Twelve years ago, when Democrats controlled both houses of Congress and the presidency, the country teetered on the edge of passing its first-ever comprehensive climate bill. A triumvirate of senators were negotiating bipartisan legislation that would invest in clean energy, set a price on carbon pollution, and — as a carrot for Republicans — temporarily expand offshore drilling.

Then an oil rig — the Deepwater Horizon — exploded in the Gulf of Mexico. The loose bipartisan coalition collapsed. As President Barack Obama later wrote in his memoir, A Promised Land, “My already slim chances of passing climate legislation before the midterm elections had just gone up in smoke.”

Today, the sense of déjà vu is strong. The first half of 2022 has been stacked with events that have pushed climate change far down the list of priorities. The Biden administration has been caught between the war in Ukraine, surging inflation, the fight over Roe v. Wade, and, horrifically, continued gun violence. A month ago, many Democrats cited the Memorial Day recess as a loose deadline for having a climate reconciliation bill — one that could pass the Senate with only 50 votes — drafted or agreed upon. Any later, and the summer recesses and run-up to midterms could swallow any legislative opportunity. That date has now come and gone. “If you’re paying attention, you should be worried,” Jared Huffman, a Democratic representative from California, told E&E News last week.

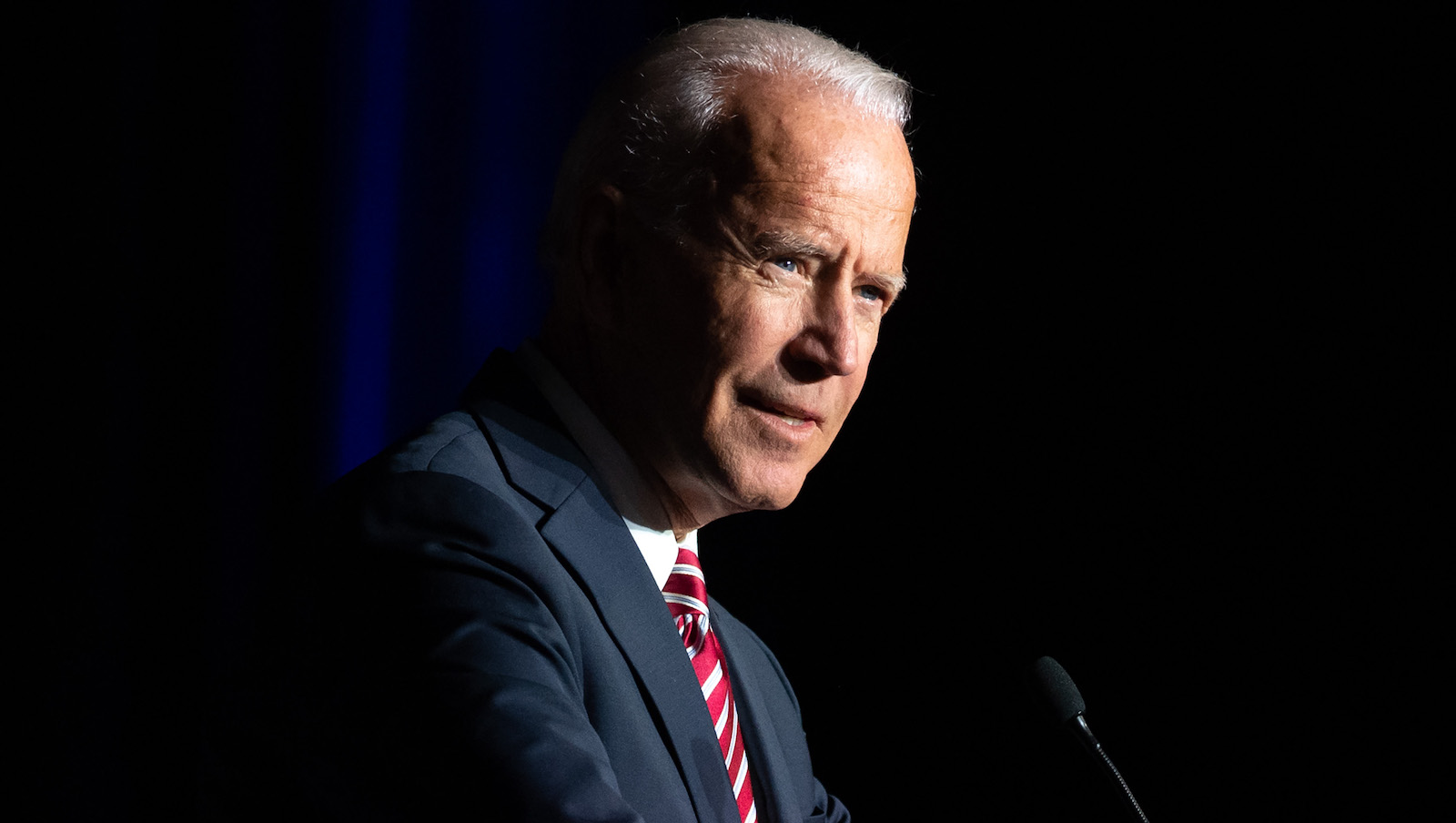

It’s both a sluggish and anticlimactic result for a party that, in 2020 and 2021, threw its weight behind climate action. The Build Back Better Act, President Biden’s massive $2 trillion spending framework, passed the House of Representatives last November, with $555 billion in spending for climate and clean energy. The bill would have invested in wind, solar, and geothermal power, offered Americans cash to buy EVs or e-bikes, retrofitted homes to be more energy efficient, and much, much more — but it died in the Senate, when Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia refused to support it.

Since then, climate action has virtually disappeared from the public and political agenda. Activists — who during the Trump administration seemed poised to transform U.S. politics — are tired and disillusioned. Meanwhile, in Congress, Manchin has arranged bipartisan energy talks and waffled on the importance of electric vehicles and even renewables.

In theory, some form of energy reconciliation package is still possible, one that would preserve some of the major green investments of Build Back Better. Josh Freed, the senior vice president for climate and energy at the Washington, D.C.-based think tank Third Way, gave the odds of passing something before the midterms at around 50 percent. “I don’t think that’s either optimistic or pessimistic,” he said. Democrats, he argued, are going to be under intense pressure — both to further their agenda and to have concrete action to show to voters in November. He compared the state of the bill to the Black Knight in Monty Python and the Holy Grail: “Everything’s cut off, but it’s not dead yet.”

Trevor Higgins, vice president for climate policy at the think tank Center for American Progress, similarly argued that there is still a chance for significant action, especially given that Manchin is currently in talks with Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer. “There’s just such a huge agreement across all the wings of the party on investments in clean energy,” he said. “It will come down to how Joe Manchin wants to proceed — but for the first time in a long while, his staff are in active negotiations to explore what it is that he actually wants.”

The timeline, however, will be tight. The deadline for passing a budget reconciliation bill is the end of the fiscal year, or the end of September. Between now and then, Congress has precious few working weeks to get legislation done. Given the Congressional recess in August, Freed estimates that Democrats will need to have a bill drafted and with sufficient support by late July. If not, he said, “there’s no way you can cram it all in for the last week of July and get it right.”

Chances are also slim that, come next year, Democrats will hold both the House and Senate. According to a 2021 analysis from the University of Virginia’s Center for Politics, the president’s party has, on average, lost 27 seats in the House and close to four seats in the Senate in midterm elections going back to 1946. With Democrats’ incredibly slim majority in the Senate, the loss of even a single seat could mean the end of climate legislation for another two years. Or four. Or even six.

It is hard to overstate the significance of the next few months. If Congress passes some version of the clean energy tax credits and investments in the Build Back Better Act, modelers at Princeton University estimate the United States would be within striking distance of Biden’s goal to halve emissions by 2030. Should Congress pass nothing at all, they estimate the country will emit an extra 5.2 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide over the next eight years. (Total global emissions were approximately 35 billion metric tons of CO2 in 2021.)

And yet, as drought takes over the West and heat waves rage across the nation, climate remains seemingly on the back burner. Part of that may be strategic; loudly protesting Manchin’s obstructionism has yielded no results, and the White House appears content to allow Schumer to take the lead on negotiations. But if there is no bill, the party that united around climate change will be forced to contend with what went wrong. The planet will be forced to contend with that, too.