danramarchSomeday the northern coast of Alaska could look like this.

This is a remarkable thing to consider:

“[T]he northern coast is about to become a real coast; maybe not today, maybe not this year, but in a short time. We need to start thinking about that.”

So says an authority no less than Major General Francis G. Mahon of the U.S. Northern Command. The comment came during a panel discussion this weekend in Washington, D.C.

“There are many, many others who have economic interests who would like to harvest [resources in the Arctic] and sell them on the economic market,” Mahon said.

Mahon said, as an example, that for Chinese exports to Europe, it is 40 percent shorter to move goods through the Bering Strait than to move those goods through Panama or around the southern tip of South America.

“From an economic standpoint, you know that will be exploited as quickly as possible,” Mahon said. “Ultimately, we will be operating up there more.”

We knew this, of course, and have written about it. But that frame, the creation of a new coast, is remarkable.

Think about the United States’ existing coasts. There’s the West Coast, with its long beaches and sporadic ports. There’s the Gulf Coast, clotted with refineries and tankers. The East Coast, with southern ports and massive cities. And now, in the mix, the North Coast.

The United States’ North Coast would be in Alaska. And Canada would have a bonanza of North Coast.

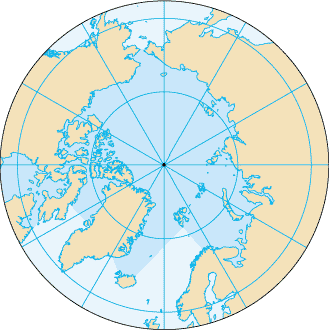

This is the North Pole. At upper left, Alaska and western Canada. At right, northern Russia. At bottom, northern Europe. Imagine the not-far-off future when the region is used for resource extraction (like offshore drilling or mines that were once blocked by piles of ice). And imagine that this ocean is ice-free for most of the year. Shipping from Alaska to Norway becomes trivial. From Russia to Canada. From resource-rich Greenland to any of these.

[protected-iframe id=”d5dfc69842d625da54b0d67f1776973b-5104299-30923557″ info=”https://maps.google.com/maps?gl=us&ie=UTF8&t=h&ll=73.428424,-126.738281&spn=18.246731,82.617188&z=3&output=embed” width=”470″ height=”350″]

The northern coast of Canada is already dotted with small settlements. Imagine the growth of massive ports, connected by railroad to airports or cities or other commercial infrastructure. Imagine the Hudson Bay ringed with city after city offshoring huge container ships and tankers. Imagine a “real coast,” the rush to build it out.

There’s a catch. Two catches, really. The first is that settlements near the Arctic Circle rely on permafrost. When permafrost thaws, buildings fall over and roads crumble. Arctic ice melt and permafrost thawing are happening in concert, and it’s unclear what the end result of the thaw will be. It’s possible that areas adjacent to the coast will be unsuitable for the sort of massive development a North Coast port would require.

Natural Resources CanadaSusceptibility of Canada’s North Coast to sea-level rise.

The second catch is that it would be hard to figure out where to build out ports. Container ships and other large vessels draw a lot of water, requiring dredged shipping lanes and certain water depths. But the melting Arctic ice will occur at the same time as significant rise in sea levels, which could potentially shift which areas are most suitable for shipping. It also means that all of the standard building-on-the-coast caveats apply.

All of this is deeply speculative; much of it is probably oddly optimistic. But imagine that there suddenly appeared a new, open ocean on the shores of Russia, Norway, Canada, and the United States, lined with mostly untouched coastline. That, in essence, is what is in the not-too-distant future for the world, a new ocean, unlocked from millennia of ice.

A new coast. New competition.