose ice through processes that today we only see occurring in Greenland.

“I have no doubt that on a century to millennia timescale, warming will make these processes significant in Antarctica and drive a very significant Antarctic contribution to sea-level rise. The big question for me is, how soon could this all begin. I’m not sure, but these guys are definitely asking the right questions.”

Active physical processes are well-known ways of breaking up ice sheets but had not been included in complex 3D models of the Antarctic ice sheet before. The processes include water from melting on the surface of the ice sheet to flow down into crevasses and widen them further. “Meltwater can have a really deleterious effect,” said DeConto. “It’s an attack on the ice sheet from above as well as below.”

Today, he said, summer temperatures approach or just exceed freezing point around Antarctica: “It would not take much warming to see a pretty dramatic increase [in surface melting] and it would happen very quickly.”

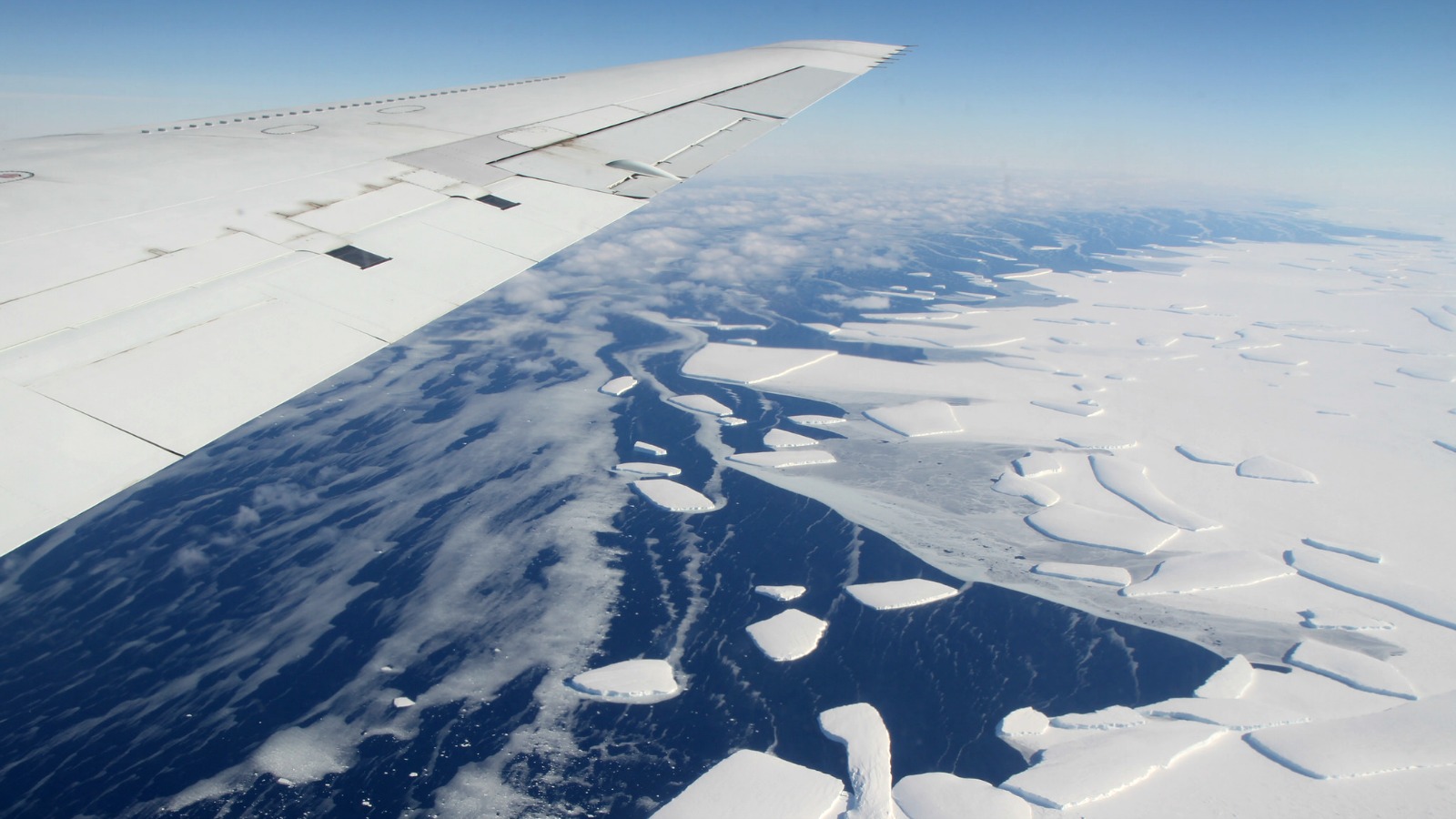

The new models also included the loss of floating ice shelves from the coast of Antarctica, which currently hold back the ice on land. The break-up of ice shelves can also leave huge ice cliffs 1,000 meters high towering over the ocean, which then collapse under their own weight, pushing up sea level even further.

The scientists calibrated their model against geological records of events 125,000 years ago and 3 million years ago, when the temperature was similar to today but sea level was much higher.

Sea-level rise is also driven by the expansion of water as it gets warmer, and in January, scientists suggested this factor had been significantly underestimated, adding further weight to concerns about future rises.

Recent temperatures have been shattering records and on Monday, it was announced that the Arctic ice cap had been reduced to its smallest winter area since records began in 1979, although the melting of this already floating sea ice does not push up ocean levels.