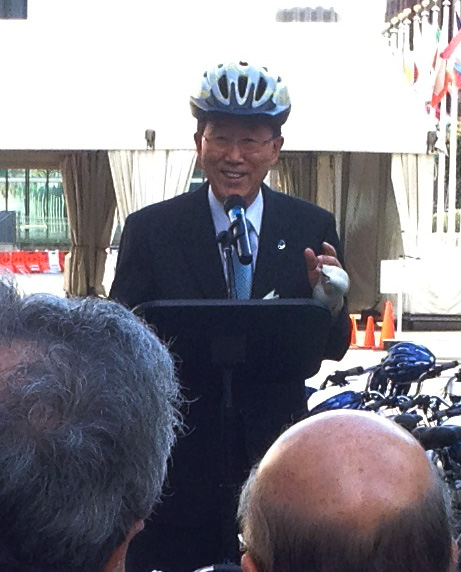

Secretary General Ban Ki-moon stood at a podium outside the U.N. on Friday wearing a dashing bike helmet — only to break my heart.

A promise had been made to me that I would get to ride bikes with the secretary general. To be fair, the promise was only implied; the invite from the Embassy of the Netherlands and its associated partners read only, “U.N. Bike Ride.” But I definitely was under the impression that the secretary general of the U.N. and I would very possibly be riding bikes simultaneously, in the same vicinity, in concert. Discussing issues of the day; inspiring others around us to celebrate the bike as a low-carbon — high-fun! — means of transport.

This is not me.

I hadn’t been to the U.N. before. People that live in New York don’t really go there. Only in New York City would an international organization tasked with keeping the world prosperous, healthy, and at peace be relegated to a strip of land by a murky river and then ignored. The complex sits like a once-great college campus at the end of 42nd Street, oozing stale optimism onto the highway that runs underneath it. It’s a symbol, not a destination — for this idea that we can all work together to change the world for the better despite a great deal of evidence to the contrary.

With the Earth Summit — or as it’s officially known, the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development (oh, bureaucracy) — now days away, we’re in one of our hopeful periods about the U.N., like we just bought a lottery ticket that probably won’t pay off but-what-if-this-one-time. Maybe this time, the U.N. will shift the world on its axis.

And how better to inaugurate that sentiment than a bike ride through New York City? A rainbow-colored coterie of diplomats and press and New Yorkers sweeping out from behind the high gates of the U.N. like Willy Wonka stepping into the public light, a show of solidarity revealing a magic that inspired the world. Or, at the very least, a visible statement of the utility and rationality of using bikes in America’s biggest city. I mean, it works in the Netherlands, and bike use is expanding in the U.S.

The very least I could do is join in.

What strikes you about events at the U.N. is how chummy the whole thing is. Everyone in the group gathered at the base of the famous thin blue tower last Friday seemed to know one another, all had the same credentials on lanyards around their necks, knew the speakers without introduction. I was an outsider, a New Yorker from the other side of the fence playing catchup. Without intending any disrespect, it was like meeting the homecoming court at a high school you don’t attend: a cozy clique with in-jokes and a hierarchy for which you can readily figure out the whos if not the whys.

The event began with a presentation, with speakers, as these things do. I missed one or two while pleading my case to security (I’d arrived after the credentialing office had closed) and straining to hear from my safe-enough distance away. But I arrived in time for the gifts. Ambassador Macharia Kamau of Kenya presented Secretary General Ban with a legitimately cool old bike taxi, a vehicle with thick tubing, brown paint, and a fringed platform on the back to carry things. New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg doesn’t attend such things, so he sent his ambassador, the city’s Commissioner of Transportation Janette Sadik-Khan. She offered the gift of future bikes, 10,000 scattered around the city as part of the recently-announced Citi Bike system, which will place rentable bikes throughout the city. (And by “the city,” I mean Manhattan and small parts of Brooklyn and Queens.) The master of ceremonies, Ambassador to the Netherlands H.E. Herman Schaper, presented the secretary general with an oversized bike bell in Dutch orange.

A bell is given.

When it was the secretary general’s turn to speak, he broke the bad news right up front. An undefined injury to his hand (his “steering wheel,” as he put it) meant that he wouldn’t be riding after all. The crowd seemed unfazed; I quashed my disappointment by recording the sad fact in my notebook followed by four exclamation points. He praised New York’s efforts to make “the city that never sleeps the city that always bikes,” and suggested that bikes would help transport the world to “a better tomorrow, a better future.” And with that, he was done.

The secretary general, his hand.

Ambassador Schaper came up to send the bike riders off, explaining that the route had been curtailed somewhat from their original vision. The NYPD (with its own rocky relationship with groups of bike riders) suggested that taking over multiple intersections during rush hour might be ill-advised. The route, then, would be in reserved lanes, from U.N. headquarters up to 50th Street. Some six blocks. At the end, the ambassador announced, there’d be a place to park your car. “Your car!” a man behind me guffawed.

To the bikes. I milled about making small talk as participants put on their helmets. Well, as some of them did; it didn’t seem to be required. The turnout was modest. An initial peloton of maybe 15 riders set out, with a few more handfuls following in bunches. I was among the last to leave, the large helmets having been appropriated by others with less large heads than my own.

By the time I exited the complex, it was not the inspiring scene I’d envisioned. I rode silently behind two others. The impression that we gave to the tourists standing around was probably less “Oh, I see that cycling is an effective, sensible way to get around the city,” and more “That tall guy on the bike appears to have a helmet that’s too small.”

When I arrived at the finish a few minutes later, nearly everyone was gone, retired to a reception at the residence of the Dutch ambassador. I asked two elderly women if they had any thoughts about the stand of empty bikes in the middle of their street, but they demurred. And that was it. Just me, standing on 50th Street, surrounded by bikes being loaded into a U-Haul truck.

Which is when it struck me that this exercise may not have been a rip-roaring success. If the goal was to light a fuse about bike transit that would explode in Rio, it was a dud. Shuttling bikes in the back of a large truck doesn’t exactly convey an Earth-friendly message, after all — nor does riding six blocks in a lane protected by the police suggest that biking is an effective way to get around the city. Having your most prominent representative show up unable to ride because of a minor injury is not helpful.

It was hot. I didn’t have a bike, and even if Citi Bike were already in place, the closest station to the U.N. would be several blocks away. So to get home I did what so many New Yorkers would do.

I hailed a cab.